One of several ways in which the theatre we are about to enter is singular is that the people have never ever been asked to deliver to the incumbent a mandate so sweeping it would resemble a clean slate likely intended for writing India — Bharat — anew. Abki baar, 400 paar.

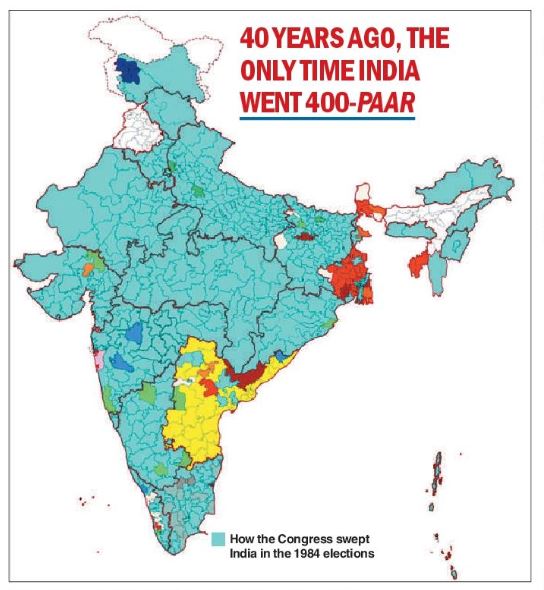

The last and only time one party has secured Brian Lara grades in the Lok Sabha was in 1984, the unintended and widely unforeseen triumph of hope over the insecurities of a shuddered nation. 1984 was a year so cataclysmic it gave truth to the allegory of George Orwell’s undying eponymous classic.

Indira Gandhi sent the army into Amritsar’s Golden Temple, Sikhdom’s holiest shrine, to destroy Bhindranwale’s formidable terror nest. Operation Bluestar did

more than just pulverise the Temple and scar Sikh psyche; it ended in Indira’s assassination months later and triggered the madness of wanton vengeance against the community whose backwash hounds us to this day.

Columns of the army rose in pyrrhic revolt that year.

The sudden loss of a figurehead Prime Minister and a western borderland, from Kashmir down to Rajasthan, suddenly turned vulnerable by operatives across, sparked a migraine in our minds. India felt like it was under siege like never before. Then, on a dark early December’s night, a rotten tanker valve blew at a Union Carbide facility in Bhopal and toxic methyl isocyanate spewed uncontrollably — the worst chemical disaster the world has known. It was confirmation of the curses the nation believed had befallen it.

Such was the setting that gave Rajiv Gandhi 400-plus in the Lok Sabha, an overwhelming empowerment to blow away the apparitions.

Rajiv, swiftly ascended to a darling poster boy of a Prime Minister, put a silver hem to the darkness: he called the verdict his licence to take India into the 21st century.

It may not be entirely misplaced to recall here what happened to 400-paar by 1987. All, or most, of it had gone up in the Bofors smoke.

Call it ambition, call it audacity, Modi’s 400-paar dare — or demand — is no less astonishing for emanating from a Prime Minister seeking a third successive term.

Modi is seeking a repeat of the Rajiv leap with rhetoric of his own minting — as he gives shape to the New India aka Vishwaguru Bharat, he must line the road to the centennial of India’s Independence 23 years down.

Please read into that an essential subscript seldom put out in writing but seldom left to the imagination: it is to be the re-investiture of a high-voltage propaganda-fed cult that seeks to loom over all it surveys, a menhir of a monolith that is at once India’s most insistent political reality and material of popular myth, both raja and rishi, elected chief executive and self-appointed regent of the faith — priest of Ayodhya, bearer of the parliamentary sengol and the unmistakable symbolism that surrounds it.

One of the intractable things about Modi for his political opponents must surely be that he has conjured and become the manifestation of so many descriptions, tangible and intangible.

Rahul Gandhi, his chief adversary, seldom defaults on the necessary articulations for the singular, and mesmerising, diversity India remains. He has consistently intoned the lofty and noble ideas of the Constitution and of the requirements of pluralist India. He has, through the course of his crisscross yatras of India, spoken of the non-negotiable obligations of neutralising the politics of “hatred and bigotry” which he insists Modi and his regime represent. What Rahul, critically, has not cared to do is to give his ideals muscular legs to run on, rebuild the party that has gone amnesiac on how to attain power.

Modi, a matchless and vigorous pulpit communicator, has pushed on with his New India rhetoric whose definition, beyond unapologetic majoritarian ultranationalism, remains a work that Modi reveals as Modi wills. Very often, the Modi design is spelt out in his silences — or his absences. The Modi stylebook is to message his constituency also by what he does not say or do. Illustration: his obdurate refusal to travel to Manipur, a stained metaphor for how prejudice, peddled actively by the state and its instruments, can scald and set people intensely apart.

As the seven-phase 2024 vote approaches, it is hard not to note, and spell out, the imbalance embedded in the contest. It is a narrative of accumulation on one side and depletion on the other.

The Modi-led alliance has shopped and grabbed partners aggressively over past weeks. INDIA has suffered emaciation from where it began; it lost Nitish Kumar in Bihar, it is a non-starter in Bengal and Jammu and Kashmir.

The Modi government has shown little embarrassment in using institutions of state; it has scarcely mattered whether they are under the executive’s direct control or not. The Opposition has suffered targeted chasing and hounding by agencies such as the Enforcement Directorate.

The treasury has lorded over the legislature as never before, often turning to obfuscation and abuse; the Opposition, depleted and divided, has endured record refusal and suspensions.

There can probably be no finer index of how lop-sided the contest is than the revelation of who got what from the electoral bonds. Beyond the bonds too, the Modi project’s access to resources not merely financial is immeasurably greater.

It is beyond astonishment how and where India’s traditional party of power lost the keys to the kingdom, the tricks to acquiring power and holding on to it. It is nothing short of astonishing that they seem not only to have fallen in the hands of the Narendra Modi-Amit Shah enterprise but are also being put to vigorous and profitable use. The swiftness and swag with which they began to manoeuvre and manipulate the handles of power and the divisive social impulses to appropriate advantage after assuming power in 2014 remain a most dramatic, and no less worrisome, work in progress.

What has rolled out in the general elections since is an undeclared open-ended referendum on what the arrival of Narendra Modi in power should really come to mean. The code of these elections needs to be understood beyond the numbers in the Lok Sabha. This is no ordinary time. And the time to come may be even less ordinary. For if there is one thing the last two general elections have done, it is this: validate the values Modi and his worldview embody and vacate the values of several, or all, of his predecessors.

Majoritarian India has never been so audaciously enthroned. The majoritarian ethic has never appeared so unflinching in its determination to impose itself.

Postscript: As you read this, we are two days from the first vote for 2024. Save the orchestrated outings of the chief competitors — and the raucous battlements of television studios — you’d probably have discerned barely a ripple on the landscape of waves our elections usually are. A silence, even sullenness, hangs in the air, an anti-excitement. Nobody can be sure what it is telling us, if anything. Does it tell us of a contest whose outcome there’s no thrill or suspense over? Or is this the silence of a voter intending a surprise? We do not know; we shan’t until June 4. It’s when the people speak and India listens.