The name Gulzar is a world in itself. It stands for purity of thought and excellence in writing. It is a descriptor that needs nothing else to define it. Gulzar means ‘garden’ and symbolises beauty, warmth and abundance. Much like the legend whose creative talent and skill with the written word has defined and refined the standard for Urdu writing over the past few decades.

Gulzar, one of the finest the country has ever had, may be known as a lyricist, author, screenwriter and filmmaker, but his influence and impact on the written word — in cinema and beyond — is far-reaching. He has won an Oscar for Best Original Song for Slumdog Millionaire and was honoured with the Jnanpith Award, the oldest and highest literary award in India, in 2024.

Gulzar saab’s latest book Caged, a deeply touching and intimate portrait of his life told through the people who have impacted and influenced it, is now on the stands. Written in poetry form, the book, penned in Hindustani and translated in English, is a compelling peek into the life and times, thoughts and memories of Gulzar saab. On a recent January afternoon, I found myself sitting face-to-face with him at his home in Mumbai. Over the next hour or so, Gulzar saab tapped into the rich treasure trove of his memories to take us through the magical journey called Caged, and hence, through his life. A t2oS exclusive.

“One question that I have been constantly asked over the years is: ‘When are you writing your autobiography?’” Gulzar saab, dressed in his trademark crisp white kurta pyjama, tells me as we commence our conversation. “I never wanted to write an autobiography which conveys already-known information,” he smiles. “For me, an autobiography means the life experiences that one has had. One doesn’t experience life on one’s own... it is not an individualistic experience. You experience life through what you have lived and through the people you have met. The connections I have built in my life and the impact that they have had on me. That is what forms the core of Caged,” he says.

This is not the first time that Gulzar saab has narrated key moments and memories of his life through his interactions with those who have walked through it, stayed with him and contributed significantly to his journey of life. His book Actually... I Met Them, released in 2021, talks about his deep connection and collaboration with many notable names. Memories form an integral part of that book — “Memories never dry up. They keep floating somewhere between the conscious and the subconscious mind. It is a great feeling to swim there sometime,” Gulzar saab had said at that time. He revisits many of those memories, with some of the names being common to both Actually... I Met Them and Caged. But while the former is in prose, he has chosen the medium of poetry for Caged.

MOMENTS LIVED & FELT

Caged starts with him talking about the influence of Rabindranath Tagore in his life and work. The Bengal connection has always been strong in his life. There is his relationship with musical geniuses R.D. Burman, Salil Chowdhury and Hemanta Mukherjee, which travelled beyond mere professional collaborations; he was mentored by filmmaker Bimal Roy (‘Everything I know about filmmaking is from him,’ Gulzar saab writes in Caged) to almost making Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne in Hindi under the aegis of Satyajit Ray. From his translated works originally in the Bengali language to even writing firsthand in Bangla — in this interview, he spoke fondly about his befittingly named book Pantabhaate. During this interaction, he broke spontaneously and seamlessly into chaste Bangla, a language and people he holds close to his heart.

