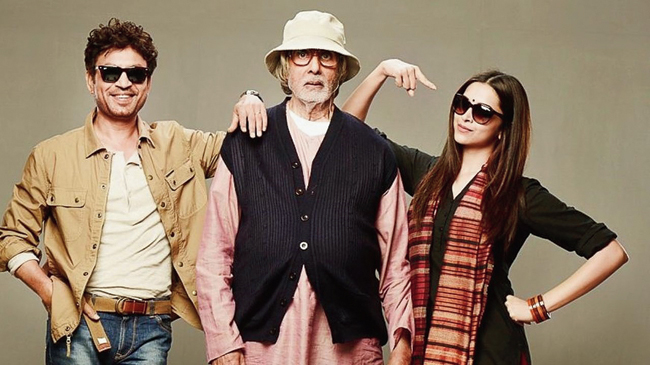

A septuagenarian obsessed with his bowel movements. That is the core of Piku. But the Shoojit Sircar film — that touchingly portrays a father-daughter relationship, fraught with tension, but also tempered with love, empathy and understanding, and peopled with quirky characters — is a winner that scores high on relatability. Piku, that turns five today, brings on the belly laughs as well as the lump in the throat, and is a film we rewatch at every available opportunity. The Telegraph spotlights what makes Piku, with Deepika Padukone portraying the title role and Amitabh Bachchan and Irrfan giving the film both its heart and humour, one of the best films of the decade gone by.

The father-daughter dynamic

Fathers and daughters is a theme as old as cinema itself. In Piku, the nature of the quirky yet relatable relationship between the 30-something Piku (Deepika Padukone) and her father Bhaskor Banerjee (Amitabh Bachchan), a 70-year-old hypochondriac, is established within the first few scenes. Residing in Chittaranjan Park, the Bengali hub of the national capital, the conversations between the two, for the major part of the film, centre on a much-loved Bengali obsession, bordering on mania.... Bhaskor’s bowel movements, or the lack of it.

A victim of chronic constipation, Bhaskor’s favourite pastime is to discuss — in great detail, right down to colour and texture — his daily (sometimes, not so daily) bowel habits, mostly with Piku, of course. That gives rise to a number of hilarious scenes — from Bhaskor describing his stool (“semi-liquid motion first, followed by gas and constipation for two days”) in a publicly read-out memo in Piku’s office, to “hard mucus and then mango pulp” as he describes it to Piku in the middle of her dinner date, that invariably, of course, went wrong.

This is a dynamic that makes us laugh out loud and yet is one we readily identify with. Bhaskor, hell-bent on ensuring that Piku remains his caregiver till his last days, always has one foot forward to ruin her marriage prospects, often publicly discussing the fact that she is “sexually independent and not a virgin”. That leads to serious arguments between the two, but one look at her father and all of Piku’s anger melts away, especially in that endearing moment when she watches him dance with abandon and glee to Jibone ki paabo na.

We love the beautifully etched-out moments between the two, which form the core of Piku. Whether it is Bhaskor and Piku singing Ei poth jodi na shesh hoy and egging each other to say “Tumi bolo”; Piku not knowing whether to laugh or cry when a gutted Bhaskor takes a peek at his test results and says dejectedly, “Sab kuch normal hai?”; or that moment, in the middle of a frenzied fight, when Bhaskor tells Piku, “I am your child... you take care of me”.

The nature of Piku and Bhaskor’s see-saw relationship is well and truly summed up in the scene on the Calcutta riverside where Piku and Rana (Irrfan) discuss life and relationships, and invariably Bhaskor, and she tells him matter-of-factly, “Parents ek age ke baad akele zinda nahin reh paate, unko zinda rakhna padta hai. Aur yeh bachchon ki zimmedaari hai”.

Still from the film

Bhaskor the cantankerous

Bhaskor Banerjee — armed with a belly, a caustic tongue and oscillating between childlike and childish — is the life of the film. Despite the dodgy accent, few could have brought so much fun and fabulousness to the sometimes caring but often crotchety old man as Amitabh Bachchan does. So taken up is Bhaskor with his motions that all his emotions hinge on it. He could be a pain at times, especially in his bullheadedness and selfishness, but underneath that gruff exterior is the heart of a man who deeply cares for his daughter. Most of Piku’s laughs are courtesy Bhaskor and his bowels, especially his predilection to try out every kind of “home remedy” that Rana comes up with (ingesting pudina leaves to trying his luck in an ‘Indian-styled’ toilet pot to masticating his food like a cow). His glee while riding a cycle through the lanes and bylanes of Calcutta, followed by, “Odbhut... like never before... the best motion”, is a delight. All of us shed a tear in the dark theatre when Bhaskor passes on, but when we walk out, we mostly remember him for the laughs he brought on.

