Is there a secret to a good marriage? No idea. Does anyone know? It’s a happy accident... like the I-do moment between music and 1971. Frank Sinatra was moving into a semi-retirement mode and Elvis Presley’s comeback phase was slipping into ‘fried peanut butter and banana sandwich’ existence while the world was waking up to music of gladiatorial proportions. What’s Going On from Marvin Gaye, Blue from Joni Mitchell, Hunky Dory from David Bowie, Tapestry from Carole King, Teaser and the Firecat from Cat Stevens, L.A. Woman from The Doors, Just as I Am from Bill Withers, Aqualung from Jethro Tull, Every Picture Tells A Story from Rod Stewart and, of course, Untitled (Led Zeppelin IV). This wasn’t the era of pressed trousers and tea gowns; this was the time to experience a hailstorm of rock.

Fifty years later — when we are bang in the middle of an era when DJs are pressing buttons to see people respond — nothing is more relevant than 1971. Call me a grey-haired dinosaur with gut hanging out but I still like to revel in music that’s not uptight, songs that are liberating, poetry that’s set to music and musicians who believe that the world is big enough for everyone — a place where women could influence government and change domestic policies, a world where colour of the skin shouldn’t determine one’s fate and an age when new technology was not frowned upon.

Not that 1973 or 1975 was less perfect but 1971 was the year of transition, a time when singles gave way to albums that define classic rock. There’s nothing new there, for the David Hepworth book 1971 — Never a Dull Moment: Rock’s Golden Year (2016) has already said it all. It’s just that we are 50 years into the landmark year when award-winning director Asif Kapadia is seeking (and finding) answers with his Apple TV+ docuseries 1971: The Year That Music Changed Everything. And oh boy, we are still caught in the dilemma John Lennon expressed in his 1971 song — How? from the album Imagine: How can I go forward when I don’t know which way I’m facing?/ How can I go forward when I don’t know which way to turn?/ How can I go forward into something I’m not sure of?

Soundtrack of friendship and empowerment

TV broadcasting companies were fine-tuning ways to keep people locked up inside houses, watching what’s considered the first “reality” series, An American Family, with cameras following Bill and Pat Loud and their good-looking family to the point when their marriage was being pushed to breaking point. Not everyone was hypnotised, not the youth. Young women had heroes to look up to — Carole King and Joni Mitchell.

King’s Tapestry remains the soundtrack of friendship and empowerment. It came at a time when women were supposed to move from their father’s house to that of their husband’s by the time they were around 20 years old. Yes, the birth control pill was already approved but its use among unmarried women was unthinkable.

In a brilliant essay, Elizabeth Keenan had pointed out that King’s life reflected this reality. She met Gerry Goffin at Queens College and they soon married, becoming pregnant when she was 17. The two became in-demand songwriters, giving hits to artistes like Aretha Franklin, The Drifters and The Chiffons but their marriage was also falling apart. Her life and music merged on Tapestry, piercing through a male-dominated music industry.

Joni Mitchell prepares for a shoot for the fashion magazine Vogue in 1968. Picture: Jack Robinson

Clean, crisp vocals accompanied by the piano helped surface a deeper sense of truth, offering a close look at the private experiences of women. It was a moment when women finally found praise for writing music that reflected their lives. Tapestry is not just a soundtrack of a generation but a celebration of love, resilience and messages that could be passed from mothers to daughters.

Even in 2021, we can’t help but sing along (at least in our heads) with King: Winter, spring summer or fall,/ All you’ve got to do is call/ And I’ll be right there/ Ain’t it good to know, you’ve got a friend. Or share her frustration when she sings: So faraway/ Doesn’t anybody stay in one place anymore/ It would be so fine to see your face at my door/ Doesn’t help to know you’re just time away. And she sings it like she feels it, minus exaggeration in the heartbreaking It’s Too Late: But it’s too late, baby, now it’s too late/ Though we really did try to make it (we can’t make it)/ Somethin’ inside has died/ And I can’t hide and I just can’t fake it.

Women still long for a world where they can pour into the mould seen on the cover of Tapestry — enjoying a make-up-free life, at ease curled up near the window without having to worry about the judgemental world outside.

Also unwrapping a sense of intimacy is Joni Mitchell. Instead of excavating her discography for nuggets of her personal life, look at the way her music connects with the audience. On the 1971 album Blue, she becomes a friend and a teacher, a fellow sufferer and a painter with words. Each time River is played, it’s okay if misty eyes greet you: It’s coming on Christmas/ They’re cutting down trees/ They’re putting up reindeer/ And singing songs of joy and peace/ Oh I wish I had a river I could skate away on. She had described her emotional state while working on Blue to be “like a cellophane wrapper on a pack of cigarettes”. Decades later, British singer-songwriter Sam Smith while covering River confessed: “Joni Mitchell is one of the reasons why I write music.”

