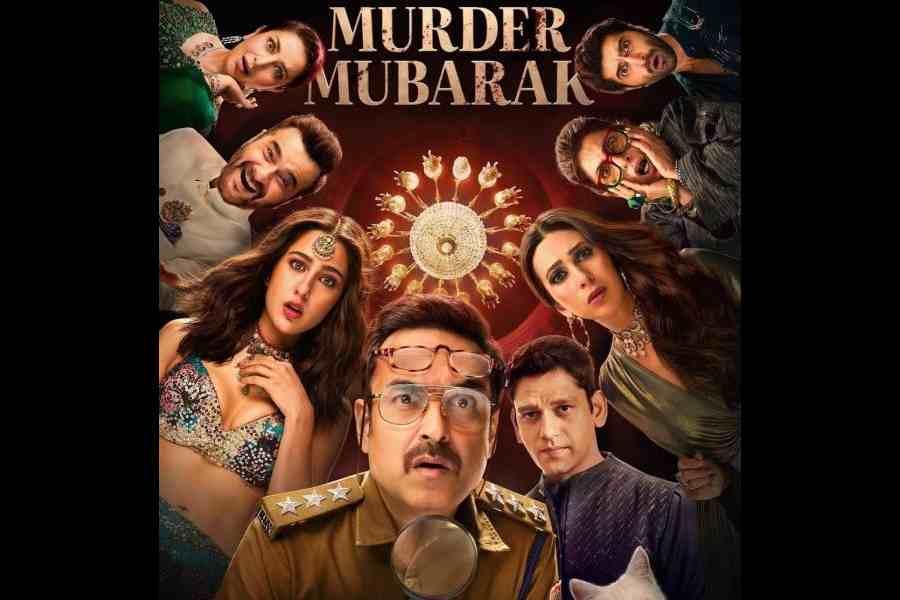

Murder Mubarak — a trippy whodunit featuring an ensemble cast comprising the likes of Sara Ali Khan, Vijay Varma, Pankaj Tripathi, Dimple Kapadia and Karisma Kapoor among others — streams on Netflix from March 15. t2 chatted with the film’s director Homi Adajania — the man behind films like Being Cyrus, Cocktail and Finding Fanny — to know more.

What sets Murder Mubarak apart from what you have made so far?

The USP is the uniqueness of the world that has been created as well as the ensemble cast that has come together. The vibe is quirky and is peppered with humour despite its dark theme. There is a nice freshness to it.

How does one make a murder mystery tight and thrilling when the source material, in this case, Anuja Chauhan’s Club You To Death, is already present in the public domain?

The film’s writers Suprotim (Sengupta) and Gazal (Dhaliwal) are the ones who have tweaked it. I can’t take any credit for it. When I was first offered the idea of doing this film by Dinesh Vijan (producer), I requested him to give me a bound script because I didn’t have the time or the headspace to work on the script. I was busy promoting Saas, Bahu Aur Flamingo at that time.

Working on a script like this is difficult. With a novel, you have the luxury of time, but in a film, you have to figure out what you keep and what to leave out.

It is a beautiful script. It is an out-and-out whodunit but it is also a love story. The writers did well in carving out the juicy parts from the book and using them in the script.

For me, what was unique was this world which I am pretty familiar with. I used to play rugby at the Bombay Gymkhana. It is a world I know inside out but they wanted it to be based in Delhi. But it isn’t about the elite in Delhi. It is like a subsect of this gymkhana elite who live in a microcosm. They consider that as the all-important world to the extent that they are almost desensitised to what is happening outside. And, strangely, it almost becomes a confederacy of dunces! (Laughs). The whole thing is quite amusing.

While researching the film, I took my team to hang out at these clubs and observe the traditions there. For the first time, I was sitting in a place which I was extremely familiar with but I was looking at it from an objective lens and I found some of the stuff so absurd... like this colonial hangover of practices and traditions and all that. It is a lot like the clubs in Calcutta. I used to go there to play rugby at CC&FC and Tolly (Club).

Irrespective of the plot, what do you feel are the elementary essentials of a murder mystery?

You need to leave breadcrumbs and clues for the audience and not try and hoodwink them. The script should be such that when the final reveal is made, the viewer should be able to follow the trail back and say: ‘Oh my God, it was always there, we just didn’t see it!’ That is an extremely effective tool. It is not about suddenly opening a card at the end... that is the easiest thing to do.

