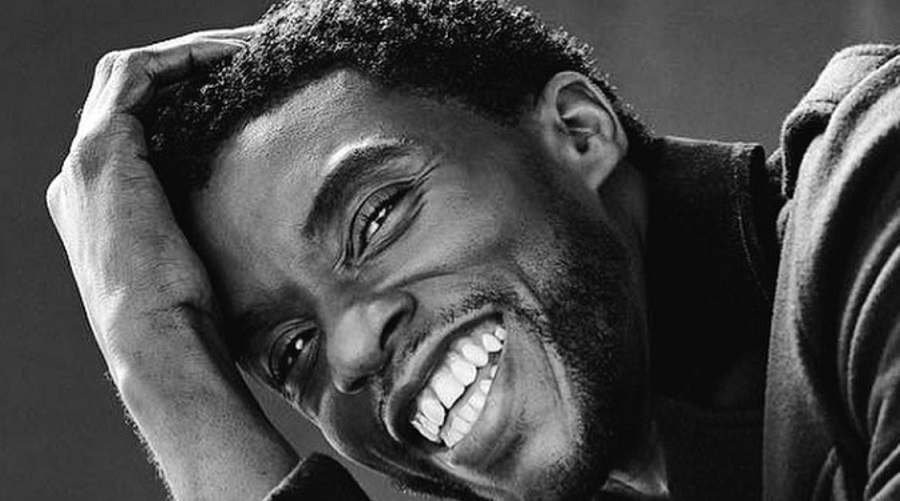

Chadwick Boseman was posthumously honoured with a Golden Golden for his performance as the strong-willed trumpet player Levee who marches to his own beat in the musical period drama "Ma Rainey's Black Bottom", the actor's swansong.

Boseman, who died in August at the age of 43 following a four year-long private battle with colon cancer, won the award in the best performance by an actor in a motion picture category.

Boseman's wife, Simone Ledward, accepted the award on his behalf in a Zoom call.

"He would thank God. He would thank his parents. He would thank his ancestors for their guidance and their sacrifices," an emotional Ledward said.

It's the first Golden Globe win for Boseman, who achieved global stardom as King T'Challa of fictitious African country Wakanda aka superhero Black Panther in the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

Much before 2018's "Black Panther", the actor had made a name for himself by playing iconic black historical figures like baseball star Jackie Robinson in "42", singer-songwriter James Brown in "Get on Up" and the first African-American Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall in "Marshall".

Anya Taylor-Joy at the award ceremony. Twitter/@anyafiles

With the pandemic raging, the award ceremony was nothing like other years.

There is now one more way in which the stars are just like us. They too, sit at home, drink through teleconferences and endure technical glitches.

Immediately after Laura Dern announced Daniel Kaluuya as best motion-picture supporting actor, the night’s first winner appeared on the screen and began speaking. But his voice was missing. The producers cut away and Dern apologized. At the last second, Kaluuya reappeared, excitedly saying, “You’re doing me dirty! Is this on?”

Having the Black winner of the first award inadvertently silenced encapsulated two challenges of these strange, troubled Globes: the production issues of putting on a show in the midst of a deadly pandemic, and the fallout over the lack of Black artists among the nominees and Black journalists among the award-giving body, the Hollywood Foreign Press Association.

The Globes handled the first clunkily but with occasional charm. It handled the second incompletely and even more awkwardly.

The oddity began before the awards. E! and NBC held “red carpet” preshows that had no red carpet. Scratch that — there was only red carpet, with the sashays of celebrities replaced by hosts doing remote interviews outside a quiet Beverly Hilton.

Chadwick Boseman's wife, Taylor Simone Ledward, accepts his Golden Globes 2021 win. Twitter/@Variety

Best director nominee Regina King, in a striking metallic dress, was joined by her dog, lounging on a canine bed behind her. Stars’ shelves were artfully arranged, their backgrounds pleasingly blurred. It was a preshow made for Room Rater as much as the Fashion Police.

The show proper kicked off with co-hosts Tina Fey and Amy Poehler, who from 2013 to 2015 made hosting the Globes look easy, bringing an easy rapport, snark and cheer to each ceremony they did together.

The key word being “together.” This time they were socially distanced by a full continent, Fey in New York, Poehler in Los Angeles, split-screened together as they played to small crowds of masked essential workers. Their routine leaned into the weirdness — Fey mimed reaching out to stroke Poehler’s hair as someone else’s arm finished the job at the Hilton.

Their long-distance duologue was surprisingly tight, if not especially cutting. (They did a little on the HFPA’s diversity problem, a lot on how much TV and film we streamed this year.) But it set a tone: Things won’t be the same, but this year, what is?

There were some benefits to the virtual gallery of stars. No one had to spend awkwardly long navigating to the podium from the back of a ballroom. It was charming to Jason Sudeikis rocking a tie-dye hoodie, and winners sharing the moment with their kids instead of telling good night from the stage.

Accepting as best actress in a TV musical or comedy for “Schitt’s Creek,” Catherine O’Hara pretended to be interrupted by play-off music blaring from a phone. In one of the few in-person segments, Maya Rudolph and Kenan Thompson simulated an off-the-rails in-person acceptance speech. And the tearful acceptance on behalf of Chadwick Boseman by his widow, Taylor Simone Ledward, would be memorable in any year.

But like a lot of our mediated experiences over the past year, the night begged to be rated on a curve. It was more often fun in a “Good for them for giving it a shot” way. (The sketch with medical professionals giving celebrities telehealth advice? We have already asked too much of essential workers this year.)

Even with living-room champagne, teleconferencing is still teleconferencing. We’ve spent a year staring at celebrities on screens. Spending a night watching them stare at each other, in the excruciating precommercial multiscreen hangouts, is not quite a fabulous escape. We get enough disjointed Zooms at work and school. (Alas, we cannot play those off when they run long.)

There was only so much the Globes could do about the global circumstances. How they addressed the local circumstances that the HFPA only has itself to blame for is another matter.

The Globes, usually greeted as a harmless, messy goof, were serious news this year for all the wrong reasons. In addition to the diversity uproar, a recent Los Angeles Times investigation of the HFPA found practices that smacked of corruption, including members accepting five-star hotel stays to visit the set of the “Emily in Paris.”

The association acknowledged the racial issue in a perfunctory, we-have-work-to-do statement from the stage. It addressed the self-dealing charges not at all.

The reason the Globes persist is that they’ve become a valuable TV show, bringing an army of celebrities together for NBC under one roof with plenty of cork-popping social lubricant. This year’s show demonstrated what the Globes have when you take that away: not much.

Whether the HFPA will be any healthier in a year is anyone’s guess. Hopefully the world will be. For now, all we had were bittersweet reminders of connection, as when producer Norman Lear accepted the Carol Burnett Award from a solitary room, giving his secret for longevity: “I have never lived alone. I have never laughed alone.”

Connection with other people, he reminded us, is the best medicine. Which was just one reason that this disjointed version of a usually carefree production felt like it was ailing.

With reports from New York Times News Service