THE SHEIKH AND THE MUFTI: Dead men do tell tales. Often vividly and in the fullness of truth for they are no longer held by the fear of consequences.

This is the story of two gravesides — one of a Sheikh, a Kashmiri Leviathan and, to admirer and adversary alike, a leader beyond compare; the other of a Mufti who was able to conjure, with beaver-like persistence, a parallel nativist project in the Valley.

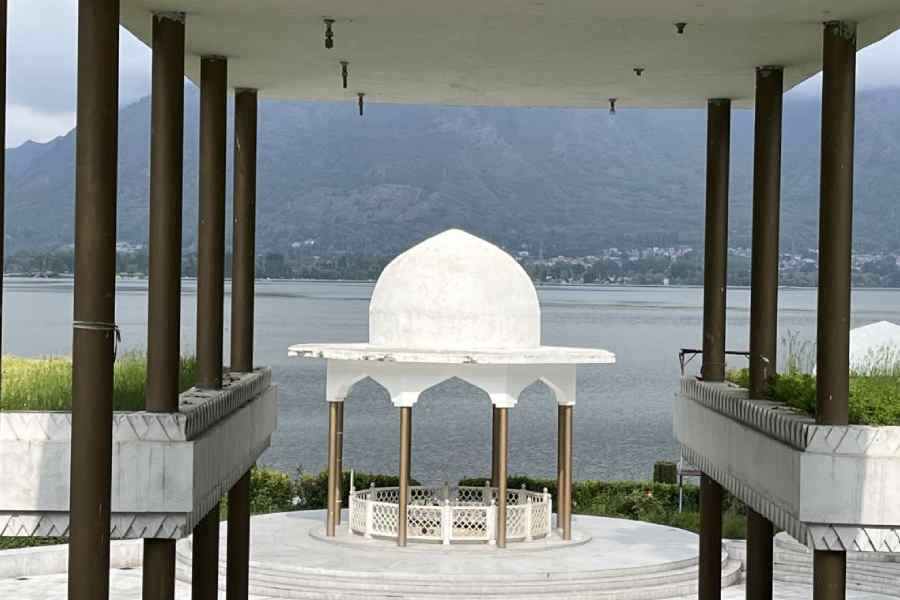

Sheikh Mohammed Abdullah lies interred on a grassy knoll along the western edge of Srinagar’s Dal Lake, within earshot of Hazratbal, the mosque whose construction he inspired and which is vault to the holy relic of the Prophet.

Mufti Mohammed Sayeed rests a little less than a hundred kilometres south of Srinagar in Bijbehara, the mofussil habitation of his birth. His canopy is the shade of magnificent chinars in a Mughalesque garden named after Dara Shikoh.

Both locations restrict access, with padlocked gates and whorls of concertina wires thrown about as additional fencing. Neither possesses the air of a public memorial, as such monuments to the loved and endearing departed often are; neither is welcoming to those who might want to come by and pay respects. Both are, in fact, forbidding of nature, demonstrably out of bounds.

The truth — and perhaps the irony — about the mausoleums of the two most eminent Kashmiri politicians no longer alive is that not many are bothered. Posterity has been cold and hard on both the Sheikh and the Mufti. Once accorded impassioned loyalty and adulation — the Sheikh far more than the Mufti — both lie attended by indifference, buried in blame. Both, in separate ways, belied the visceral Kashmiri aspiration to conduct affairs in defiance of Delhi. That’s the unwritten epitaph scripted around the tombstones of both men.

The graveside of Mufti Mohammed Sayeed in Bijbehara’s Dara Shikoh Park. Sankarshan Thakur

The Sheikh became a willing party to accession in 1947 and crooned oneness with Jawaharlal Nehru on stage before thousands gathered in Srinagar’s

Lal Chowk:

Mun tu shudam

Tu mun shudi;

Man tan shudam

Tu jaan shudi;

Takas na goyad bod azeen

Mun deegaram

Tu deegaree

(I am You and You are me; I am your body, You are my soul; So none should hereafter say, I am someone and You someone else)

So singing out Amir Khusro’s sufi verse, Mohammed Sheikh Abdullah of the National Conference (NC) turned to embrace Jawaharlal Nehru, Kashmiri Musalmaan to Kashmiri Pandit. That was November 1947; the ink on Kashmir’s accession to India was only a week old. What followed would knock the stuffing off that sublime vow and render it a tattered feast for vultures.

The Sheikh went from accession to attempted secession and to forming a front to demand plebiscite, all within the following eight or so years. In 1953, Nehru had him arrested for leading what would later be called the Kashmir Conspiracy Case, and thrown into jail; Mirza Afzal Beg, a Sheikh confidant, cobbled together the Mahaz-e-Raishumari, or the Plebiscite Front; little came of it.

Omar Abdullah in Pahalgam on Wednesday. PTI picture

The Sheikh and Nehru patched up in 1963 and Nehru assigned the Sheikh to mediation with Pakistan, but upon Nehru’s death the following year, he was interned once again. It was only in 1975, after signing a pact with Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, that the Sheikh returned as chief minister of Jammu and Kashmir, a seat he held until his death in September 1982.

By this time, the original title of “Prime Minister” had been erased from the office of the state’s chief executive. Through the Nehru and Indira years, the Sheikh was repeatedly refused affirmation of Article 370 being a permanent feature of the Indian Constitution.

The Mufti often pitched his freshly minted Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) as a radical Kashmiri alternative to the NC.

But born into the Congress and trained in manoeuvring politics to the possibilities of power, he was able to tryst remarkably with Narendra Modi’s ultranationalist politics. He took many in his own fold by surprise when he agreed to form a coalition with the BJP in 2015, a “new deal” arrangement he justified in the name of giving representation to Jammu, which the BJP has swept.

The PDP helmsman passed away early the following year, bitter about how the coalition had fumbled and bumbled and probably dejected that his choice of ally was deeply disapproved by his south Kashmiri constituency. Daughter Mehbooba Mufti decided, after prolonged pondering, to press on with the unlikely partnership her father had struck. It came as no surprise to anyone that the tango tripped the daughter and landed her sore on the floor.

Mehbooba Mufti in Jammu on May 19. PTI picture

When the Mufti embraced the BJP in 2015 what warmth there was for him in Kashmir turned cold. That frost came to rest upon his final place on earth. The evil that men do lives after them; the good is oft interr’d with their bones: Shakespearean tragedy has a canny kinship with Kashmir, extant fact validating classic fiction.

The unfavourably inclined will say that the late Mufti Mohammad Sayeed spent his twilight sleeping with the enemy and was probably blessed he never had to get off bed to face the consequences. Mehbooba cannot hope to be half as fortunate.

Nor Omar Abdullah, grandson of the Sheikh, and de facto lead act of the NC, who too must contend with the division and diminution that came alongside the monumental announcements of August 5, 2019. He, like Mehbooba, can no longer hope to be chief minister of Jammu and Kashmir as it used to be.

For a brief period, the storm around them drove the two inheritors together — Omar and Mehbooba made common cause with other Kashmiri political groups, protesting the bundling of Article 370 as well as the bifurcation of the old state into two Union Territories.

But it’s back to rigid rivalry now, the NC and the PDP fighting separate battles or battling each other. Omar’s Baramulla challenge was put to vote on May 20; Mehbooba awaits her bout in Anantnag-Rajouri — with Omar’s nominee, Mian Altaf, spiritual leader of the Gujjars and Bakerwals, and her chief rival.

The two graves, you could say, are also at each other, looking upon the story of their progeny as it unfolds.

Anantnag-Rajouri votes on May 25