You might mistake it for a photograph, but it actually is a print of a painting from 1884. This work by Russian war artist Vasily Vasilyevich Vereshchagin shows sepoys in white tied to muzzles of cannons and uniformed British soldiers standing in attendance.

The painting titled Suppression of the Indian Revolt by the British in India was on display as part of a recently concluded exhibition at Gorky Sadan in Calcutta. The exhibition commemorated the momentous Indo-Soviet Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Cooperation of 1971.

In a room full of Indo-Russian literature and art, Suppression of the Indian Revolt stands out for its detailed and realistic depiction. It also represents the Russian stand on the British colonisation of India. “People of Russia feel proud of the fact that Russia was perhaps the only country in Europe where the ‘right’ of the British to possess and rule India was called into question, where the ‘good deeds’ of the colonies were disputed,” reads the long caption.

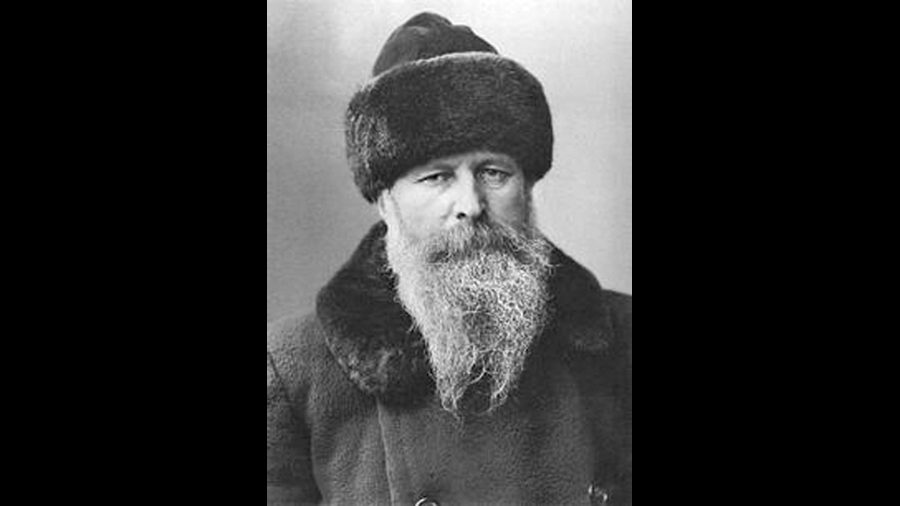

Vereshchagin had travelled to India twice, in 1874-1876 and again in 1882-1883, says Gautam Ghosh, who is the programme officer of Gorky Sadan. These travels were primarily to collect ethnographic material for his series of paintings. He almost froze to death in the Himalayas and fell ill with fever from the tropical heat, but he did more than 150 sketches during these trips. Most of them are now at the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow. The tall, stately soldier with a flowing beard seen in many of these canvases is Vereshchagin himself.

After graduating from military school in 1860, Vereshchagin entered the Imperial Academy to become a history painter. His outraged landowner father cut off all financial support. At the academy, he became a member of the Peredviznikhi or The Wanderers, a group of Russian painters who rejected restrictive classicism and embraced a more realistic, humane art for the common man.

At 26, Vereshchagin experienced war — he accompanied the Russian army under General Konstantin Kaufman on an expedition to modern-day Uzbekistan. When Hajji Nawab Kalb Ali Khan Bahadur declared war on the Russian Empire in 1868, the governor-general of Turkestan, Konstantin von Kaufman, needed a cartographer for the Russian army. Vereshchagin offered to join the forces as a volunteer. He was granted a junior officer rank and soon after he left for Samarkand.

Vasily Vasilyevich Vereshchagin Pictures, courtesy Wikipedia

Thereafter, he frequently travelled to areas of conflict not only to observe but also to play an active role, as he felt it was impossible to depict the reality of war without taking part in it personally. “It would be impossible,” Vereshchagin wrote, “to achieve the aim I have set myself, to give society a picture of war as it really is, by observing battles through binoculars from a comfortable distance. I have to feel and go through it all myself. I have to participate in the attacks, storms, victories and defeats, experience the cold, disease and wounds. I must not be afraid to sacrifice my flesh and my blood, otherwise my pictures will mean nothing.”

Vereshchagin’s realistic battle scenes soon put him on the warpath with military establishments. Field Marshal Helmuth Moltke forbade German soldiers to see The Apotheosis of War. He felt it would confuse them. The Austrian war minister imposed restrictions on Vereshchagin’s 1881 Vienna exhibition. Russia also placed a ban on Vereshchagin’s exhibitions as well as a ban on reproductions in books and periodicals. For 30 years the tsarist government did not acquire a single painting of his.

In this early work, Vereshchagin focused most of his efforts on depicting the brutal business of war: from countless paintings of the dead or dying to barbarians holding up the severed heads of various imperial officers. In his painting They Celebrate (1872), Vereshchagin shows a crowd celebrating a long line of decapitated human heads on the tops of tall wooden poles.

When Vereshchagin’s work was finally exhibited in the West, many people were shocked. Even his friend General Kaufman accused him of falsifying history. Says Francis Asquith of Sotheby’s and a specialist in Russian art, “What was unusual about Vereshchagin and what struck the public and critics during his day was that he did not try to glamourise war. He was the first genuine war reporter who painted war as it was.”

But it was not just the atrocities of war that caught his eye. His Taj Mahal (1876) depicts a time when the Yamuna river was clean and clear. Vereshchagin painted several portraits of Indians. He was in love with the Himalayas and the Tibetan plateau.

Writes historian Irina Chelysheva, “His works are all so saturated with the special atmosphere of India, are so filled with its rich world of colour, the blinding colours of the midday sun, that they involuntarily give rise to an ethereal feeling of being present in the country.”

Vereshchagin also painted The State Procession of the Prince of Wales into Jaipur (1876), which is supposed to be the third largest painting in the world. It features an important moment in Prince Albert-Edward’s tour of the Indian subcontinent. The painting was originally the property of one Edward Malley of New Haven, US. It was later acquired by Maharaja Madho Singh II of Jaipur and subsequently gifted to Calcutta’s Victoria Memorial Hall in 1905. “Curzon had asked all the princely states to donate to the collection of Victoria Memorial. In fact, he had arm-twisted many of the princes in doing so,” says Victoria Memorial Hall curator Jayanta Sengupta, but that is another story.

The painting has recently been restored and now occupies a pride of place at the Royal Gallery of Victoria Memorial.