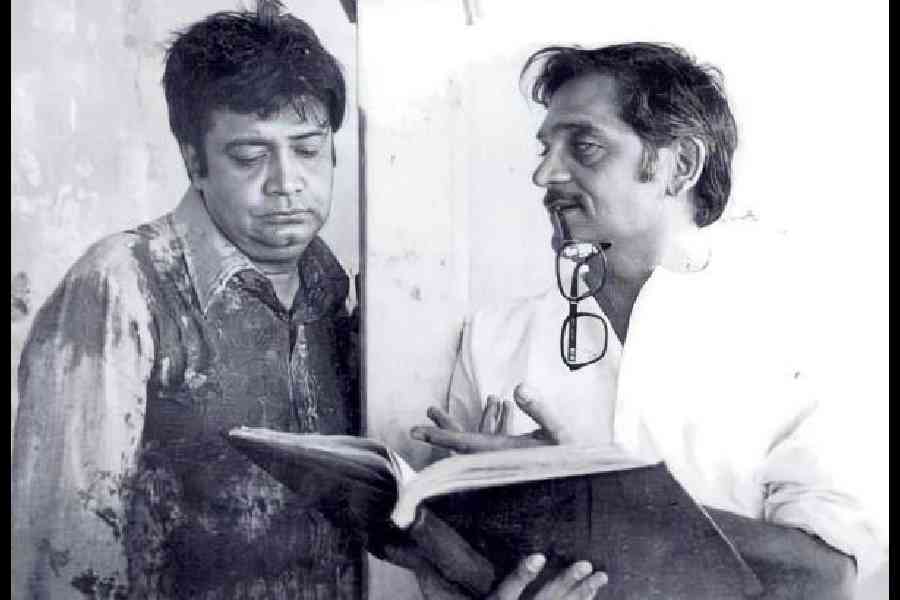

With actor Deven Verma on the sets of Angoor

“I have worked with some gurus, some great masters from Bengal,” he says. “To be mentored by Bimalda (Roy) was a blessing and a privilege. To get a chance to hone my craft with Sachin Dev Burman (S.D. Burman) and to be able to work with Salil Chowdhury, a great legend (in Caged, he headlines the chapter on Salil Chowdhury as ‘Salil Chowdhury The Genius’)... sometimes I can’t believe that all of this has happened in one lifetime for me,” he says, his voice trailing off, perhaps recalling the days of yore.

Gulzar saab’s Bengal connect, he believes, remains incomplete without the mention of Mahasweta Devi. “I wrote the screenplay for the film (Sunghursh, 1968) based on Mahasweta Devi’s Layli Asmaner Ayna. The conversation opens up a flood of memories within him. He recalls the days he spent with Pandit Ravi Shankar — “I roamed the country while he composed music for Meera (Gulzar’s 1979 film for which Pandit Ravi Shankar was the music director). I have travelled with Hemantada (Hemanta Mukherjee) to the mofussil towns of West Bengal for his programmes. His performance would start at midnight and he would sing till dawn,” he smiles. “I started working for Ray saab (Satyajit Ray) for Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne when he wanted to do it in Hindustani. When I read the preface to Caged, I have to pinch myself that I have actually met all these people.”

I ask him what inspired the name Caged. The answer, as is expected from Gulzar saab, is profoundly beautiful and beautifully profound. “It is because the root of this book comes from the feeling of me holding a butterfly. The butterfly flew away but she left some colours on my hand, my fingers. I have tried to preserve that... those are my memories. People generally pin butterflies, they make albums out of them. But I didn’t do that. I have caged those memories, those features and those personalities in my poems, so that I don’t let those moments fly off. I have caged them in my poems. My journey from Pantabhaate to Caged is my autobiography,” says Gulzar saab.

He dedicates the majority of Caged to his memories and meetings, but also pays tribute to those he hasn’t met. For instance, he cites Dutch Post-Impressionist painter Vincent Van Gogh as an influence as well as Neil Armstrong, the first man to land on the moon, as an inspiration. “I was always very keen on learning about space and Neil Armstrong had a deep influence on me. But when he passed away, we hardly wrote anything about him (‘Jab hamesha ke liye zameen chhod gaya, toh hum mein se kisi ne yaad naa kiya usey’ he writes about Armstrong in Caged). He was not an American; he was a citizen of the world. He is related to you and me as much as he is related to anybody else. The world didn’t acknowledge that,” says he, ruefully. “Hence, I paid my compliment to him. It is my way of saying that he lifted me — and all of mankind — when he set foot on the moon.”

Caged touches upon and pays tribute to the friendships that Gulzar saab has carefully nurtured over many decades. One of them is with the legendary flautist Hariprasad Chaurasia.

‘Saaton baar bole bansi/ ek hi baar bole na/ tann ki laagi saari bole/ mann ki laagi khole na’ — Gulzar saab on the flute and Pandit Hariprasad Chaurasia in Caged.

These lines on the dual nature of the flute, one which brings alive the seven sur but reveals little about itself could have perhaps only come from the head and heart of Gulzar saab. “I wanted to dedicate these lines to Pandit Hariprasad Chaurasia... aapne saaton sur zinda kar diye mere liye aur main aap ki mann ki baat jaanta hoon.”

We were sitting in Boskyana, Gulzar saab’s abode, in Pali Hill, Bandra. Named after his daughter, filmmaker Meghna Gulzar (her nickname is Bosky), the bungalow has a rich legacy housed within its walls — photographs, trophies, memorabilia and even people that Gulzar saab holds close to his heart. Like his assistant, a shy, smiling lady, who has been working with him for 25 years. “She knows more about my writing than I do,” he laughs. His driver, he says, has been with him for 50 years now.

