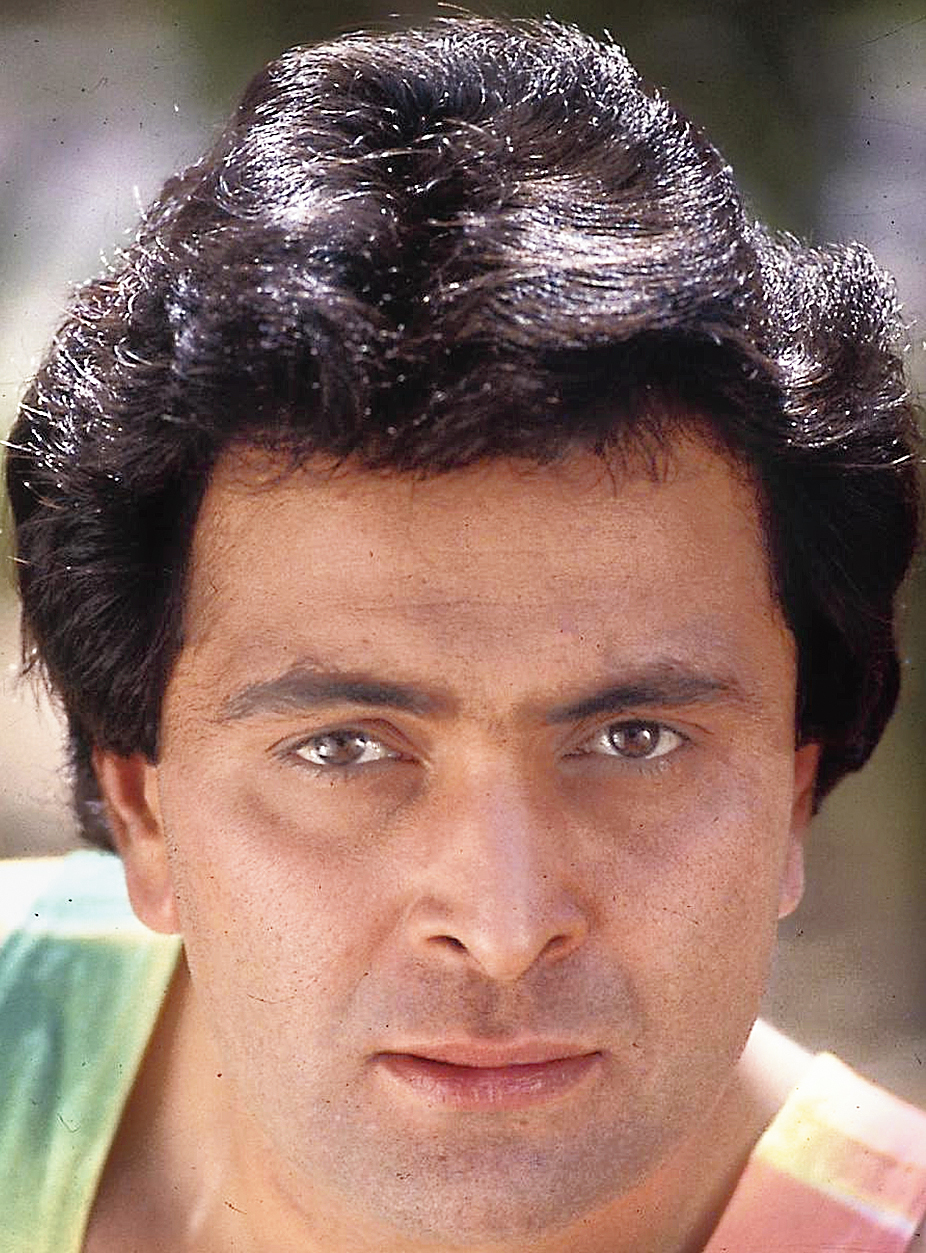

A blue-eyed, rosy-cheeked Kapoor scion, privileged from birth. A celebrity before his debut film was even released. A hero producers were waiting to snap up. His father was the famous Raj Kapoor and entry into the film industry came as a birthright.

A common man with bulging eyes, hardly the conventional hero. Couldn’t afford the travel expenses to become a cricketer. An uncle introduced him to the joys of local theatre. Father had a tyre business in Jaipur, the Hindi film industry was too distant to even be a dream.

Yet, the Great Leveller saw them both succumb to the complications of cancer in two famous Mumbai hospitals last week; the janaaza and the antim sanskar conducted with face masks and gloves during a painfully restrictive lockdown in the country; both so famous that prime time television and the Internet went viral with the mourning.

