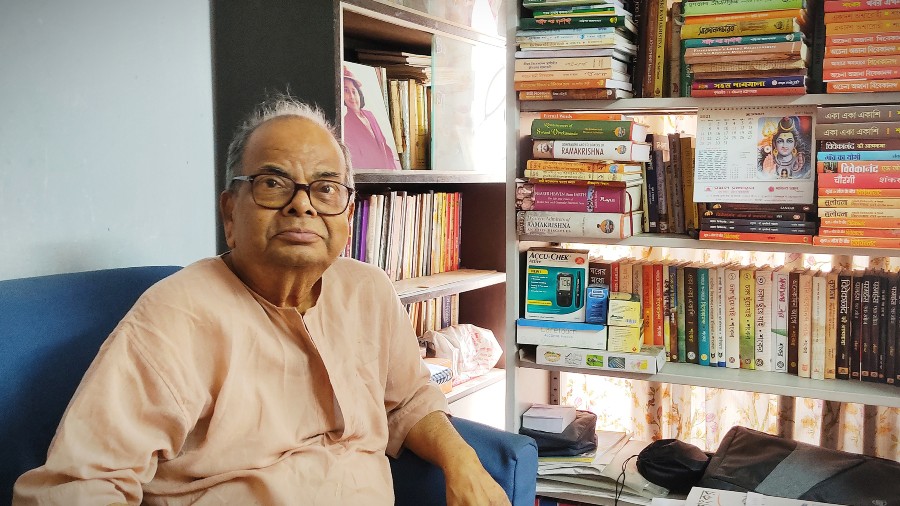

The modest living room of the south Calcutta apartment is walled with books. Vivekananda’s life and works, Ramakrishna’s Charanamrita, Amartya Sen’s The Argumentative Indian. The 88-year-old Mani Sankar Mukherjee — popularly known as Sankar — has just been conferred the Sahitya Akademi Award. He says, “I have been told by many that I should have got it earlier. But I want to ask them, are literary awards like pieces of dowry that must be given to all writers?” Is he then tempted to turn it down, do award wapsi, in protest against the times? Sankar deadpans, “That was started by Rabindranath Tagore when he returned his knighthood during the British rule. We have just a few titles or so. It’s difficult to get them and it’s equally difficult to give them up.”

A conversation with Sankar is telescopic, as I discover. The narrative opens out backward or forward delightfully at his whim. I simply enjoy the different views.

Sankar was born in Bongaon in North 24-Parganas, then known as Jessore district, where Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay of Aam Aantir Bhenpu and Chander Pahar too lived. “He lived a humble life of a schoolmaster,” says Sankar. He himself, however, had to leave Bongaon for Calcutta when he was four or five. “The Bongaon court’s jurisdiction got divided and the legal practice of my father suffered. So he decided to shift.”

The family settled down in Howrah, Calcutta’s twin city on the west bank of the Hooghly. The family started living in Bihari Chakrabarti Lane or what is known as Chowdhurypara. From the bucolic suburbia of Bongaon, the four-year-old now had to negotiate the narrow lanes of the city. Says Sankar, “Howrah was not my birthplace but it is my motherland.”

Sankar’s father Haripada had been a great admirer of Girish Ghosh, the man who is hailed as the father of Bengali theatre; he started his life as a dramatist. Some of his works were staged at Star Theatre, then known as Kohinoor. But then came a time when Haripada decided that it was futile to pursue this line of work. He taught at Hindu School for a while and then turned to the practice of law. In all of this, he lost a few years, which is why he did not want his children to pursue a literary career.

The Mukherjees struck root in Howrah; Sankar’s father became immersed in work, his mother got busy minding the younger children — Sankar was the second of 11 brothers and sisters. And that is when Sankar became friends with Badalkaku.

Badalkaku, a bachelor, lived next door to the Mukherjees, with his mother and brother. “He didn’t marry because then he wouldn’t have been able to pay for his brother’s education,” says Sankar.

The free flowing and apparently random reminiscings weave themselves into a pattern. Sankar continues.

There were three pictures in Badalkaku’s room — one of Napoleon, the other of Mahatma Gandhi and one of Mr Livingstone, his boss. Badalkaku was a stenographer and was very thorough with his work. He read The Statesman regularly with an Oxford English Dictionary by his side. “Badalkaku couldn’t make up his mind. He said, ‘I love Napoleon, but I can’t leave my motherland, so I love Gandhi too and I like my British boss, Mr Livingstone too’,” says Sankar with a fond laugh.

But why did Badalkaku love Mr Livingstone so much? “He would say, ‘I think those who don’t support Mohun Bagan cannot be good people. So I had asked whom he (Mr Livingstone) supported. He said he supported Calcutta Football Club, a small first division club, which invariably lost in the first round of the IFA Shield match. I asked him why he supported such a club and Mr Livingstone said after Calcutta Football Club loses, he secretly starts supporting Mohun Bagan’.” I understand that these stories shaped the young Sankar’s mind.

Badalkaku took Sankar in a horse-drawn carriage to watch a Mohun Bagan match. Sankar tells me, “He took me to Dalhousie, to his office. Mr Livingstone was off for lunch, so he made me sit in Mr Livingstone’s chair and said, ‘I can’t sit there but maybe you will, one day’.”

