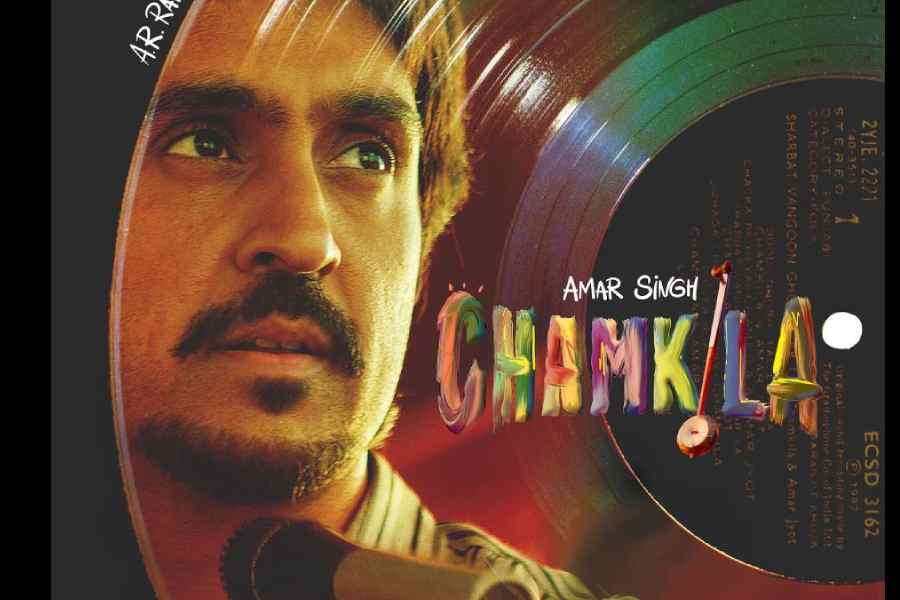

In terms of recasting of the biopic genre, Amar Singh Chamkila is a towering achievement. Director Imtiaz Ali, aided by brother Sajid Ali as co-writer, the experienced scissors of editor Aarti Bajaj, Sylvester Fonseca’s unique ability to find soul and sublimity in every corner of every frame of the camera and A.R. Rahman in apogee form, crafts a story on the life and times of an ordinary man who lived an extraordinary life and is fittingly told in an unconventional manner.

Using music — a lot of what is Chamkila’s own and some of it Rahman’s — Imtiaz weaves a stirring portrait of the meteoric rise and grisly end of a man whose primary aim was to entertain the world through what he wrote and sang. The filmmaker, whose tryst with telling a story through its musicality reached its peak with Rockstar more than a decade ago, invents an all-new narrative structure in Amar Singh Chamkila.

To describe this film, streaming on Netflix, as merely a biopic would be limiting its scope and ambition. Imtiaz fashions a compelling look at Chamkila’s intentions and actions, presenting the man not only through the various stages of his short life — Chamkila was snuffed out at 27, making him a part of the infamous ‘27 Club’ of globally-renowned musicians who died at that age — but also the diverse moods and moments he goes through in his dizzying rise to unbridled success and unchallenged popularity. There is a loss of innocence in his journey and yet the somewhat incorruptible nature of Chamkila’s personality (even when he was responsible for writing some extremely lewd lyrics) shines through and makes a place in the heart of the viewer.

That is, in large measure, due to the manner in which Diljit Dosanjh embraces the man. “Diljit’s personality was key to making this film. All that he has done for this film was out of his love for Chamkila,” Imtiaz had told t2 in the run-up to the release of the film. His words couldn’t have been more on point.

In demeanour, voice and attitude, Diljit becomes such a part of Chamkila, his world and his vibe that it is almost impossible to think that he isn’t actually the man he is playing. Through him, you celebrate Chamkila even when he sings uncomfortable lines like: “Teri maa aur mera baap kaand kar gaye” or delivers life truths such as: “Thirakta reh, matakta reh, jo hona ho woh ho”.

It was this ribald rebellion that defined Chamkila in life and in death. Amar Singh Chamkila opens with the daylight murder of the musician, along with that of his wife and co-performer Amarjot (Parineeti Chopra), as they alight out of their grey Ambassador to sing at a show. The date is March 8, 1988, the place Mehsampur. Killed instantaneously and with their lifeless bodies lying in the middle of a dusty field, the narrative jumps to the opening credits in which a balladeer of sorts — singer Mohit Chauhan’s vocals power the song, with the man also making an appearance on screen — describing Chamkila as the shining star who lived and died for art. But it doesn’t shy away from using words like “tharkila Chamkila” and “ganda banda, social darinda”. This is no whitewashed biopic but one in which its subject is presented warts and all.

And yet there is no denying that Chamkila, who graduated from making socks in a factory to weaving magic through his music, his omnipresent tumbi almost doing the work of a wand, was living the life that every young man in Punjab at the time aspired to. This grassroots singer, by dint of being the highest-selling artiste in the state at the time, was often referred to as the “Elvis of Punjab”. Chamkila was well aware of the hold he had on his audience. At one point, he tells someone: “I am Amitabh Bachchan for the public.” During a performance, when the roof of a house comes crushing down under the weight of Chamkila’s cheering spectators, he promptly earns the adage of ‘Kotha dhau kalakaar’ aka ‘roof breaker’.

Chamkila’s popularity brings in big bucks and global acclaim (he moves from makeshift stages in the Pind to stadiums in Bahrain and Canada) but also death threats from militants, religious leaders and self-styled cultural gatekeepers.

The man, however, powers on, the lasciviousness of his lyrics almost becoming an anthem of liberation for the women he is said to objectify. Through the pulsating beats of Naram kaalja, Imtiaz and Rahman, with Irshad Kamil’s pen doing its work, make women of present-day rural Punjab come out in support of Chamkila, through music. When translated, one powerful line reads: “You plunder my body thinking it is macho but it is only a form of pleasure for me.”

The film, using the murders as a pivot, moves seamlessly between the past and present, with split screen, real-life footage of Chamkila and Amarjot and with some parts even playing out like a graphic novel, shedding light on how Chamkila’s music provided succour to a militancy-dominated state in the ’80s and emphasises on the fact that Chamkila’s talent lay beyond his penchant for lewd lyrics. At one point, Chamkila, faced with threats, shifts to creating devotional music, the album for which sells higher than any of his previous work and at three times its price in the black market.

Amar Singh Chamkila, however, may seem overlong and repetitive in parts and Parineeti’s performance, to be honest, pales in comparison to Diljit’s scenery-chewing act. Especially, when an undaunted Chamkila, his eyes blazing, sums up the spirit and soul of the man with: “Jeete ji marne se achha hain ki marr kar zinda rahein.”

I liked/ didn’t like Amar Singh Chamkila because...

Tell t2@abp.in