Eastwood’s latest curmudgeon is Earl Stone, one of those hard movie men in need of a deep-tissue softening. It’s 2005, and Earl has a small, thriving business growing and hybridising the day lilies that are his passion. He has a family that he has long neglected without much apparent regret. Soon after the movie opens, he skips the wedding of his daughter (Alison Eastwood, the filmmaker’s admirably game daughter), to attend a day-lily conference where he’s greeted like a rock star. Missing the wedding is meant to be bad even if the image of an exuberant Earl rolling up to the conference wearing a rakish grin and a seersucker suit suggests otherwise.

A few beats later, it’s 2017, and Earl’s life has gone catastrophically south. He loses his business and home, and is forced to dismiss his small work crew. With his belongings precariously piled in his pickup, he enters a new chapter. He is rejected by his closest relatives, all women — wife, daughter, granddaughter — further isolating him. His salvation comes from a stranger, who offers help by way of some mysterious introductions. Shortly after, Earl meets the heavily armed and tattooed stateside emissaries of a Mexican drug cartel and begins running cocaine, which Eastwood makes look kind of fun.

The Mule was inspired by a startling 2014 article in The New York Times Magazine by Sam Dolnick, There’s a True Story Behind ‘The Mule’: The Sinaloa Cartel’s 90-Year-Old Drug Mule. The mule was Leo Sharp, a World War II veteran and great-grandfather who came across in news accounts as an unsolved puzzle. Working from Nick Schenk’s script, Eastwood fills in the portrait of his mule with creative licence, characteristic dry humour and a looseness that seems almost completely untethered from the world of murderous cartels. There’s also some political editorialising and a flirtation with Eastwoodian autocritique.