Once, when Sankar had to deliver a speech in school on what he would do in future, it is Badalkaku whom Sankar sought out for help. The essay read: “I bathe in the Ganga first thing in the morning. One day, I heard a fellow bather remark — ‘Nothing will happen to this pen-pushing community’. I don’t want to become a king, I want to be a writer, I want to belong to this pen-pushing community.”

The headmaster was very pleased with Sankar’s speech.

In 1947, some months before Independence, Sankar lost his father. “There were seven brothers to feed and nothing but a few insurance policies. My mother told me I had to stop studying and start earning. The landlord took pity on us and lowered the rent,” he recalls.

The Mukherjees’ rented place had electricity, but one day they received a bill of Rs 82 as against the normal bill of Rs 3. When they couldn’t pay, a man from the electric supply office, dressed in shirt and shorts with a hat on his head, came over and cut the line. It was around then, in the light of hurricane, that Sankar wrote his first novel, Koto Ajanare or All The Unknown.

During his infancy, Sankar’s mother had his horoscope cast for him. It predicted that the newborn would transcend several professions. And so, Sankar went from being babu to shaheb barrister to literary chronicler of high court para to sheriff of Calcutta...

But his ample journeying notwithstanding, Sankar returns to memories of Howrah time and again. He says, “It has given me everything, it has given me Badalkaku, Vivekananda school, mastermoshai of Vivekananda school who gave me a temporary job when I needed it most, Bibhutida who taught me stenography and introduced me to Barwell sahib (a barrister at Calcutta High Court), Sankari Prasad Basu (known for his scholarship on Vivekananda) who encouraged me to write and in whose footsteps I followed and finally wrote Achena Ajana Vivekananda, and also Asit Krishna Bandopadhyay, who was my neighbour and who has taught me so much...”

While he made a name for himself in fiction, Sankar also dabbled in other forms of writing, namely biography. When asked why he made this transition, Sankar says, “What is the difference between fiction and biography? In fiction, many of the characters are actually based on real people. Badalkaku appears in my novels under a different name.”

Sankar has also infused his writings with his other loves. One such is his love for sweets. His book Rasabati is a work in the sociology of Bengali food. Rasabati being the creative term ancient kings of India used to refer to the kitchen. Sankar tells me, “I cannot cook, I cannot make a cup of tea, I haven’t been to a big restaurant. But I have an interest in food. Early on in life I didn’t have money to indulge my palate, and when I finally had the money I was, by the time, a patient of diabetes and hypertension.”

He continues, “Do you know, the first book Vivekananda bought was not the Bhagavad Gita but a book on French cuisine? The first institution he built was not the Ramakrishna Mission but a cooking club. Spiritualism came later in life for him. But he cooked wherever he went and introduced Indian cuisine to the West.”

According to Sankar, English translations of his works have given him a new lease of recognition. “Beyond Asansol nobody knew me. One day, a very popular Indian writer who was an adviser to a publishing house told them — ‘There is someone called Sankar. You should translate him.’ That was Khushwant Singh,” he says. Later Vikram Seth too recommended that Sankar’s Chowringhee be translated into English; he had read the Hindi translation gifted to him by his mother. Sankar met Seth at the London Book Fair in 2009. He says, “I had managed to go as far as Asansol. Khushwant Singh and Vikram Seth took me to London via Delhi. I have done nothing.”

Sankar tells me that his mother would say that more than Bengalis, the Hindi-speaking people loved his works. A reader from Uttar Pradesh had sent a packet of revadis (sweets) after reading him in Hindi. “Bengali readers only write letters and criticise. But a man from UP has sent you sweets,” she had said. Someone from Benaras had sent a packet of mangoes by train. It had to be collected from Howrah station, but when Sankar went to do as much, he found stones inside the packet.

As I prepare to wind up the mid-morning interview, Sankar says famously, “My biggest test is yet to come. I have to live after I die. You see, Bengali writers start living only after they die. You can ask anyone on College Street. The top 10 Bengali authors are all dead people. Let’s see if I can do that.”

Têtevitae

1933: Sankar is born in Bongaon, in North 24-Parganas district, then known as Jessore district

The family moves to Howrah soon after. He attends Howrah Zilla School and then Howrah Vivekananda Institution

1947: Passes the matriculation examinations and joins Calcutta’s Surendranath College, then known as Ripon College. Cannot complete his graduation due to financial constraints and starts life as a professional

1954: Writes Kata Ajanare and Chowringhee is published in 1962. There is an unfinished film by Ritwik Ghatak based on the first; the second is made into a cult film in 1968 starring Uttam Kumar and Supriya Debi. Soon after, his Nibedita Research Laboratory is published. His novels Seemabaddha and Jana Aranya are adapted by Satyajit Ray and made into films in 1971 and 1976, respectively Sri Sri Ramkrishna Rahashyamrita and Achena Ajana Vivekananda are two of his popular biographical writings

2021: Is awarded the Sahitya Akademi for Eka Eka Ekashi