What is interesting in this film is that there are so many characters and they all have secrets they would kill for. Everyone is a player. One just needs to figure out who the big player is in the middle of it all. That is what we followed in this narrative.

In a murder mystery, you need to throw in red herrings. You make it obvious that one character is guilty and then pull out the googly, which makes the viewer say: ‘Okay, it couldn’t have been him/ her because they were somewhere else when this happened.’

But playing around with that gets quite convoluted and is difficult to keep a tab. I was shooting one day and I remember asking where one of the actors was. And then I was told that the character was dead! (Laughs) And suddenly I remembered that the character had died three scenes earlier!

What was it like directing this huge ensemble cast? It must have come with its own set of challenges...

I have done ensembles before. I did Finding Fanny which had a bunch of veteran actors too. It is difficult but it is great fun. When you have actors of a certain calibre, they start feeding off each other and upping their own game. That is a big plus with an ensemble cast.

The set-up on my set is very democratic and anyone with any kind of agenda wouldn’t belong there. It is tough sometimes when you have a lot of people in the frame because the viewer has one pair of eyes and can only look at one thing at a time. I don’t like to keep looking at the monitor when I am shooting. I like to feel what the actors are going through. But in this case, I had to be present at the monitor because I had to see what all the characters were doing in the same frame. When you have about seven actors in the same frame, you want to make sure everyone performs to their character.

Working with this ensemble was exciting for me because everyone was different and it sort of changed my game. In that case, there is no rule book that a director can follow. It has more to do with intuition and communicating with each person on a different wavelength. That is where the fun happens when you work with new people. But there is also an advantage of working with people you have worked with before. It works both ways.

Speaking of people you have worked with before, is it a given that Dimple Kapadia has to be a part of every Homi Adajania project?

What to do?

You sound almost helpless!

It is the cross I have to bear (laughs). It was just a coincidence that she was in the second film (Cocktail) after the first (Being Cyrus). Then it became a bit of a habit by the third (Finding Fanny). But then, having her on set is a boon. She is very good!

What is it about the sub-genre of having multiple suspects in a confined space that works so well for a murder mystery? We have seen that recently in the Knives Out films and also Kenneth Branagh’s adaptation of Agatha Christie’s novels...

I feel it gives the audience a higher sense of participation. They are a part of the ride, they also want to play detective. It keeps people way more engaged in a certain way. And with social media being around today, people will give theories and counter-theories and hence the level of engagement is high.

Honestly, I have never been able to wrap my head around the trope where the detective comes in at the end with all the suspects sitting there, which is exactly how it is in my film as well (laughs). Then, by the process of elimination, he proceeds to tell people that you have not done the murder, which is anyway something that both the detective and the suspect know. I don’t know why they don’t cut to the chase and say: ‘Hey, you are the murderer!’

But the genre thrives on this elimination and reduction kind of thing. So that the audience can also go through the play in their heads and say: ‘Okay, I thought this, but this character was doing it for this reason and therefore, he or she is not the murderer now.’

Close to two decades in the business, what kind of a headspace as a filmmaker are you in now?

I am not committed to any project right now. I am not in any kind of headspace but I am inclining towards comedy. But then again, my form of comedy is something that people find to be quite dark. Honestly, I am open to anything. The story has to resonate. It clicks and you say ‘yes’ and move on.

I have made a list of what I am going to do in the next five years because I suddenly realised I can’t jump off mountains in my late 50s... my knees will not be able to keep up. I don’t know what I am going to be working on after I finish all that.

So many years on, do you remember your first day on the set of Being Cyrus?

I was fearless. But I was fearless not because I was brave. I was fearless because I had nothing to lose. I was a diving instructor from Lakshadweep. Everyone, for some reason, thought I had made ad films, which I had never done. I was passionate about storytelling but I was technically zilch when it came to filmmaking.

There was a sort of naivete and fearlessness which I would tell that buffoon of so many years ago to have hung on to (laughs). I could have taken it along with me and it would have transformed into something else... it wouldn’t have been naivete anymore. It wouldn’t have been that kind of fearlessness, but it would have become a very strong weapon to have in my arsenal as an old man.