The 28 years of her life leading up to Blue, saw her survive polio, put her baby up for adoption and witnessed one of her greatest compositions — Both Sides Now — turning out to be a hit for someone else.

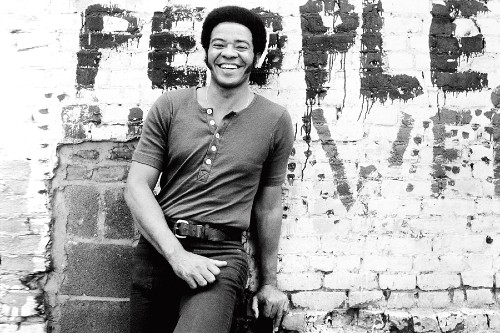

Bill Withers Sourced by the correspondent

Tumbling into USA

It was also the time two forces in the music industry were shaping up —Elton John and David Bowie. The nothing-is-impossible message of the two Englishmen was defining popular culture across the pond, in the US.

After leaving England in August 1970, events unfolded quickly for John — his self-titled second album arrived containing Your Song, America fell in love with him, so did the likes of Leon Russell, Bob Dylan and The Band, he lost his virginity to a man (John Reid, who later became his manager) and then in 1971 arrived the song Tiny Dancer on the album Madman Across the Water. The song captured the free-spiritedness of California in the early ’70s, of Los Angeles which, many believe, took over as the music capital from New York. The song captures a defining moment in pop culture, something that’s well documented in Cameron Crowe’s 2000 film Almost Famous.

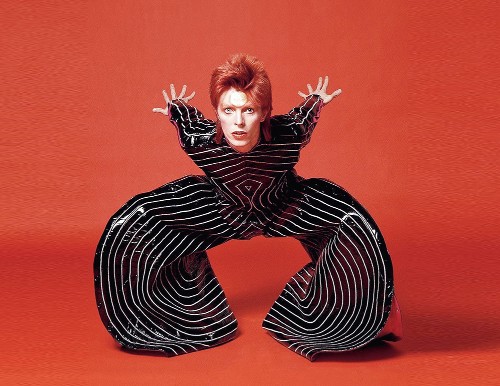

Also flying in from Britain was David Bowie in January 1971. “It really was a pudding. It was a pudding of new ideas. And we were terribly excited, and I think we took it on our shoulders that we were creating the 21st century in 1971. That was the idea,” said Bowie in a 2002 interview with NPR.

His first US visit was spent promoting the album The Man Who Sold The World and finding inspiration for his 1971 masterpiece, Hunky Dory. Identity-morphing Bowie hit the streets in America in a flowing velvet frock. “It’s a pretty dress,” the singer thought. But some people had an extreme reaction to offer: “Kiss my ass!” yelled a pedestrian while pulling a gun from his belt and waving at the man in a dress.

It was while travelling by bus from Washington D.C. to California, he penned some of the songs in the 1971 album — Andy Warhol, Song for Bob Dylan and the Lou Reed-inspired Queen Bitch. Later, he came up with the anthemic Changes, which was a way of saying, “Look, I’m going to be so fast, you’re not going to keep up with me”, and the song Life on Mars?. Of course, it paved the way for one of the greatest albums ever, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars.

Three other Brit voices were also being heard. John Lennon — already a star in America because of his Beatles tag — was at the start of his long fight to sought permission to remain in the country as a permanent resident.

The second was Marc Bolan, the mastermind of the English rock group T. Rex. Like Bowie, he portrayed an androgynous look that continues to influence people like Lenny Kravitz and Kate Moss. In 1971, his group gave the world Electric Warrior, a flamboyant album. “I am my own fantasy. I am the ‘Cosmic Dancer’ who dances his way out of the womb and into the tomb on Electric Warrior,” the singer had told Record Mirror.

And there’s Rod Stewart with his Every Picture Tells a Story, an album that rocks as hard as any from the era and is unabashedly personal, more so on the track, Maggie May. “I met an older woman who was something of a sexual predator. One thing led to the next, and we ended up nearby on a secluded patch of lawn. I was a virgin, and all I could think is, ‘This is it, Rod Stewart, you’d better put on a good performance here or else your reputation will be ruined all over North London.’ But it was all over in a few seconds,” he described the encounter in an interview with The Wall Street Journal. A few years later, he made the US his home for some decades.

