On a March evening, when the Calcutta air is yet to turn surly with heat and sweat, a small crowd has gathered to listen to Mallika Sarabhai, dancer, choreo-

grapher and activist, at TRI, the new arts centre in south Calcutta. As I wait on the softly-lit terrace, with the breeze blowing in some more light from all around, I am happy for the cover of the night, and that I am so much above ground, which allows me to only see foliage and darkness, protecting me from the glare of billboards and flex and glow signs.

This is a brief respite for me from the normal; but for Mallika, the aesthetic is a choice, a defiant one. It is political. As she walks in to take her seat, I see how upright her bearing is, how she holds her head high and how strikingly beautiful she is.

At 71, Mallika is respected as much for her art that fuses the classical and the contemporary, as for speaking out against Right-wing politics. She speaks softly, but clearly, weighing each word, without mincing any. She is in Calcutta for her performance Past Forward, which features the nayika, the female protagonist of Indian classical dance, but in unexpected moods.

The TRI event is a Pickle Factory Dance Foundation initiative. Mallika is in conversation with Sumona Chakravarty, founder of Hamdasti, a Calcutta-based art platform, and vice-president at DAG; and Madeleine St. John, director of TRI.

Mallika speaks simply while res- ponding to the theme, “employing the feminine properties of mutability to shape spaces for movement(s) as we shape our bodies within them”. She believes the classical dance form is gender-neutral; it becomes gendered with the way it is performed.

She also talks about the home she grew up in, in Ahmedabad, from which her own practice and that of her mother, the pioneer dancer and choreographer Mrinalini Sarabhai, cannot be separated. Mrinalini helped to bring classical dance out of the temple, and women dancers out of disrepute.

Mallika refers to her mother’s composition, Memory Is a Ragged Fragment of Eternity, which was created after Mrinalini heard about young women’s deaths around her. “When Jawaharlal Nehru watched it, it led to the first white paper on dowry,” says Mallika.

Her father was Vikram Sara-bhai, considered the author of India’s space programme. The family home — she still lives there — was her mother’s dance school. “When I came back from school there was no place in the drawing room, because dance lessons were going on there, and there was no place in the dining room, because dance lessons were going on there,” she smiles.

At the Darpana Academy of Performing Arts, the idea was to use art for social change. “Never had Bharatanatyam been used with hatred or violence,” Mallika says, referring to the present.

Two days after the TRI event, she has been able to spare some time for an interview. We are in a hotel lobby, other phones buzz as we speak, but that does not seem to disturb her. In the morning light, I notice that the composure of her face can be touched with a sternness at times. I want to hear more about her childhood, and the life she chose.

She talks about Mrinalini again. “My entire aesthetic comes from her aesthetic,” says Mallika. “Her passion for the crafts. Her passion for things indigenous. Her passion for things that have texture and have a reality rooted in the soil. Today, I would wear hand-smelted silver rather than a diamond from Van Cleef,” she says, pointing at her silver earrings, two different sets in two ears.

She took up dance seriously when she was 22, Mallika says, after a period of depression. When Peter Brook’s The Mahabharata happened, she went on a world tour with the production. At this point she looks me square in the eyes. “This is a bit tedious,” she says. The particulars of her life are all over the Internet.

So I ask her about the aesthetic in the public sphere, in the body politic. “Plastic”, she says, is the word that describes the dominant imagery and iconography that we see around us. “Everything looks the same,” she says. This is the very opposite of the aesthetic that Mallika inherited from her mother. Everything is made the same way, ideas too, which turns them into products, easy to market, easy to sell.

And you’ve been...” She finishes the sentence for me: “...a staunch critic of the government.” It has not gone unnoticed. Her performances had been the main source of income for Darpana. Mallika would be invited to perform at about 60 shows every year. In 2014, after the BJP came to power, the invitations dropped to three. The situation has not improved much in the last 10 years. But she will not give up. She will fight the good fight. She has never left Ahmedabad. “We must never cede ground,” she says.

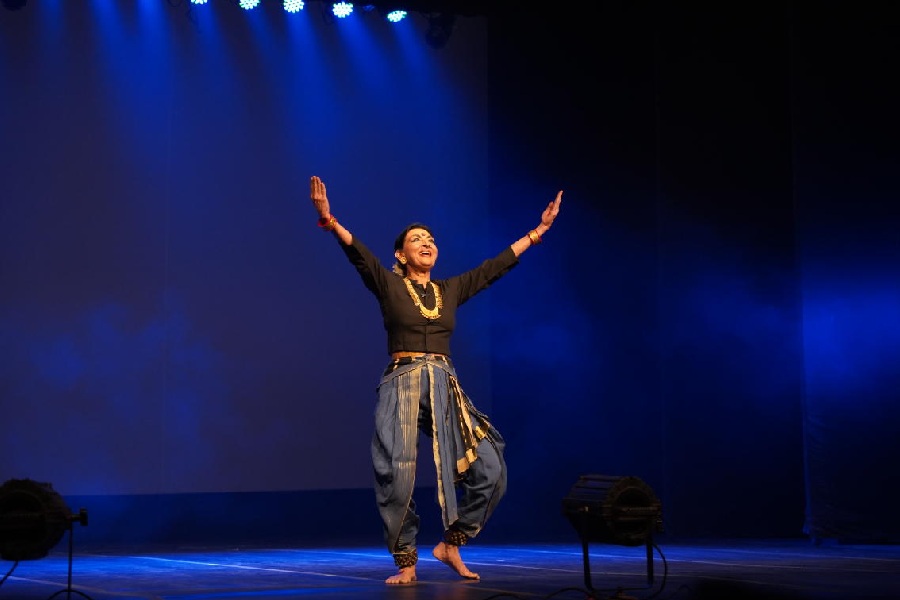

In the evening she dazzles at the performance, which explores a woman’s role within the classical dance form, and within social roles, even as it sets Bharatanatyam cheekily, in one item, to rap.

She ends the interview with a little story. At Darpana, a tree died. Its bran-ches were cut off and its trunk carved on. But now from the trunk of the dead tree, another plant is shooting up.