What is it about monsoon that fascinates Calcutta so much? Traffic comes to a standstill, streets and lanes become waterlogged, plans you made with friends often go for a toss and we often face blackouts after a heavy downpour. Then where does this obsession, this unpragmatic romanticism attached to Calcutta’s monsoons stem from? Is it because the arrival of monsoon signals the start of hilsa season, and we all know how much Calcutta loves its “ilish maachh”. Or is it because of the countless number of songs that have stated how love blossoms abundantly during this season?

I know who the culprit is, it’s cinema. Of course, for generations we have learnt of love and romance from our films. If it’s raining and you find yourself and your beloved together, if you have somehow rushed to a shelter, if both of you are drenched and there is nobody else around, by all means break into an impromptu ball dance routine. SRK and Kajol made it work, why can’t you? Also, the movies make it seem so romantic to sip piping hot tea from a small clay cup while also getting drenched in the rain, so it must be the idea for a perfect date, never mind the fact that if you actually try it, your tea won’t be piping hot for very long. Hell, it will stop being tea about three seconds after you step into the rain.

While we are at it, we might as well stretch our arms, look up and let it pour on us. What’s the point of calling Shawshank Redemption your favourite film if you couldn’t even imitate Tim Robbins’s famous pose from the poster? Cinema has spoilt us, I tell you, and it’s because of this obsession that cinema itself started, that those involved with performing in or making films now have to recreate these unrealistic rain sequences in order to quench the audience’s thirst.

But have you ever wondered whether the rains that look so romantic or look like so much fun on screen are as much fun to recreate? Okay, let me draw on my own experiences of shooting rain sequences to answer that question.

Funnily enough though, actual rain and shoot schedules are sworn enemies. It’s understandable then that most units tend to avoid planning outdoor shoots in monsoon. Sometimes, if it’s a particularly heavy downpour, even indoor shoots might need to be cancelled because of safety concerns. Which is why, with the exception of a few films or shows, almost all the rain that we see on screen is created in a controlled environment with rain machines, power hoses, water tankers. Alright, now that being “Captain Obvious” is done, let me get down to the job at hand. Rain sequences, worth the effort? Not? Let’s see. In the recent past I’ve had the opportunities of performing two such sequences. Let’s analyse both.

Shabash Feluda

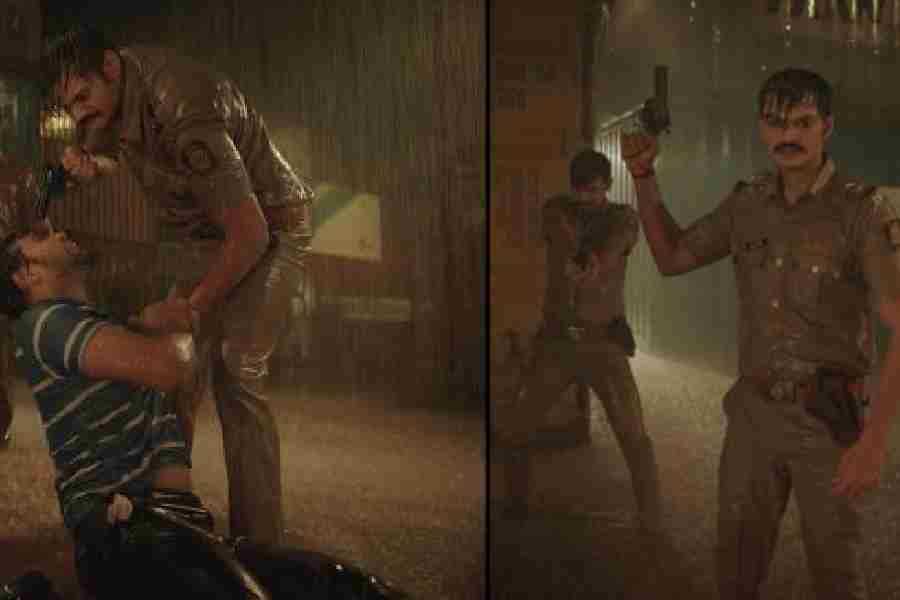

Most recently, I performed a foot chase through a dockyard, in the rain, for Arindam Sil’s Shabash Feluda. Ganesh Gaitonde, the character that I play, a police officer investigating a drug racket is in pursuit of two criminals involved in the racket and the chase leads to a dockyard. The production designer Riddhie Basak recreated the Mumbai docks right here in Kidderpore. Furthermore, he waterlogged the entire setup. Mostly the water was ankle deep, in certain spots it was knee deep. This space was surrounded by piled-up shipping containers, each container about 10 to 12 feet in height.

The chase was choreographed to start at ground level... then we climb up to a makeshift ramp on top of the containers at the height of about two stories, from where we were supposed to jump down from the second level to the first, then onto a truck, and then from the truck back on ground. The chase ends shortly after that with Gaitonde and his team surrounding the criminals. Sounds simple enough, right? Well it wasn’t, as we discovered once the action rehearsals started.

The containers that looked like solid metal are actually designed to bend in order to withstand the perils of sea. So, with every stomp of our running feet, the metal beneath us sank down and then pushed back up, making us extra cautious about our stepping. Ironically, climbing up to the top level wasn’t the difficult part, the difficult part was jumping down levels. Each level was about 10 to 12 feet, as mentioned before.