“Bhaskor is one of my most personal characters. When I wrote his death scene in Piku, I actually howled for days. It just felt so personal,” Juhi Chaturvedi, the film’s writer, had told t2.

Still from the film

Being Piku

Parineeti Chopra was reportedly offered the role first, but truth be told, we can’t think of anyone but Deepika as Piku. As the perpetually on the edge young woman looking after a mostly impossible father and managing the responsibilities of home and career, Piku’s frustrations are palpable. Deepika brings both heft and heart to the part, looking like a million bucks in those simple salwar suits, and also articulating the needs and wants of a woman. Piku wants to travel the world, meet and marry a man and have a family and life of her own, but she gives it up momentarily to take care of her father. There is so much to relate to in Piku, and Deepika — mostly speaking with those eyes and often through her tears — makes the character one of flesh and blood, from the mood swings to the sudden outbursts, from the childlike woman (like that shot of Piku staring out of the window of her Calcutta home at a group of young girls going for their dance class) to the dutiful daughter. “This was a family where a daughter has to become a mother,” Juhi had told The Telegraph.

Rana: the man with the best lines

Irrfan, oh Irrfan! “Yeh baap beti ke jhik-jhik ke beech mein emotional hoke atak toh nahin gaya main?” Rana asks, at one point in the film. The man is the owner of Himachal Taxi Service who is forced to drive Piku and Bhaskor from Delhi to Calcutta when his driver bails, and finds himself drawn into the dynamics of the Banerjee family. Rana is the voice of reason in Piku and the only one who can shut Bhaskor up, especially when he gets too grouchy with Piku, as it happens in a scene or two on the road trip. If Bhaskor’s humour is straight-off-the-bat, Rana plays it slower, with the results often more effective. From “Kamaal hai... aap har baat pet se kaise jod lete hai” to “Tapak gaye toh Banaras se koi achchi jagah nahin hai” to “Death aur shit kabhi bhi kisi ko aa sakti hai”, Rana has the best lines in the film, with Irrfan, as expected, making them what they turned out to be.

The distinctly Bengali flavour

“Bhaskor Banerjee... Bangali!” That’s how Bhaskor chooses to introduce himself to Rana, who he refers to as “Mr non-Bengali Chaudhury”. Bangali and Bangaliana define every pore of Piku, language to body language. From Bhaskor helping himself to generous dollops of Jharna ghee to the generous sprinkling of Bengali in the film’s dialogues. A lot of Bhaskor’s vocab comprises Bangla, but so does Piku’s (with Deepika choosing to learn up the language instead of letting someone else dub for her). Her accent is spot-on, from the serious “Kichu bolbe?” to the hilarious, “Who uses garam paani to clean their paachha?!'

With the film shifting to Calcutta in Half Two, the city becomes almost a character. From that first shot of Howrah Bridge playing out to the soulful Teri meri baatein to the typical north Calcutta lanes and bylanes, from the palatial family home Champakunj to that distinctly Calcutta motif of Rana and Piku biting into a roll. We wonder if it was double egg, double mutton?

The chemistry

A Bollywood film that depicts romance subtly is rare, but Piku achieves that flawlessly. Piku and Rana start off on a sticky wicket, but he gradually warms to her when he starts understanding the pressures she faces in her equation with her father. She, in turn, is grateful for his presence, even as he acts as a buffer between her and Bhaskor on the road trip. Their quiet chemistry lights up the screen, whether it’s the knowing glances they exchange in the car or the way she cracks up when Rana suggests his constipation remedies to Bhaskor. That moment in the dead of the night on the ghats of Banaras where they exchange a line or two, but mostly speak through their silences, is one of the film’s most telling scenes. The pump repairing scene still makes us smile, and that last shot of Piku and Rana playing badminton, with a promise of a future to come, makes us wonder where they landed up eventually. There was so much more we needed to know about the Piku-Rana love story. If only.

