Who is the “world’s number one star”?

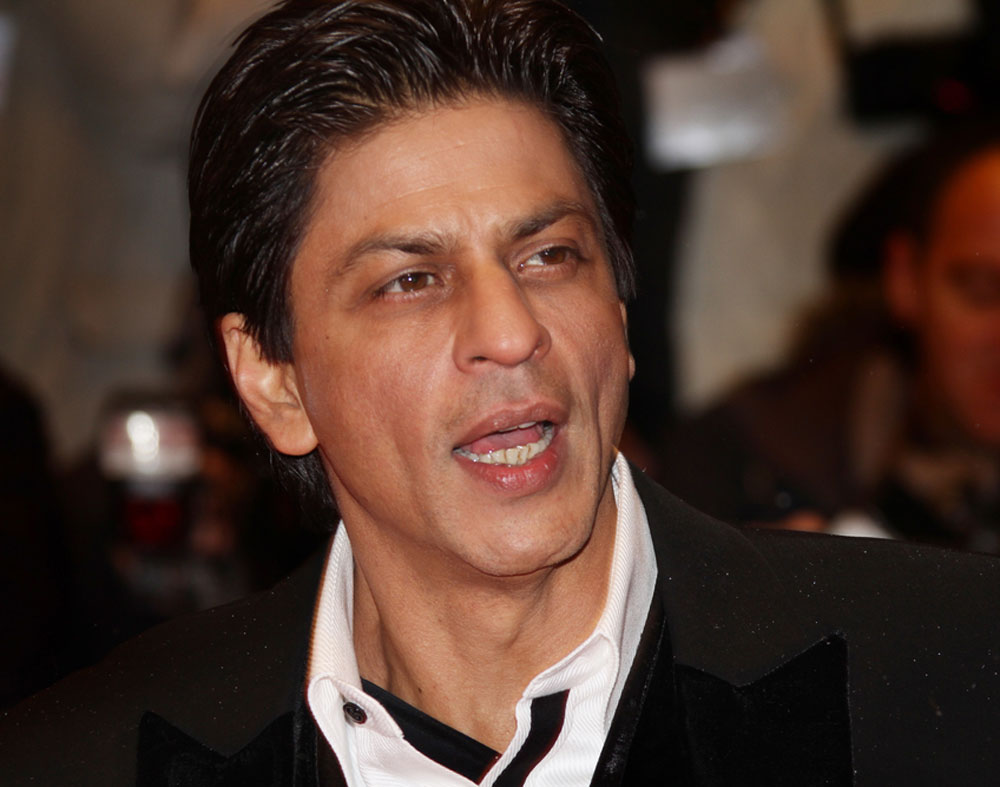

It’s without doubt Shah Rukh Khan, asserts Fatima Bhutto, niece of the late Pakistani Prime Minister, Benazir Bhutto, who has interviewed the actor for her latest book, New Kings of the World: Dispatches from Bollywood, Dizi, and K-Pop (Columbia Global Reports; £11.99). Fatima has written an entertaining 206-page, mini-biography of the Hindi film industry, concluding that when it comes to global influence, Bollywood is giving Hollywood a run for its money.

She tells readers that Shah Rukh “has fans all over the world, including a coterie of eight to ten elderly German ladies who have followed him everywhere he goes for the last twenty years, watching him lovingly from the sidelines”.

She pursues the SRK trail to Peru in South America, of all places, where she watches “a group of teenagers in black leggings dancing to Ishq Shava from Shah Rukh Khan’s Jab Tak Hai Jaan”.

Two girls, Jamyle, 10, and Vanessa, 8, who have “bright pink lipstick smeared across her tiny lips” and who are part of the Dilwale Dance Group, confide that when they dream at night, they dream of Mumbai.

Fatima’s Bollywood journey begins in the dusty lanes of Peshawar, the birth place of Dilip Kumar (born Muhammad Yusuf Khan), Raj Kapoor, and Shah Rukh’s father in pre-Partition India. An old man informs Fatima that Shah Rukh visited Peshawar twice when he was starting out but she suggests another trip is unlikely, “given the political climate across the border in India where the right-wing routinely suspects Muslims of acting as fifth-columnists for Pakistan”.

Fatima makes the most of two days in Dubai where she chats with Shah Rukh at his super-kitsch Palazzo Versace hotel before accompanying him in a Falcon AW 189 helicopter to the desert resort of Qasr Al Sarab where he performs in a nonsensical but hugely popular Middle Eastern TV programme, Ramez Taht El Ard (Ramez Underground).

Over endless cups of coffee, Shah Rukh tells her he has “never been a straight-jacketed, proper hero in my films”.

In Baazigar, for example, he recalls, “I take a girl (Shilpa Shetty) up a terrace and throw her off… I remember when that film released most of the kids were loving it.

“There’s a certain kind of goodness I bring to badness. People trust me with badness. You know, normally people trust you if you’re good. I think there’s an inherent quality that you trust me with badness. You say, it’s okay, if he’s going to be bad, he’s not going to be really bad.”

Fatima Bhutto Picture by Allegra Donn

Fatima makes the point that “Bollywood’s political sensibilities mirrored India’s”. In newly independent India, “the stars of the day, Raj Kapoor, Dilip Kumar and Dev Anand, were all inspired by Nehru’s ideals”, which were “social justice, liberty and fraternity”.

But with economic liberalisation, Bollywood has changed. “The ’90s hero no longer danced in sugarcane fields with farmers but in London’s Trafalgar Square with a gang of miniskirted blondes…..the hero drives a BMW and wears Nikes. His family lives in a mansion — this period is also marked for Bollywood’s narrative turn to Non-Resident Indians (NRIs), whose money and economic agility had bought them homes in the English countryside and penthouse apartments in New York.” Incidentally, Karan Johar did not respond to Fatima’s request for an interview, but she writes: “It was Bollywood, notably the films of the director Karan Johar, that recast the NRI as the epitome of sophisticated modernity, as the masters of global capital and international savoir faire, and it did so at the intersection of two ominous forces: neo-liberalism and Hindutva.”

Fatima analyses some of Shah Rukh’s movies, among them Dilwale Dulhania le Jayenge, Devdas, Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham and My Name Is Khan, one of only six films out of nearly 100 in which he has played a Muslim. “Khan has pointed out that’s a matter of coincidence rather than political posturing…today Khan seems marginalised, or at least viewed with suspicion by India’s increasingly muscular right wing.”

She quotes Shah Rukh that after the 2008 Mumbai massacre, he was asked: “What is your opinion on terrorism?”

His response: “I find that a very strange question, because no one can have a difference of opinion on terrorism.”