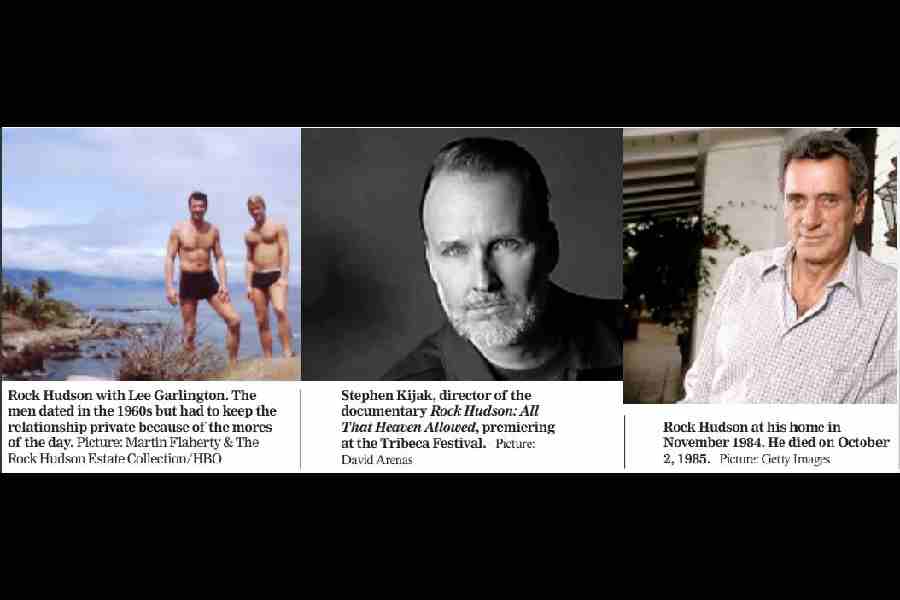

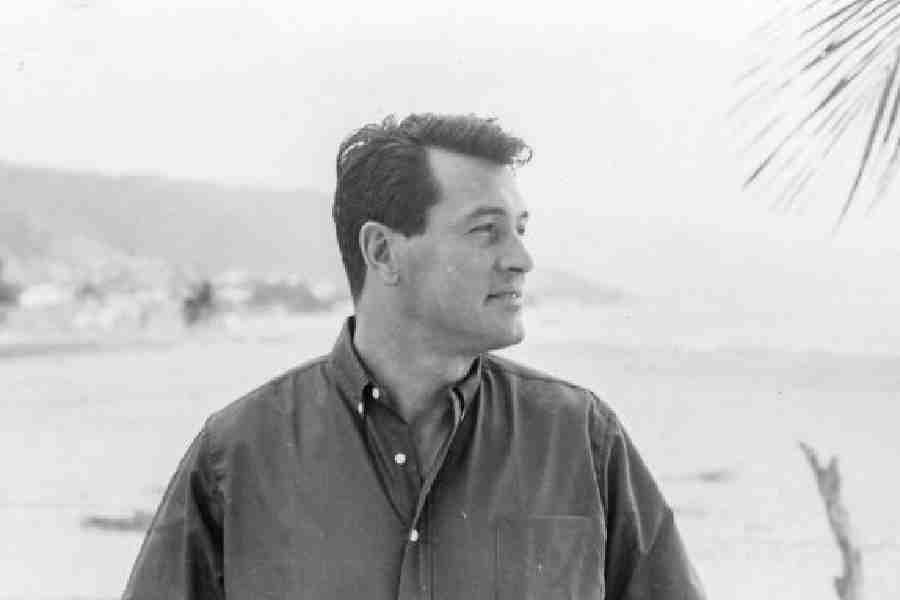

Rock Hudson was the ultimate midcentury movie star, turning heads and breaking hearts as the camera lit his chiselled face and rugged frame. The double life he led as a gay man — and his death from AIDS-related causes at 59 in 1985 — have sealed him in Hollywood lore, but he is largely unknown to new generations of film fans. For Stephen Kijak, the director of the HBO documentary Rock Hudson: All That Heaven Allowed, which premiered on Sunday at the Tribeca Festival, the actor was a fascinating figure to explore, both as a quintessential midcentury movie star and a gay icon. Kijak, who has directed several LGBTQ-themed films, spoke recently from his Los Angeles home about the legacy of and enduring fascination with a movie star who lived a gay life almost out in the open and who, in a true act of openness as one of the first celebrities — if not the first — to go public about his illness, changed the course of how the world responded to the AIDS epidemic.

