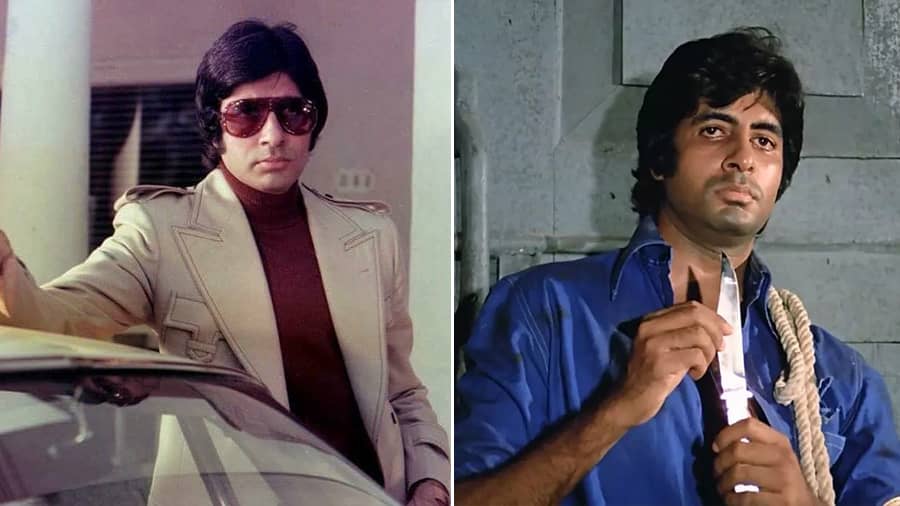

It has been an abiding regret with me that I was not old enough in the 1970s – the decade Amitabh Bachchan ruled the world of Hindi cinema – to understand the magnitude of the Big B phenomenon, to be part of the crowd that thronged his films. In 1979, when India Today termed him the ‘one man industry’, I was barely 10 years old and having recently arrived in New Delhi from a small township in Assam, I hadn’t even heard of India Today.

Again in 1982-83, when he hit a purple patch with the success of Khuddaar, Namak Halaal and Coolie, I was in Shillong, where films came a long time after their release all over the country. I had just an inkling of the kind of hysteria he could generate during his battle for life after the accident on the sets of Coolie. An elderly lady who lived next door came over to our place every day on her way back from the temple and, with tears in her eyes, would tell my mother about having offered prayers for Bachchan’s recovery.

I discovered Bachchan in 1984, the year Big B took a sabbatical from films to join politics at the behest of Rajiv Gandhi. Cable TV was still unheard of and Doordarshan was the only avenue for films on television. Bachchan’s films were few and far between, often limited to only one film in the entire year. So when Faraar was shown on TV it was celebration time as was the rare Bachchan song aired on Chitrahaar.

During this period, Bachchan’s absence from tinsel town, the video boom and a string of big-budget multi-starrers which bombed at the box office made a host of theatres opt for re-releasing old Bachchan films. And most of these films – Mr Natwarlal, Shaan – went on to do better business than the new releases. Theatre owners opted for a strategy of releasing his well-known films in the main shows while the morning shows were generally reserved for his smaller, relatively untalked-of films.

Deewar: Aaj khush toh bahut hogey tum; Trishul: Aur aap mere naajayaz baap

At 16, I was probably just the right age to appreciate the angst of Deewaar, Trishul and Zanjeer and I often returned home with an anger directed at all forms of authority, carefully cultivating an image of a wronged loner. Even as a lonesome Vijay kicked a can around on the beach in Shakti, I did that on my solitary wanderings.

My poor father must have wondered how he had wronged me when my attitude towards him changed after I watched Trishul. I just could not get ‘Main uss Shanti ka beta hoon, Mr R.K. Gupta… aur aap mere naajayaz baap hain’ out of my head (though my mother was very much alive and had not been wronged by my father in any way).

I might have even considered having ‘Mera baap chor hai’ tattooed on my arm! And my grandmother could never get me to visit a temple. For the longest time I could not walk past one without muttering, ‘Aaj khush toh bahut hogey tum’. Till one day my grandmother declared, ‘Chhamra tar maatha khachhe ei lokta.’ (There’s no way I can translate that to get the exasperated essence of that, but roughly: This man [Amitabh Bachchan] will be the ruin of the boy). How she, by the time she passed away years later, had become a die-hard Bachchan fan is a story for another day.