The side players

The trio may make Piku the film it is, but the supporting acts — all quirky, all relatable — gave Piku many of its endearing moments. The scenes between Bhaskor and his sister-in-law Chhobi (a delightful Moushumi Chatterjee) remain memorable, their constant run-ins making us laugh out loud, especially in that one scene where he berates her for marrying thrice instead of taking care of Piku when her mother passed away. “Toh main kya aap se shaadi kar leti?” asks Chhobi, to which Bhaskor says, “Only you can have such idiotic thoughts! Tumko like nahin karne ka mere paas bahut saara reason hai”. The scene ends with Chhobi telling Bhaskor he’s undergoing menopause, which gets the hypochondriac in him thinking... like always. Something that he discusses without fail with Dr Srivastav (Raghubir Yadav), more a friend than a doctor.

Deepika’s colleague and friend with benefits Syed (Jisshu Sengupta) is a quiet presence, with that delightful ‘constipation-related’ scene at the end, while Bodo Mesho (Avijit Dutt) and Moni Kaki (Swaroopa Ghosh, described disdainfully by Chhobi as someone who perpetually wears “a patla nightie ghar pe, that also without a bra”) were delightful. A special word for Bhaskor’s faithful Man Friday Budhan (Balendra Singh), ever ready to do the bidding of his employer, including lugging around Bhaskor’s ‘portable commode’, a wooden chair with a hole in the middle.

Progressive in theme and treatment

Part of Bhaskor’s refusal to get Piku married may stem from his own loneliness and insecurities, but he is also a forward-thinking man in many ways. Like him believing that “marriage without purpose is low IQ” and that a woman doesn’t really need to get married to fit in with societal norms. The film’s portrayal of sex — “It’s a need, maashi”, Piku unhesitatingly tells Chhobi when quizzed about her sex life — to no one batting an eyelid when Syed stays over at Piku’s house often, is refreshing.

The moments

So many moments, big and small, make Piku live on in our hearts today. From Bhaskor obsessing about his ‘fever’ that settles at a normal 98.6 degrees to Budhan, much to Rana’s amazement, imitating ‘susu’ sounds when Bhaskor goes to take a leak on the highway. From the scene where Bhaskor quizzes Rana on his driving aptitude as well as his medical history to the camera panning on the three, sitting by the side of the highway, after arguing over a knife found in the boot of Rana’s car. From Rana drawing a ‘diagram’ to illustrate how sitting on one’s haunches while defecating results in effective bowel movement to Bhaskor arguing with Piku that Elvis Presley died of constipation because his body was found in the bathroom. And then, of course, is the dining table scene towards the end when Bhaskor, in the middle of yet another potty-centric conversation, asks Rana, in all innocence, “Tum itna confidently kaise bol sakta hai ki tum normal hai?” Pure gold.

Motifs

Singhasan: It even made it to the film’s posters. Bhaskor’s carry-with-you-at-all-times makeshift pot — a wooden chair with a hole in the middle — is the film’s enduring motif, referred to by Rana as the old man’s ‘singhasan’. The image of Budhan rushing through the dhaba with the chair on his head so that Bhaskor can carry out his morning ablutions comfortably still cracks us up. “Aapka singhasan toh hai hi... kahin pe bhi bitha denge” are Rana’s words of comfort to a worried Bhaskor (“Not a single piece has come out in two days”) during the road trip.

Cycle: Bhaskor — light pink kurta, grey pants, cap and blue sweater — cycling through the streets of Calcutta — is a distinct image from the film. Cycling, in a way, is a form of catharsis for Bhaskor, giving him a sense of freedom and “the best motion ever”, before he passed on, peacefully in his sleep the next morning.

Badminton: Not only does the final scene — of Piku and Rana playing a spot of badminton, as she gives instructions on the phone for a change in the spelling of Bhaskor’s name on the nameplate in front of the house — indicate a future for the two, badminton also makes its way to another key moment in the film, with Rana and Chhobi mashi playing the game in the courtyard of Champakunj.

The Telegraph: The Telegraph makes its way into the film, not once but twice. Like that celebratory dinner in which Bhaskor’s guests drop in with copies of The Telegraph as a gift and the man goes, “Ah! Nothing like Calcutta news”. In the film’s final moments, the poignant scene in which Piku recalls her recently deceased father with friends and family, has a shot panning to The Telegraph laid out on a table in front of Bhaskor’s photograph.