Hindi, English and European cinema have provided a glittering roster of memorable father figures. From Antonio Ricci in Bicycle Thieves to Atticus Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird. Guido Orefice in Life is Beautiful to Mufasa in The Lion King. Mahavir Phogat in Dangal, Seth Dharamchand in Dil Hai Ke Manta Nahin, Bhashkor Banerjee in Piku.

Looking for screen fathers in Bengali cinema proves somewhat tougher. There is no dearth of iconic mothers – right from Sarbajaya in Pather Panchali to Sarojini Gupta in Unishe April, Bengali mothers onscreen have wowed audiences for decades. But not so much the father. There have been great actors who essayed memorable father characters — Pahari Sanyal, Kamal Majumdar and Chhabi Biswas to name just three.

However, there have been few of the same league as, say, an Atticus Finch. For one, a great star and actor like Uttam Kumar does not have a single role worth the mention as a father. It is then left to the other legend, Soumitra Chatterjee, to essay some of the well-known father figures in Bengali cinema. They may not have all lived up to the demands of fatherhood, but they have all been fathers who have made a difference to their child’s life.

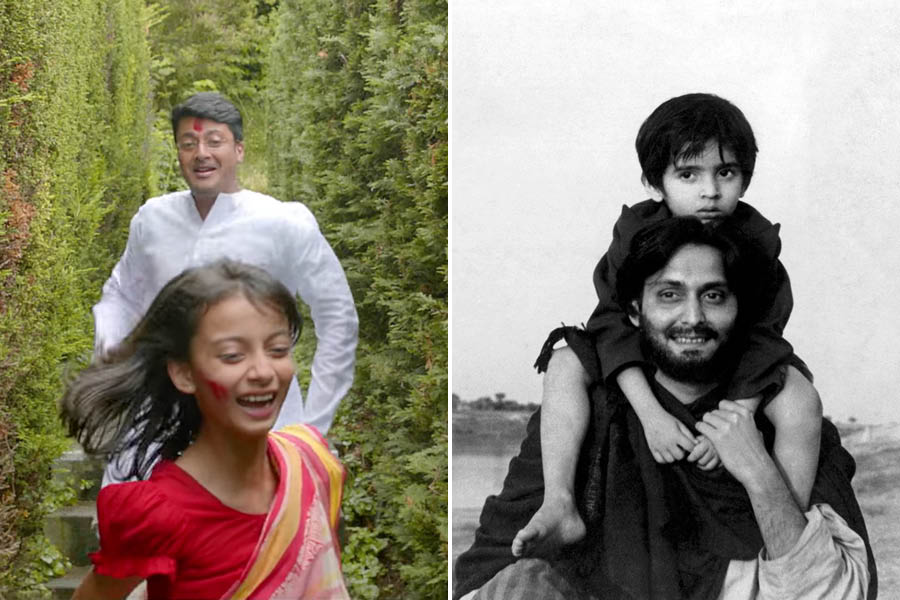

Apur Sansar (1959)

Apur Sansar of course has cinema’s most iconic father and son, culminating in a closing shot that rivals that in Bicycle Thief. Even 60 years after the film was made, the sight of Kajol on Apu’s shoulder is capable of moving the most hardened heart. After the death of his wife, Aparna, at childbirth, Apu has abandoned everything, even his child, choosing the life of a vagabond. Even when his friend Pulu tracks him down and tells Apu about his son Kajol being brought up by his grandfather devoid of all parental care, Apu refuses to go back. He has no feelings for his son. It is because Kajol is alive that Aparna is no more.

Apu eventually finds himself at Kajol’s grandfather’s place, having decided to leave Kajol with his relatives at Nischindipur while he goes on a long sojourn. His father-in-law tells him that Kajol is unwell, recovering from a fever. Apu approaches Kajol’s bed but cannot bring himself to face him. He sits next to a window looking out to the river where we see a boat – the strains of a bhatiyali song are heard on the soundtrack. When at last he musters up the courage to call him, Kajol opens his eyes, looks at Apu and runs away. Apu follows him, calling out, ‘Kajol, I am your father.’ Kajol hurls a stone at him. When his grandfather raises a stick to beat him, Apu intervenes. But his efforts at breaking through to Kajol fail in the face of the latter’s long-standing hurt. Apu decides to leave. As Apu walks away, Kajol follows him at a distance. Apu turns back and we have one of the most moving exchanges in the trilogy, leading to that closing shot: Apu, walking away, with Kajol perched on his shoulders.

