Liberation is the loftiest of feelings. Even when you have to etch its emblem in pain.

Mrunal Karthik does not appear to be wanting in agency. Yet, when it came to ending her emotionally abusive but otherwise non-existent marriage, her adequacy seemed inadequate; her spouse refused to allow her full custody of their little boy. “He works and lives abroad. Some time back, he forced us to vacate our rented home in Mumbai; he just didn’t want to spend on us any more. This abandonment hit my boy hard,” says Karthik, in bet-ween pauses. So she waited till her son turned 18, and then announced her decision to divorce. Soon after that conversation, she went and got herself inked. It was her first. “It’s in Arabic and means ‘Fear Nothing’,” says the soft-spoken Karthik, who now has three tattoos, each with its own story.

Tattoos have been around for as long as one can remember. In the olden times, sailors had the face of Jesus inked on their backs to deter masters from flogging them. Members of ethnic communities — the Rabaris of Rajasthan, Aos of Nagaland or Mojaves of the Colorado region in the US — sport intricate patterns as a mark of belonging.

For many, it’s more intimate than a signature of affiliation, or beautification.

The birds in flight on Basudha Datta’s wrist may look fashionable, but for the 50-year-old, it’s deeper than just ink on skin. “A couple of years ago I was grappling with a situation. It became so oppressive that I felt like I needed a tether to my release... The birds were a reminder that I would be able to fly,” says Datta, adding that the needle didn’t hurt at all.

Paromita Mitra Bhaumik, who is a Calcutta-based psychologist, explains the possible subconscious workings. “Suppose you are going through an intense situation such as the death of a close one, divorce or even a positive happening like a huge jump in your career. In other words, you have to make a transition from point A to B. It could be your decision to undergo that journey or you could be pushed to do it. The momentous nature of the event affects the person you are, and there is a change in internal perception — you do not look at yourself the same way you did earlier. When this happens, you want the world to look at you in the same manner. You try to show this by some external change such as a cosmetic surgery, a piercing or a new hairstyle.”

From being seen as signs of social deviance or rebelliousness, tattoos have come a long way tosignify self-determination or provide a sense of control over one’s body. Especially so for women who have travelled a certain numberof revolutions.

“More women over 60 are getting tattoos for the first time. Recently, I saw a photo of an 80-year-old doing so just because she’d always wanted to,” says Margot Mifflin, a professor of English at Lehman College, City University of New York, US, who also writes about women’s histories and the arts. In Bodies of Subversion: A Secret History of Women and Tattoo, she chronicles the history of both tattooed women and women tattoo artists. “Sometimes, this is purely celebratory but it can also be a way of asserting control over the body in face of uncontrollable events. Some women who’ve been abused get tattooed to reclaim their bodies,” she tells The Telegraph via email. “It’s also a kind of ritual confirmation of change that can be helpful in processing a transformative event, because getting a tattoo is so intimate.”

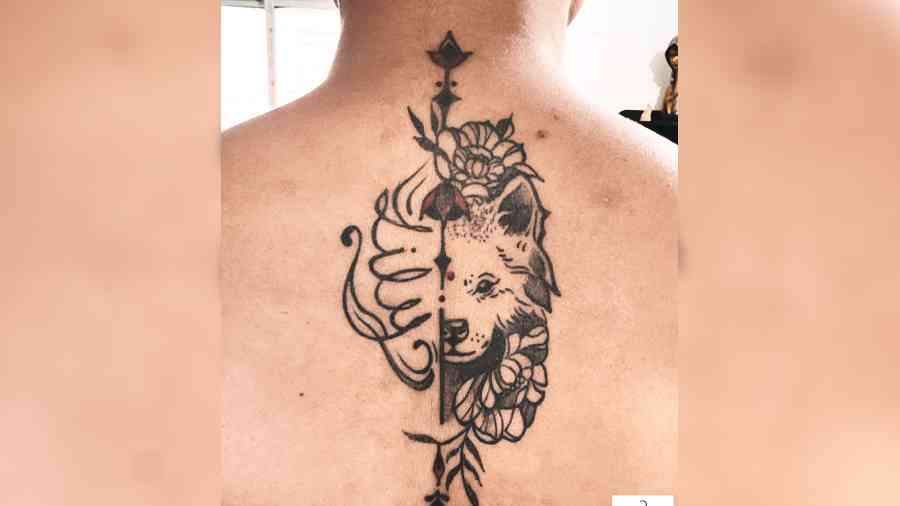

Calcutta tattoo artist Debanjali Das, 30, has much respect for mid-lifers who get inked. “They open up a lot of boundaries,” she feels, “because getting that indelible mark also means people are constantly judging you for it.” She tells the story of a woman who had arrived at her story — I wish to embrace the idea of being a woman, was her brief.

“We talked a lot and finally decided on a feather, an eagle feather to be precise, covering her whole arm. It signifies courage and at the same time says that you don’t have to be overly strong to overcome hurdles. You may be a little weak or soft and still make it.” Das’s client was very pleased with what she received. It wasn’t just a mark on her body, it became a part of her being.

“Many of my male clients idolise tattooed wrestlers and celebs such as Roman Wayne and Dwayne Johnson,” says Rajdeep Pal, an electrical engineer who has been drawing tattoos for 13 years. There are also portraits of a loved one, a parent or a child. Pal, an animal lover, sports his canine friend’s face on his arm. And adds, proudly, “In India, I’m the one who has done the most number of dog portraits.”

Das, on the other hand, notices a distinct love for Shiva among her male clients… an emblem of empowerment perhaps. “I have drawn a lot of Shiva figures and faces over the last two years,” she says.

One of Pal’s clients, a former substance abuser, reached point B, to use psychologist Bhaumik’s words, which included a fitness regime and professional success. “He wanted to write his recovery story,” says Pal. “It was the figure of a man walking up a flight of steps, at the end of which was a clock signifying his future.” He was very emotional about it, adds the artist.

Tattoo historian Mifflin finds men sporting this kind of tattoo too, “but not as often as women”.

In the meantime, Datta’s wild geese, high in the clean blue air, are heading home again.