It is this power of human connection that has always defined Gulzar saab. A chapter in Caged talks about Sukrita, the daughter of the renowned Urdu fiction writer Joginder Paul. It is a bond that he holds close to his heart. “When I am in Delhi, my dinners are always with Sukrita. If we have to go somewhere, she drives. And she talks so much that she invariably gets us lost on the roads,” he laughs.

A chapter is dedicated to ‘Anjal’, short for Geetanjali, a 14-year-old admirer of Gulzar saab’s writings, who lost a hard-fought battle to cancer. He takes a pause before he talks about the young girl. “She was perhaps on her last one or two nights of cancer. It was only after her death that I met her mother, who told me that her daughter was very fond of my poetry. In fact, the young girl had written some poems herself, which the mother published later.”

LIFE & BEYOND

Death is an omnipresent entity in Caged. But Gulzar saab refuses to look at it morbidly, choosing to define death as a transition. His collaborations with other artistes have transcended the professional space and become personal. And while many of them may have passed on, their memories indelibly remain with him. In Caged, he writes about life being transient, about how the spirit wears no robe. He writes about cremating and burying his close friends and colleagues, and yet holding on to a part of them.

Particularly poignant are the lines penned for Rahul Dev Burman, with whom Gulzar saab not only did some of his finest work but also formed a friendship like few others. In the chapter titled ‘Pancham’, he writes:‘Tum yuhi do kadam chal kar dhund par paav rakh kar chal bhi diye. Main akela hoon dhund mein, Pancham’.

I asked him about how he views death and whether its meaning for him has changed over the years. “I have written about the poet Namdeo’s cremation and about Pali, my Boxer, that death snatched away from me (in Caged, he writes about death, with special reference to his pet Pali: ‘Yeh sab khaati hain. Koi zaat hain iss maut ki na dharam hain koyi’).”

“A few deaths happened in front of me. They did touch me. The good thing is that it is only in our culture that death is not morbid. We talk about death beautifully, even in our shastras. It is so lyrical only in our culture. For us, death is at times a dulhan and at other times, a dulha. I look at death as another journey, another life. But I did feel the pain when (filmmaker) Shyam Benegal passed away the other day. It affected me,” he says.

But what has consistently provided succour to his spiritual soul is the belief that those who have passed continue to be with him. “I left Amjad (Khan, actor) at the burial ground, but he came back with me (‘Main neem andheri kabr mein sula raha tha jab usey/ toh neem-wa-nigaah se woh dekhta raha mujhe’, is what Gulzar saab writes about the demise of the iconic actor in Caged).

A recent death that he says has affected him deeply is that of tabla maestro Zakir Hussain. “I used to be very close to him. I worked with his father Ustad Alla Rakha Khan saab, who would cook mutton for us even in the middle of giving tabla lessons! Zakir was very young then, but he would come and sit with me.” He also goes on to talk about the late Pandit Birju Maharaj, the legendary exponent of Kathak. “I have lived with these people. They have been my gurus. With Alla Rakha saab, I was not only learning how to play the tabla, I was learning life from him. The rhythm that I learnt from him was not only of tabla, there is a rhythm of life that I picked up in the process.” Who does he miss the most, I ask him. He refuses to answer it, simply saying: “You can’t make a book if you love only one poem. Experiences stay with you forever. That is how it is.”

LOOKING BACK

Staying true to one’s roots has always reflected in Gulzar saab’s writing and, in many ways, it is also seen in Caged. He writes about Munshi Premchand: ‘Sheher aakar log unhein bhool jaate hain. Isi liye unse milne ke liye apni jado par waapas jaana padta hain’. In that context, Gulzar saab spoke about how and why his roots define who he is. His brothers have moved to the West, with the second-generation of the family now fully embedded in that culture. “When my brothers come to India, they crave the kind of dal that is made here. That is our culture, and that is why I love living in my country. I am proud to be an Indian.”

Gulzar saab has stayed true to his roots by writing in Urdu. “I have been schooled in Urdu. I belong to that period where all males in Delhi and Punjab, in the British era, used to study Urdu. My grandparents and the generation before that were schooled in Urdu.” A young Gulzar — a teenager of 13 — witnessed the Partition, which he describes as “one of the most horrible things in our political and cultural history”. He has chronicled the trauma of that period in Footprints on Zero Line: Writings on the Partition. “Witnessing the Partition firsthand takes me back to it time and again in my writings,” he says.