Asukh (1999)

Few films have conveyed the workings of a troubled psyche as tellingly as Rituparno Ghosh’s Asukh. Suspecting her fiance of infidelity, Rohini (Debasree Roy), an actress, descends into a dark spiral of doubt and suspicion, at the receiving end of which is her father, played with remarkable poise by Soumitra Chatterjee. As her mother is admitted to a hospital, and she is thrown into close contact with her father, matters get increasingly frayed between the two. Things come to a head when doctors advise an Elisa test for her mother and she begins to suspect her father of being responsible for having infected her mother with ‘the’ dreaded disease.

This is the rare film that shows a father financially dependent on the daughter. How that impacts the interactions between the two while also placing the father in the position of a caregiver is what gives the film its emotional heft. Some of the film’s most tense sequences play out between the two at the dining table, as they tiptoe around the subject of money required for the mother’s treatment. At the same time, as the electricity goes off in the middle of dinner, and Rohini cries out to her father, you realise with a start that children probably never grow up, that they will probably always need their fathers. In the film’s closing sequences, as the lights go off again, and Rohini cries out ‘Baba’, you hear her father’s calm voice from the other room: ‘Aami alo niye aschhi.’ (Let me get the light for you.) No one could have put what a father signifies better.

Saanjhbatir Rupkathara (2002)

Though not as accomplished as the other films on this list – primarily because of its rather stilted dialogues and propensity to overstate every emotion – this film by Anjan Das offers a rather unique perspective on the father–daughter relationship. Saanjhbati, so named because she was born at twilight, has a close bond with her painter father (Soumitra Chatterjee again). The father makes a painting of his daughter every year on her birthday and she grows up idolising him, turning to him for answers to the many issues that vex her in her journey to womanhood. She calls him ‘gaach’, the protective tree that provides her the shade. She emphasises that even if no one understands her father, she always will.

However, when she and her mother stumble upon her father making love to his student, Deepa, Saanjhbati’s world comes crashing down. Her mother dies of shock and she cannot bring herself to forgive her father. Years later, she learns that her father had not painted since that day. She meets Deepa who offers Saanjhbati a new perspective to what she sees as her father’s betrayal, thus paving the way for a reconciliation.

Kaalpurush (2005)

Buddhadeb Dasgupta’s characteristic abstract take on memories provides yet another memorable father–son duo in Bengali cinema. Sumanta’s (Rahul Bose) life is coming apart. His wife is seeking to break free of her domestic confinement and has been involved in an extramarital affair. She even tells Sumanta that he is not the father of their children. Professionally, too, he is in the doldrums. Coping with the vagaries of life, he seeks solace in memory. Estranged from his father for years, he suddenly yearns to bridge the chasm. A surreal chain of events that defies notions of space and time bring together father and son who relive the past – Sumanta’s anguished childhood as his mother, pained by his father’s betrayal, leaves his father who becomes a vagabond, abandoning Sumanta to his scars.

Even as he struggles with the present, Sumanta’s ‘interactions’ with his father – are they real or are they a figment of his sensitive mind? – become a means of addressing old wounds. Rarely has the father–son dynamic been as poetic and yet as full of anguish as in this non-linear cinematic universe that Dasgupta creates, conveying the fragmented nature of memories, and the essence of this most difficult of relationships.

Podokkhep (2006)

Though essentially a film that addresses the loneliness of old age and how one becomes more and more childlike with age, at the heart of Suman Ghosh’s debut is the relationship between a father (Shashanka, Soumitra Chatterjee in the role that eventually fetched the actor his first National Award as best actor) and daughter Megha (Nandita Das). The interactions between the two are informed by a rare understanding of the dynamics that animate this bond. She admonishes him for nicking his cheek once again while shaving. It reverberates in his mind as a voiceover of the ‘child’ Megha as he stares vacantly at the leisurely rotating ceiling fan when it is time for his afternoon nap. It’s a moment filled with the indescribable loss of realising that one’s children have grown up and moved on.

It is this that lends such poignancy to the way he reaches out to five-year-old Trisha. As he holds Trisha by the hand and escorts her to school, as he watches the cacophony of children at play from its gate, as he takes her on a day-long outing, one can sense the heart-breaking desire to live all over again a time forever lost. Later, after a close friend has passed away, as the father and daughter pore over a photo album, one is again overwhelmed by what the sequence conveys – the futility of trying to hold on to lost time. But not all is melancholy. These despondent bits are leavened by the sparring they indulge in – he insists on putting up a rather second-rate painting on the wall to the chagrin of his daughter – presenting a delectable portrait of the world of a father and daughter.