The way he said ‘Sakhi’ in Bemisaal; the drunken scene in Do Anjaane

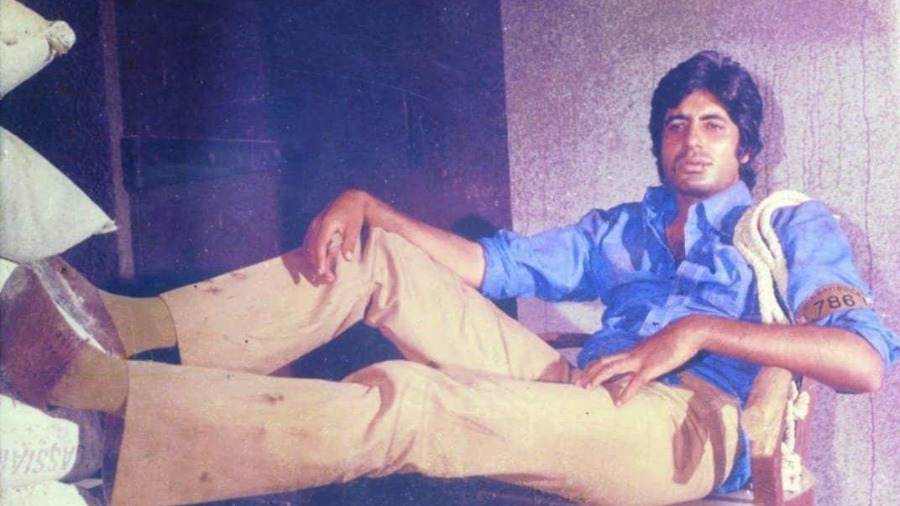

At the same time, the morning shows screening films like Manzil, Do Anjaane, Mili, Benaam, Bandhe Haath, and Saudagar revealed a different facet to the actor. His Everyman roles in these films made him seem like a close relative, a benevolent young uncle rather than the superstar he was.

A little older and in the throes of life’s first crush I watched Muqaddar Ka Sikandar and my starry eyes, on the verge of tears, discerned in his unrequited longing for his beloved ‘memsaab’ my own story of floundering amorous yearnings. Or for that matter as he called out ‘Sakhi’ to Rakhee in Bemisaal, in an unforgettable intonation, he launched my own adolescent search for someone I could call by the name. People who swear by films like Deewaar and Zanjeer as his finest performances and generally run down his ability as a romantic lead do him a great injustice.

Bemisaal is, for me, his most accomplished performance for the sheer complexity of the role, with its shades of the lover, the loner, the gregarious flirt and yes, probably the most subtle representation (along with Alaap) of his ubiquitous ‘angry young man’. One only needs to look closely at his ‘smaller’ films to get an idea of the range he is capable of. The repentant playboy of Jurmana, the husband in Do Anjaane and the tumour-afflicted fugitive in Majboor are veritable showcases of his range as an actor. Not that any actor who delivers films as diverse as Deewaar, Kabhi Kabhie and Amar Akbar Anthony in three consecutive years needed any proof. Ask anyone about his memorable drunk sequences, and chances are that people will mention Amar Akbar Anthony, Satte Pe Satta or even Hum – there was of course Sharaabi too – but if you ask me, the sequence in Do Anjaane stands heads and shoulders above these.

He did not rave and rant; his eyes sufficed and his baritone did the rest

What endeared me most to Bachchan of these films was the fact that he so eloquently conveyed emotions without ever seeming to try. He did not have to rave and rant to convey his anger. His eyes sufficed and his baritone would do the rest. A case in point is the scene in Kala Patthar where he confronts a thug (Sharat Saxena) who brandishes a knife. Bachchan simply looks at him and intones deadpan, ‘Tu to gaya, Dhanna.’ (You are a goner, Dhanna.) And you knew the man has had it. And if he was the larger-than-life entertainer in the Manmohan Desai films, he punctuated these with the man-next-door roles in the films by Hrishikesh Mukherjee. The star and the actor working in tandem.

Those were the days when Bachchan was relatively inaccessible to the media. Information on the man and the star was not forthcoming. But all this was to change, and I am yet to understand if the change was for the better. As he began to feel the heat following the suspicions of his involvement in the Bofors tangle, he opened up to the media. To my delight, film magazines fell over each other in coming out with ‘specials’ on the man and the star.

As long as I had Bachchan and his films, everything else was dispensable

For the first time, I had access to the fact that in the 11 years since 1973, when Zanjeer was released, only three of his films (Alaap, Imaan Dharam and Faraar) had failed to recover their investments. Films like Shaan and The Great Gambler which were written off as flops at the time of their initial release, went on to become successful when re-released. In fact, some of his films made more money on re-releases than many a hit film starring other actors.

It delighted me to learn that of the 15 top grossers in the history (at that time) of Hindi films, as many as six starred Bachchan in the lead. And it seemed a matter of personal pride to know that in a particularly golden streak in 1978, five of his films – Muqaddar Ka Sikandar, Trishul, Don, Kasme Vaade and Ganga Ki Saugandh – were released in the span of two months and each went on to become a jubilee hit.

Armed with the facts and figures of the box-office performances of his films, the stories of his legendary professionalism, I would slug it out with any friend and acquaintance who dared cast an aspersion on the man or his stardom. The mid-1980s were a period when stars like Mithun Chakraborty, Sunny Deol and Anil Kapoor had started to make their presence felt. A number of my friends were shifting allegiance to these stars, and would needle me with stories of the successes of their films. However, as far as I was concerned, they were merely pretenders.