Every line penned by Gulzar saab in Caged has been translated into English by Sathya Saran, a short story writer and poet herself. “I encourage being bilingual because we have so many different languages and dialects in India. How would I have been able to read K. Satchidanandan if his writings had not been translated from Malayalam? My book has been translated so that it reaches out to a wider audience. If one can read English, do read it. Let us travel a few steps together,” he smiles.

‘Memories have names’ is the logline of Caged and along with it and And Actually... I Met Them, Gulzar saab has written about the ‘names of his memories’ in Dhoop Aane Do, a Marathi text which has also been translated into English. He relates a hilarious tale about a cook in his household named Ramu who finds mention in Dhoop Aane Do. “Ramu ran away about 12-14 times during the time he worked here. But every time, he would come back, even if it was a year later!” he chuckles.

The fact that Gulzar saab has a vast body of work as poet, filmmaker, writer and more doesn’t need to be reiterated. What caught my attention in Caged, however, was him saying that Mirza Ghalib, the 1988 TV series on Doordarshan that he wrote and directed on the legendary poet, was his best work. He also thanked actor Naseeruddin Shah, who played Ghalib, for bringing alive “one of my finest creations”. Why did he think that was his most exemplary work, I asked Gulzar saab. “I hold it in high esteem because before that, in any other portrayal, Ghalib wasn’t shown as a real person. Mirza Ghalib did that, perhaps for the first time. Even Jagjit (Singh, who composed for and sang in the series) had said it was his favourite.”

‘I WEDDED BANGLA’

Our conversation invariably veers back to Gulzar’s love for Bangla (‘I wedded Bangla’ / ‘Byaah gaye Bangla se’, Gulzar saab writes in the very first chapter of Caged, dedicated to Rabindranath Tagore). What is it about Bangla and the Bengali connection that has had such a huge impact on him, I ask. “Culturally and from the literature point of view, I am very close to Bengal. I have written about Uttam Kumar and Suchitra Sen in The Telegraph. I have directed both of them (Uttam in Kitaab and Suchitra in Aandhi) in my films. My first film as director (Mere Apne, 1971) was based on Tapanda’s (Tapan Sinha) Apanjan. Apanjan beautifully depicted the raw, real lives of the youth of Bengal at that time. I asked him for the rights. I rewrote the film because I needed to recontextualise it, but retained the same cultural feel. I think our culture of 5,000 years is so rich that you can’t erase it, you can’t do anything with it. It runs in our blood,” says Gulzar saab, his voice firm and fervent.

FOOD FOR THOUGHT

Out of Gulzar’s many connections with Bengal and Bangla, one is definitely of food. “There was no one who could cook like Pancham. He would make the best pork,” he smiles. In his book, he writes about how Asha Bhosle, who he and Pancham collaborated with on many occasions and who, of course, was married to the latter, would cook the most delicious mutton. ‘I address her as Boudi because of my relationship with Pancham,’ he writes in Caged. “Salilda (Chowdhury) was also a very good cook,” he tells me.

Caged has a chapter on ‘Anjana Bhabi’, producer S.H. Rawail’s wife. A Bengali, Anjana took to Punjabi culture effortlessly. ‘No Punjabi would ever say that she was from Bengal. And no Bengali who heard her speak would say she was a Punjaban,’ Gulzar saab writes about Anjana. “When she used to sit on the dholak and sing Punjabi songs, the way she used to talk, nobody could even suspect that she was a Bengali,” he reminisces during our conversation. “These are the kind of people who touched my life.”

Food forms deep bonds and Gulzar saab couldn’t agree more. He smiles as he talks about tabla sessions with Ustad Alla Rakha Khan even as he cooked up a storm. “Ustad saab would multitask and do both at the same time. That was an experience for me,” he smiles.

As I get up to bid goodbye after a stimulating conversation of close to an hour, I ask Gulzar saab about the story behind the illustrations in his book. Turns out he has done them himself. “I was just sitting and doodling with pencils made of charcoal. My editor Premanka (Goswami from Penguin Random House India) asked me if he could use them. He selected a few and here we are,” he says.

As I slowly make my way out after a hug and a signed copy of Caged from him, Gulzar saab speaks about an impending meeting with close collaborator Vishal Bhardwaj. “Till two years ago, we would play tennis regularly,” says he, now 90. The mind, however, still young and ticking, continues to serve one ace after another.