Cinemawala (2016)

Kaushik Ganguly’s haunting eulogy for the single-screen cinema, a mournful dirge to celluloid with the coming of digital, provides a masterful portrayal of the equation between a father and son. Pranabendu (Paran Bandyopadhyay) is a wholesale trader in fish who owns a cinema hall named after his wife Kamalini. With the advent of digital technology, the hall lies decrepit and abandoned, but he holds on to it (much like the patriarch in Jalsaghar who does not see the writing on the wall). His son Prakash (Parambrata Chattopadhyay) is chafing at the bit to break free of his father’s fish trade (he derisively calls his father a maachwala or fishmonger) and starting his own business. To his father’s shame, Prakash deals in pirated CDs and DVDs of new films – something that Pranabendu considers not only illegal but also something that is sounding the death knell for cinema. As Prakash’s business scheme to screen new blockbusters in a DVD projector system at the local fair becomes a huge success, the battle lines between father and son are clearly drawn.

What makes the film work is the total absence of sentimentality. The son remains unmoved by his father’s plight and has no sympathy even when the father is forced to sell off the projectors in the theatre. Ironically enough, the son follows in the tradition of the father. Pranabendu had himself gone against his father’s wishes to build the theatre and follow his passion for cinema (though, unlike Prakash, he did not turn his back on fishing, preferring instead to explain the nuances of cinema to his father by providing a delightful equivalence between the two worlds – the producer’s pond in which the director casts his net to come up with a good catch which he delivers to the distributor at wholesale rates who passes it on to the exhibitor). Such nuances are lost on Prakash. However, he too cannot move out of the shadow of his father’s cinema business entirely, though he finds his own way to conduct it.

In a telling sequence, when Pranabendu learns that Prakash is going to be a father soon, he gleefully tells his Man Friday, Hari, ‘Chhele amaar baba hochhe.’ My son is going to be a father. Implying that soon he will understand what it takes to be one. Nothing underlines the cycle of prickly relationships between father and son, forever fraught, often loving, forever evolving, often doomed.

Mayurakshi (2017)

‘When you are young, you have a world around you. My world has shrunk into a tunnel. Now, there’s only you. Why do I need additional memory?’ Eighty-four-year-old Sushovan Ray Chaudhuri (Soumitra Chatterjee once again), once a brilliant professor of history, now suffering from age-related neurological problems including dementia and cognitive dysfunction, does not understand what the fuss is all about around the many tests and the impending hospitalisation he is being subjected to. His son Aryanil (Prosenjeet Chatterjee), who is going through personal issues of his own, has returned from the US to look after his ailing father. When the father asks the son, ‘Are you sending me somewhere?’, the fear in his eyes, the helplessness of his condition is enough to melt the hardest of hearts.

Aryanil is sensitive, understands his father’s need for companionship – there’s a delectable sequence in a coffee shop that gives an idea of how his presence rejuvenates his father. Watching a teenage couple outside the café, Sushovan insists that certain moments in life need background music. A music track comes on, to which Sushovan enacts playing the violin. Once the ‘performance’ is over, he bends down and keeps something on the floor. Aryanil is befuddled as there is nothing in Sushovan’s hand. Reacting to Aryanil’s confusion, his father says, ‘Violin ta namiye rakhlam.’ (I was keeping the violin down.) One of the great father–son moments in cinema.

However, Aryanil also knows that he cannot afford to stay on. There’s a life waiting for him in the US. And he has to break both their hearts and leave. ‘Bhule jash na’ (Don’t forget me), Sushovan tells his son, his voice quivering. ‘Bhulbo na,’ (I won’t forget), his son promises. Neither will the viewer.

Uma (2018)

Srijit Mukherji’s uplifting drama is inspired by the true story of Evan Leversage and the people of St George in Ontario, Canada, who came together to celebrate an early Christmas for the boy the doctors feared would not live till December. In what is without doubt the director’s tenderest film to date, Srijit takes on the onerous task of replacing Christmas in a small Canadian town with Durga Puja in Kolkata, that too one that needs to be held in March/April and not October.

Himadri’s (Jisshu Sengupta) daughter Uma is terminally ill and expresses her desire to participate in Durga Puja festivities in Kolkata (they are residents of Switzerland and she has never seen a Kolkata puja live). If creating a ‘make-believe’ Christmas in a small town in Canada sounds the stuff of miracles, conjuring a Durga puja in Kolkata, that too out of season, probably lies in the realms of the absurd or the foolhardy.

However, one has not reckoned with the filmmaker’s ingenuity as he proceeds to create his own miracle with the help of a wonderful cast of characters – the production guy Gobindo (Rurdranil Ghosh), the washed-out filmmaker (Anjan Dutt), and the antagonistic Mohitosh Sur (Anirban Bhattacharya). Unabashedly sentimental and yet irresistible, Srijit’s ode to the father benefits immensely from the casting of real-life father–daughter duo Jisshu and Sara Sengupta (as Uma). ‘You have seen fathers like me in films,’ Himadri says at one point to Gobindo. Not quite. Few filmi fathers go to the lengths or pull off what Himadri does for his daughter in Uma.

(Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri is a film and music buff, editor, publisher, film critic and writer)