With the data I had on me I inevitably came out trumps. When they talked about the poor quality of some of his films (Mard), I only had to point out his rare charisma which catapulted some real clangers to box-office glory. It helped that Geraftaar, which released at the time, smashed the box office despite his billing as a ‘special appearance’. And when people carped about his financial duds like Alaap, I always had the trump card of his performance which no one could argue about.

That invariably brought people to talk about his involvement in Bofors which I pooh-poohed. I lost a few friends in the bargain. I took any slight on Bachchan personally, and would fight and sever ties with anyone who dared to question his stature or compare any of the wannabe newbies with him. But as long as I had Bachchan and his films, everything else was dispensable.

Shahenshah: the first chink in my blind devotion

Shahenshah marked his return to films post-politics. It also marked the first chink in my blind devotion. The media had gone to town with the impending release. The hype was overwhelming with reports of Bachchan himself being so impressed with the film that he had seen it close to 70 times. The radio promos with Kishore Kumar belting out ‘Andheri raaton mein’ sent a chill down my spine. The advance bookings were threatening to turn film theatres into veritable war zones. I would visit theatres simply to partake of the thrill of seeing lines of ticket seekers snaking a mile and more.

So when I saw the film, my first taste of the Bachchan draw in live (I had seen Kaalia, Satte Pe Satta and Desh Premee in the theatres when they had released in 1981-82, but it was my father who had purchased the tickets), I was filled with a disappointment I could not account for. His next films did nothing to assuage the sense of being let down. In fact there was probably no sight more tragic (discounting the abominable ‘Mere angne mein’ in Laawaris) than Bachchan on screen with a crocodile on his back in Ganga Jamuna Saraswati, as though saddled with déjà vu. For the first time I could not come up with arguments to counter those who were beginning to write him off. I felt betrayed, as though Bachchan owed me a better deal personally.

I wonder whether I had grown up or whether his films had become smaller

I wonder whether I had grown up or whether his films had become smaller. Because none of his films in this phase came remotely close to my expectations and the hype they generated. There were the odd sparks in Agneepath and Main Azaad Hoon but something had gone missing. His return after another five-year break following his misadventures with ABCL and beauty contests was even more disappointing.

Somewhere down the line he seemed to have lost that endearing connectivity. The entertainer had overtaken the actor. In his post brand-entity image, he may have become more accessible to the media, with interviews and promotions dime a dozen, but paradoxically for me he seemed to have become inaccessible and distant.

His performances, particularly the anger, seemed forced

His performances, particularly the anger, seemed forced and in contrast to the subtlety of the past, was loud and jarring. Major Saab is a major case in point where he simply barked out a one-note performance devoid of any vocal nuances. Or Khuda Gawah for that matter, the first Bachchan film I left midway through because I simply could not take the loudness (there was this pronounced ‘hainn’ that had entered his dialogue delivery which grated), let alone the loopholes in the script through which entire battalions could pass. And what could have been sadder than watching him try to outpace Govinda in Bade Mian Chote Mian. Or being a pale shadow of himself trying to match Daler Mahendi in ‘Na na na na na re’ in Mrityudaata. But my falling out of Bachchan fandom is a piece for another day.

In his avataar as a TV game show host, he rediscovered his touch, his ability to connect with the masses. He reinvented himself. Unlike those who made rather uncharitable comments about his fling with television and his endorsement of every conceivable product, I had nothing against that. He was a performer and it was a job that paid him well. If we as individuals are free to take up work we like, there was no reason why Bachchan should be judged any differently.

Yes, he was brilliant in Khakee and Dev, Nishabd and Eklavya, but….

For me what counted was the kind of films he delivered and that is what disappointed with unfailing regularity. To say that he is the strong point or the only good thing in mediocrities like Mohabbatein or the puerile Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham and Kabhi Alvida Na Kehna is a hoary cliché. He is the strong point of any film he acts in. Period.

Yes, he was brilliant in Khakee and Dev, Nishabd and Eklavya, but there was something about him in films like Cheeni Kum and Paa, Pink and 102 Not Out (just watch Rishi Kapoor closely in this and you would know what I am saying), all rather celebrated, that I found jarring, that did not quite seem organic. I am not sure if the younger directors are too much in awe of him to rein him in, or that he had bought into his legend as the greatest of actors, but there is in these films a subtle playing to the gallery that takes away from his performances.

Walk down Mili memory lane

Watching Mili in the theatres a couple of days ago, as part of Amitabh Bachchan’s 80th birthday celebrations, with Jaya Bhaduri attending the screening, took me down a road I have not visited in ages. It’s almost four decades now since Amitabh Bachchan first held me spellbound and I realise that the spell is a lot weaker than it was then. I know it will never be the same again. That is the price one pays for growing up, I guess. The last line of Rainer Rilke’s poem ‘Fears’ – ‘growing older has served no purpose at all’ – could well have been written for what I experienced watching Mili. Though I know that it will never be, I would give anything to have restored in my heart what once was.

That ultimately I think is the magic called Amitabh Bachchan.

Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri is a film and music buff, editor, publisher, film critic and writer