Irrfan didn’t even want to flaunt the “Khan” in his name. Rishi was every inch a Kapoor.

Irrfan went to the National School of Drama to learn acting and met his wife, writer Sutapa Sikdar, there. Irrfan began with a one-day job in Mira Nair’s Salaam Bombay (1988), where he asked for Rs 5,000 and was paid Rs 2,000. He had it tough, dabbling in television serials without creating a ripple, before Maqbool (2003) brought him to the fore as an actor with an indescribable presence of his own. He had begun to be recognised but saleability — which came 14 years after Salaam Bombay with his first big solo hit, Paan Singh Tomar — the thought of casting him opposite a beautiful heroine (with Deepika Padukone Piku 2015) or finding him power a film with his presence (The Lunchbox 2013, Talvar 2015, Hindi Medium 2017) took years. Hindi Medium came to him only in 2017 and a neuroendocrine tumour came visiting by February 2018 itself?

Irrfan moved into a beautiful house in 2017 with artistic interiors by Shabnam Gupta (who had done up a spate of exclusive homes such as Aditya Chopra’s). And he enjoyed his well-earned success and comfort for barely one year before hospital beds beckoned? But you couldn’t see any of it on his face — he was always so ready with a chuckle.

I once had a long conversation with him over his marriage. And he happily talked about the contradictions in his life.

Although he was devoted to Sutapa, “I never wanted to get married. I wanted to focus all my attention on my career. Yet my body and soul were longing to belong to somebody. At the same time I thought such an attachment would distract me from my life’s desire to become somebody.”

When he met Sutapa, “We’d talk a lot, argue, debate, criticise. Basically, we were friends who shared a lot. So, after a point, we just came together physically and began to live together. I couldn’t find anybody else with whom I could share more than I did with her. So we just lived together for a long time.” He would casually drop little bombs and watch the reaction with a smile.

They were happy the way they were. “Nature has not told human beings to get married,” he said, “but because of society you need a certificate.” And so they wed, in February 1995, notching up a wonderful silver this February, two months before he slipped away.

Quite in contrast, Rishi Kapoor didn’t know the meaning of struggle. Introduced as an actor by his father in Mera Naam Joker (1970) and launched as a romantic hero in Bobby (1973), Rishi was the first person I ever interviewed. It was at RK Studio during the shooting of Bobby — so he and I more or less started our careers together, although I continued to study and graduated while he was pleased to have cleared school. But, like marriage, a degree too is sometimes just a certificate as Rishi was a well-spoken man, eloquent in both English and Hindi.

When he was wooing Neetu, his constant co-star, he would never come out and admit it officially. One Sunday evening, I was chatting with Neetu and her mom at their Pali Hill apartment when he turned up. I had to hide behind a door because Neetu knew he wouldn’t want to be “caught in the act” by a journo.

On the sets, he liked playing cards, which was his one big connection with Neetu’s mom, Raji Singh.

He did things in style. At the outdoor shooting of Phool Khile Hain Gulshan Gulshan in Kolhapur, he was very propah in inviting me to his room for a cuppa and a chat. Another time when we were scheduled to do an interview in Mumbai, he said, “Let me take you out to lunch.” He was chivalrous, he complimented me on my clothes, he opened doors, pulled chairs and most of all, gave me a great interview.

He pulled no punches when he talked but didn’t like it when Neetu gave me an interview against Rajesh Khanna, in which she called him a few names. “That’s not done, unprofessional,” he had scolded her and me.

Twitterati was introduced to the outspoken Rishi Kapoor but that’s how he always was. Even though one must admit that tell-it-like-it-is was a one-way street with him. He could tick off anybody but couldn’t quite take it if anybody told him a few hometruths.

Another trait: turning off the lights mid-conversation was his way of letting guests at his lovely bungalow in Pali Hill know that it was time for them to leave. That bungalow with so many memories, now demolished to make way for independent new residential spaces for Ranbir and parents, is a home that Rishi sadly didn’t live long enough to see.

One of his favourite co-stars, who was also one of the last to meet him, was Juhi Chawla. She went across to the hospital where he had gone for a quick procedure. This was just before Rishi had enthusiastically banged a thali at 5pm to respond to the Prime Minister’s call to thank the essential services providers on Sunday, March 22. A clip that was played ad nauseam everywhere. Spirited, articulate and a celebrity till the very end.

RIP Irrfan, cheerful always.

RIP Chintu, quite literally, “my first hero”.

Bharathi S. Pradhan is a senior journalist and author