But the problem was that we were shooting a chase sequence. We didn’t have the luxury of stopping and then sliding down timidly, all of it had to be frantic and chaotic. The jumps had to be precise, we had to follow a certain technique otherwise we could injure our knees, our spine. Bend forward too much and you risked crashing your face against your knees, lean back and you might cause your knees to hyper extend or worse, you could lose footing, fall back and hit the back of your head. We didn’t have the space required to roll after jumping, no harnesses either. Which is why these rehearsals are important.

The professional stuntmen I was working with that night, led by Aejaz Sheikh, had over 400 films under their belt. I knew I’d be safe as long as I follow their instructions. So for the first hour or so, we just rehearsed the entire set-piece. Once we were ready to roll, however, we realised we hadn’t factored in one essential component — the rain. The rehearsals were on dry surface, that changed now with the rain machine coming to life.

For the next three hours, we performed the same routine over and over again, different angles were captured, inserts were shot, alternate options created. We must have made that set of three jumps over 10 times in that period, with every shot the body kept getting tired. The wet metal was perilous to run on, even more dangerous to jump onto. The spot on the ground we were jumping onto from the truck had begun sinking in. We shot for almost four hours, if not more, for a sequence that’s in the show for about five minutes. By the time we finished the action shoot, I had fallen several times, had cuts and bruises. The worst of it: at some point, probably during one of the jumps, I had hyper extended my knee. The next day, I couldn’t even stand without help, let alone walk.

REKKA

The other rain sequence I want to talk about was not an action sequence as such, but it was a violent one nevertheless. This was for Srijit Mukherji’s Rabindranath Ekhane Kawkhono Khete Ashenni. Now, I cannot really discuss what happens in the scene itself, on the off chance that someone hasn’t watched the series yet... wouldn’t want to give away spoilers. However, in the scene, my character Phalu crosses a point of no return. It’s a vital plot point. The scene was being shot in Nepalgunge, an area surprisingly close to Tollygunge that mostly has small farm lands, ponds and lakes.

We were shooting this rain sequence in the last week of December, 2020, on one of the coldest nights of that winter. Back then, we were still living in fear of the coronavirus. All shoots were being done following strict protocols, regular testing was mandatory. Whether one would admit or not, after the year that we had all had, shooting with a big unit, with lots of people around was still a concept that made us somewhat uncomfortable. For obvious reasons, as actors we couldn’t shoot with masks on. Given this set of circumstances, I had been informed right at the onset that I would be required to shoot a rain sequence in the middle of winter and I had consented to it.

However, now that the hour was upon us, I was extremely nervous. My primary concern was falling sick. It would mean a compromised immune system and perhaps even two weeks of isolation, if not worse. Usually, in such a situation, actors use brandy or rum to keep themselves warm. Being a lifelong teetotaler, I didn’t have that option. So I opted for the next best thing. I requested the production to keep supplying me with a mixture of warm milk and honey. The location was set up. We were shooting next to a small pond. The location had been beautifully lit up by our DoP Indranath Marick and his team.

I was called to the spot a little before midnight. As soon as I stepped out of my vanity van, the winter made its presence felt. I checked the temperature on my phone — 11 degrees. Could be worse… I thought to myself. The rest of them will be shooting at zero point in near freezing temperatures. The thought gave me some resolve, if they can, I can.

I went into my usual pre-shot routine and concentrated on the job at hand. Our director Srijitda, the entire directorial team, the make-up team, the production assistants with milk and honey in hand, the costume department with dry towels, everyone was where we’d be shooting, as close to the actors as they could possibly be without getting into the shot. This show of solidarity gave me more confidence. Srijitda explained the shot to us and we got ready. Somnathda, our make-up magician, suggested we get drenched well before it’s time to roll. Rightly, so it would give our bodies more time to adjust to the cold.

The rain machine was turned on and the flow of water hit us. It felt like thousands of sharp needles pricked us simultaneously. Right after came the first dose of milk and honey. And then it was time to roll. We shot the entire scene in just over an hour. Milk, honey and dry towels kept coming. Srijitda, his associate Abhrajit, in fact everyone around us kept enquiring if we are okay. We actually were. The warmth the entire unit showed, the way me and my co-actor were looked after, ensured we could perform without a worry in the world.

Now, back to the question at hand. Was it worth it? Well, in all honesty, it was. On both occasions, when I watched those scenes, I felt very proud of having been a part of what I saw on screen. There’s just something about rain sequences, I admit. Those classic rain sequences that have become iconic to us could all perhaps been done without the rain, or at least some of them. But then they might not have gone on to become iconic.

The way light is refracted through water, the way it bounces off ponds and puddles or even the soundscape that is used, all of it comes together to create magic. There is a reason why the masters have used rain as a metaphor, used nature as a character or even used rain to set a certain mood for their film. It’s not just rain, never just rain. Of course, I am yet to “romance” in the rain so there’s still an integral part of the magic of rain on screen that I am yet to experience as an actor.

As for Calcutta’s love affair with monsoon, well, yes. Traffic does come to a standstill, but it gives us a chance to stop staring at the rear bumper of the car in front of us and instead look around at the happy smiling faces of people getting drenched in the rain, trying to wash away their worries; it gives us time to look at the city through water droplets and magical colours, like we’ve never seen it before. Streets and lanes do get waterlogged but then hasn’t it been far too long since you sailed a paper boat? Occasionally, if there is a heavy downpour, we do face blackouts and we do have to cancel our plans of going out, but when was the last time you had the chance to have a candlelit dinner with your parents while the raindrops performed a concerto on your window panes? It’s that time of the year again. Keep your flip-flops ready, relearn how to make a paper boat, be prepared to cancel a few plans and get working on a “monsoon movie marathon” list right away.

Debopriyo in Shabash Feluda