What is it about Rock Hudson that drew you to do this film?

This film presented itself at exactly the right time, and from a group of people I love working with who brought me a subject I was fascinated by. I didn’t know a lot about Rock Hudson, and I love being in that spot. That journey of discovery is built into my process so that I can bring my audience along with me. It was initially titled The Accidental Activist, which is 100 per cent accurate but a little bit limiting. I thought there was a bigger story there, even though that is also an interesting element to his story: someone who doesn’t at all intend to change anything but inadvertently ends up being culturally, politically and socially a catalyst in a way that I think most people have completely forgotten about.

How did it go from being titled The Accidental Activist to All That Heaven Allowed?

There were so many more people over the course of the entire AIDS crisis who were true activists, who really moved the needle with forceful, direct action. I thought “activist,” and even “accidental,” might be a bit rich. There is so much more around his story: the Hollywood closet, the manufactured personality, the double life, the way the private existed weirdly under the surface of the manicured facade. He was having this kind of great rampant, randy gay sex life right there under everyone’s noses, but seemingly living without a care. There wasn’t the kind of angsty, oh-I-wish-Icould-just-be-an-out-gay-man. It was a generation that I don’t think considered that to be an option, or even something that they would want.

What do you think people who are not familiar with Rock Hudson will get from this film? He’s faded away. Who were the big marquee names from the ’50s who everybody knows?

It’s Marilyn Monroe. It’s James Dean. If anything, he is probably remembered for having died of AIDS in the ’80s and that scandal of having kissed Linda Evans on Dynasty when he was sick. Also, the manufactured star is not a concept that is completely alien to our modern age. He is a completely classic midcentury figure, from his upbringing, his trajectory, the look, the style, the movies he made. And who doesn’t like a doppelgänger story? The hall of mirrors, the split personality, the hidden life. There’s always the question of “why would young people be interested in this?” It wasn’t that long ago when it was really hard to be gay. Publicly, your life would be ruined. You were constantly afraid of being discovered.

Is there a sense of how a movie can hold something in this moment that it might not have held in the past? There are people who don’t know a subject and people who do.

So how is the method of our telling going to pull them both in and give them something that they didn’t expect or have experienced before? There is a slight tweak to how we approached who we were going to interview on film. Who you see on camera is a short stack of gay men who were in his life, either lovers, playmates, a wing man, a co-star, a best pal — people who he revealed himself to. What you get is an arc of gay men that takes you from pre-Stonewall, pre-gay liberation to the other side of the AIDS crisis. It’s Rock’s life that could have been through the lens of these guys.

Was that a specific decision?

Yes, and partly it was practical. We had to be very specific on how many days we could shoot. Granted, there is a part of me that wishes that we could have been rolling on Linda Evans when she tears up, but I think the choke in her voice still works. And you’re seeing her and him in their Dynasty glory days.

Does this movie represent more than just Rock Hudson?

Does it represent the film industry still regarding that “double life” idea? Well, I’m not going to name names, but you know there’s a handful of Rock Hudsons out there right now who have to be even more careful given the fact that everyone has a little camera in their phone. Confidential magazine was one thing, but it seems so quaint now looking back.

Do you think this film documents something people long to return to? The old Hollywood, maybe?

When his films were great, they were so great. The Douglas Sirk films were so lush and so layered. I could watch All That Heaven Allows a hundred times. Oh, and Written on the Wind with that crazy Dorothy Malone performance! Can I make a movie about her next?

The New York Times News Service