David Bowie Sourced by the correspondent

A new Europe

Though a number of musicians moved to the US in the 1970s, Europe was witnessing pockets of youth revolution, fuelling a new era of music. Berlin was becoming the unlikely address for artistes and musicians from around the world. After decades of repression and scars of Nazism, the underground scene was suddenly thriving, at least in West Germany and the industrial new generation was discovering new sounds. Kraftwerk (“electric power plant” in German) was at the forefront, abandoning traditional rock instrumentation for what still was experimental synthesiser/electronic technology. In Britain, Pete Townshend was ensuring that the history of music remained inseparable from the history of technology. The synth-driven intro of The Who’s Baba O’Riley heralded a new chapter in music.

Meanwhile, the young in England were on a new journey when the Oz magazine trial brought musicians like John Lennon and Yoko Ono to the streets. The British edition of the magazine started in 1967, a darling of the underground press. By August 1971, it became the target of the longest obscenity trial in British history. At the heart of was the ‘School Kids’ issue of the publication. Three of its editors — Richard Neville, Jim Anderson and Felix Dennis — were charged (and arrested) for conspiring to corrupt the morals of the young. Ultimately released, but they gave birth to the dark Yoko-Lennon song Do The Oz.

At the same time, youngsters were tuning into another revolutionary musician while “Keep Britain White” graffiti was being painted — Bob Marley. It was music that educated the people to not remain silent. Hidden inside 1971’s Soul Revolution is Sun Is Shining, which is said to have come to Marley after listening to Eleanor Rigby. Also from the same album comes Fussing and Fighting. But the other 1971 track we can’t forget is the scorching Trenchtown Rock (non-album single).

Carole King Sourced by the correspondent

Sustained grit

The revolution was also continuing in the United States where people between gulps of Coca-Cola were made to think of a world that was fractious in the 1971 advertisement featuring the New Seekers turning in a bubbly version of I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing (In Perfect Harmony). On the one hand were Ike and Tina Turner, turning in outstanding interpretations of Proud Mary and I Want To Take You Higher while on the other were the Staple Singers, which evolved from a gospel group into a pop-protest group.

The Turners wanted to see the influence Black American music was having on newly independent nations like Ghana, a country the duo travelled to in 1971 with Wilson Pickett, Roberta Flack, Voices of East Harlem, the Staple Singers, Les McCann and Eddie Harris. The trip increased Tina’s confidence in herself and her music… enough confidence to walk out on Ike in 1975 after years of physical abuse at his hands.

While James Brown was living a rags-to-riches story, inspiring a new generation of musicians and taking his presence beyond the US with songs like Hot Pants and Make It Funky, Marvin Gaye was making a political statement with What’s Going On. The message in the track is timeless: Picket lines and picket signs/ Don’t punish me with brutality/ Talk to me/ So you can see.

And there was Bill Withers, who never wanted a few trumpets and three girls as backup singers. He was a working man when music came his way. Had he been forced to bow to pressures of music labels, Withers was more than happy to go back to his job of making toilets for 747s. What he has left behind is a treasure trove of music that spells timelessness, like Ain’t No Sunshine. Though record label executives stereotyped him and even suggested covering Elvis Presley’s In The Ghetto, Withers decided to walk on with his gritty lyrics.

Keeping them company was Isaac Hayes — Stax Records’ most prominent voice — who wrote Theme from Shaft, which ultimately won the best original song Oscar the following year, making him the first African-American composer to win the award. In 1972, Curtis Mayfield pushed the boundaries with the soundtrack of Super Fly.

No, 1971 is not the be-all and end-all of the best in rock but it certainly evoked a cross-cultural Venn diagram. My father is 70 and is only snob about afternoon siestas. As a 20-year-old he was incapable of restraining himself from applauding the timelessness of the music he was listening to then. Fifty years later, he continues to find that music relevant and subversive, hoping it gets passed down generations. Instead of making it a scholarly exercise like wine-drinking, 1971 remains the box Joni Mitchell spoke about in A Case of You: Oh, I am a lonely painter/ I live in a box of paints/ I’m frightened by the devil/ And I’m drawn to those ones that ain’t afraid. Dive in, for 1971 will always remain a refuge and a reward for those who care to fight for anything that matters.

Music to stream

Elton John: Madman Across The Water

Rod Stewart: Every Picture Tells A Story

Led Zeppelin: Led Zeppelin IV

Carole King: Tapestry

Joni Mitchell: Blue

David Bowie: Hunky Dory

Marvin Gaye: What’s Going On

John Lennon: Imagine

Bill Withers: Just as I Am

Jethro Tull: Aqualung

Fleetwood Mac: Future Games

Cat Stevens: Teaser and the Firecat

T. Rex: Electric Warrior

The Doors: L.A. Woman