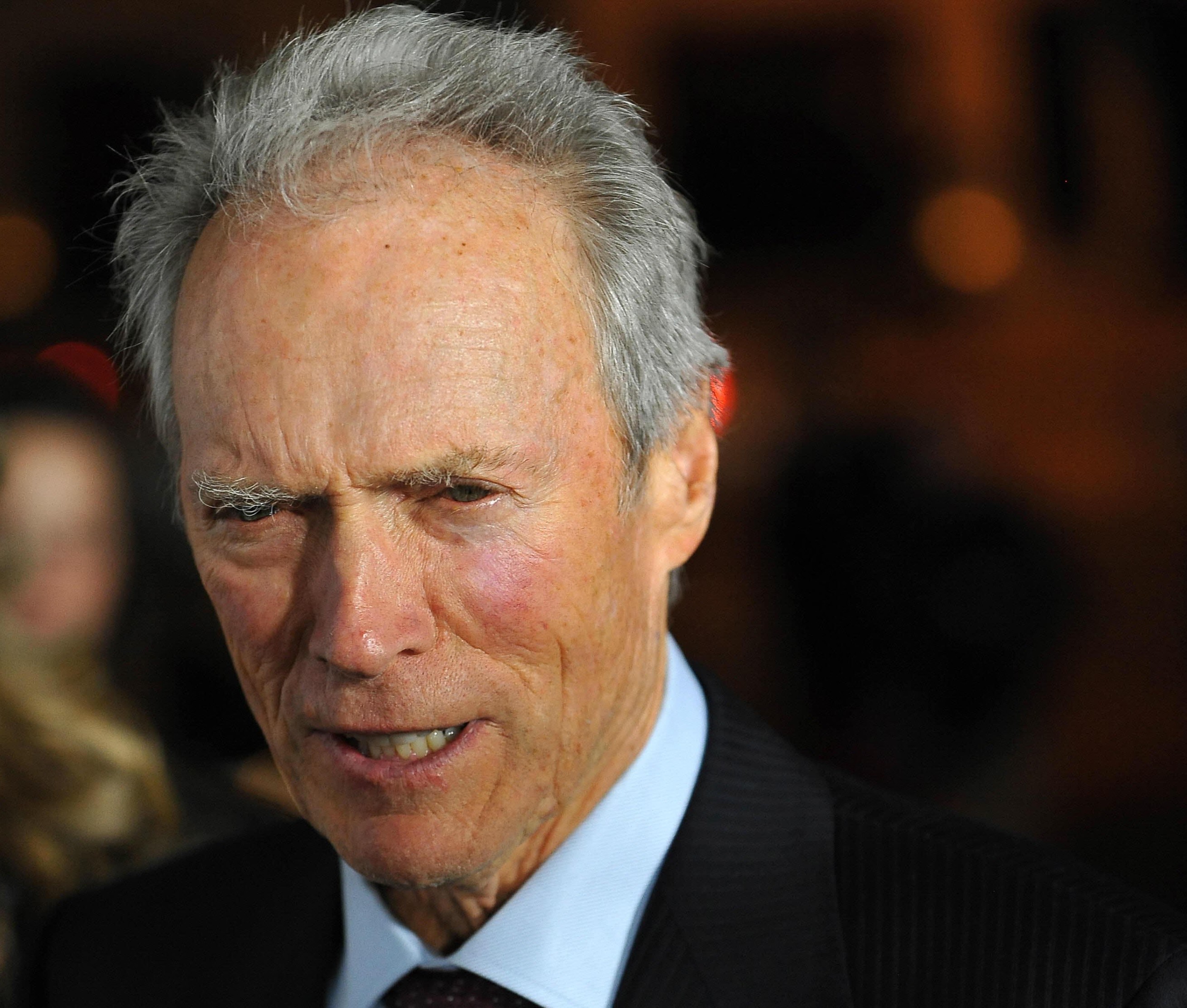

From the start, Earl is a breezy charmer who enjoys his new job (and driving), and is tickled by the fat envelopes of cash he receives from the cartel. Eastwood’s affable performance and unfussy, minimalist approach make the story motor along nice and easy, especially since no one seems concerned with the misery Earl blithely helps spread. Some of the most satisfying scenes are of Earl just driving, largely because Eastwood is a totemic presence; he’s also 88 now. This is the first movie he’s starred in since Trouble With the Curve (2012), and he seems papery, fragile, which gives the movie a wistful poignancy that has nothing to do with the story and everything to do with Eastwood.

Earl’s apparent immortality and lack of curiosity about his gig feel bracingly promising, suggesting that the movie is shaping into a scathing, relevant portrait of American greed. That’s particularly true as the miles and kilos rack up, and Earl’s somewhat Forrest Gump-like innocence feels increasingly disingenuous. For a while it’s tough to get a bead on Earl, which makes him seem intriguing even when he’s just cruising and singing along to Dean Martin’s rendition of Ain’t That a Kick in the Head? That song’s casual leering — How lucky can one guy be? — lends a sleazy undertow to the movie that feels right, suggesting that it is heading into deeply ironic terrain.

It never gets there. Instead, the story shifts and lumbers toward redemption that Earl doesn’t earn and that sentimentalises a movie that is never especially good and often teasingly offensive but also fitfully entertaining and willfully perverse. It offers up a seemingly irredeemable, solitary man — and here I mean Earl — who learns to exist with, and care about, others, whether cartel members or his forgiving ex (Dianne Wiest). At times, as when Earl uses abusive language to describe characters’ racial, ethnic or sexual identities — only to smilingly signal he’s okay with them — Eastwood seems to be simultaneously tweaking and accepting what he presumably regards as social pieties.

These moments may make you laugh or wince or both. But because the movie never builds to something greater than its parts, Eastwood ends up blowing raspberries and floundering for meaning in a void.

A crisp Bradley Cooper throws lines around with Michael Pena and Laurence Fishburne; they’re fine company. Earl visits the cartel boss (Andy Garcia) who — from the looks of his pad and bikinied babes — is a connoisseur of exploitation flicks about drug lords. These scenes are silly and impossible to take seriously even when blood flows, though they do afford you the opportunity to watch Eastwood’s not-yet-repentant, gleeful dog getting down and dirty.

Clint Eastwood has been doing the crusty curmudgeon thing for a while. Sometimes it’s a bad fit, Exhibit A being his chat with an empty chair at the 2012 Republican National Convention. Sometimes, though, he turns growls into meaning, as in Gran Torino, about a racist former autoworker who finds redemption the good old-fashioned American-Eastwood way: in violence. That’s a trajectory he’s embraced with varied results, most recently in The 15:17 to Paris, a fascinatingly odd experiment in realism that is preoccupied with what it means to be a man.