A day after Prime Minister Narendra Modi made a signature spectacle of opening the refurbished Kashi Vishwanath Temple corridor, Samajwadi Party chief Akhilesh Yadav was in neighbouring Jaunpur district for a show of strength. If Modi was foregrounding his hard saffron Hindutva from Varanasi, Akhilesh appeared to present a counter, by courting a rainbow coalition of social sections. “Look around and see, how many colours of flags are with us,” Akhilesh said at the rally, waving at the crowd of supporters. “With all these colours we have formed a multicoloured alliance,” he exclaimed, and predicted that the defeat of the “monochromatic” BJP was certain.

The multicoloured flags represented some half-a-dozen regional and sub-regional political outfits Akhilesh’s red-and-green party flag has aligned with in its bid to oust the BJP from the country’s largest and politically most crucial state, Uttar Pradesh. These outfits claim the loyalty of splintered backward and extremely backward castes, many of whom had powered the BJP’s stunning victory in the last Assembly polls.

Can Akhilesh hope to defeat the mighty BJP with an army that on the face of it looks a rag-tag one?

Since his Jaunpur show in mid-December, Akhilesh’s drive has acquired greater heft, leaving the BJP palpably rattled. Two key backward caste ministers and several MLAs have quit the BJP and joined the Akhilesh camp, igniting fears of a Mandal-like OBC-backlash among BJP poll managers.

The ministers and MLAs who quit accused chief minister Yogi Adityanath, an upper caste Thakur, of neglecting the interests of backwards, Dalits, farmers and the youth.

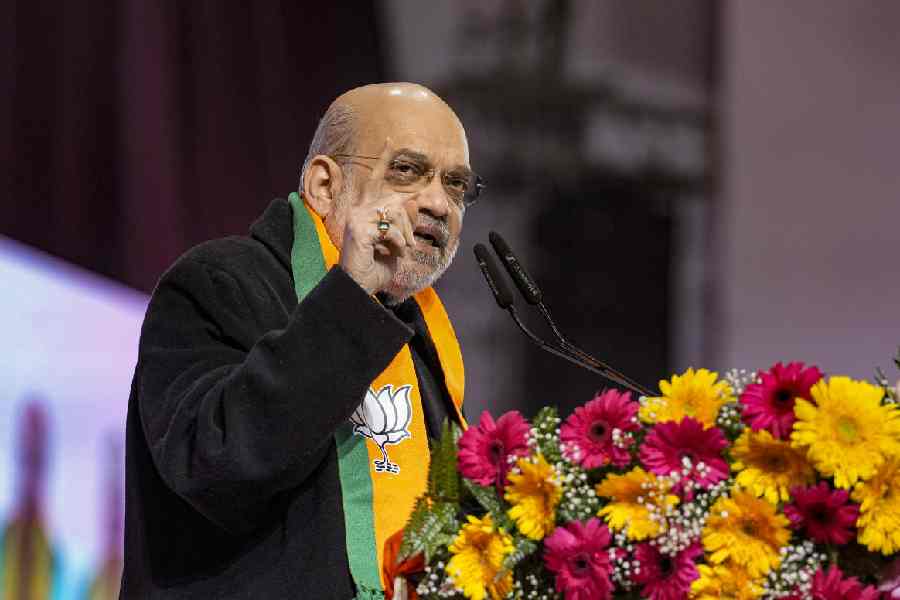

This sudden exodus pushed the BJP bosses into damage-control mode. Modi’s most trusted lieutenant, Amit Shah, stepped in and held late night parleys to secure electoral tie-ups with two OBC allies, Apna Dal and Nishad Party. A noticeable change was seen in the BJP’s poll strategy. The overemphasis on Hindutva was toned down and “garib kalyan” became the foregrounded slogan. A lion’s share of tickets so far has been given to OBC and Dalit candidates.

File picture of Yogi Adityanath Attribution: Chayan Majumdar

Akhilesh’s alliances with smaller parties are directed towards repairing what was undone during his maiden stint in power in 2012-17. The political and social dominance of the Yadavs in the wider OBC block had driven large sections of other backward castes into the BJP fold. By displaying the flags and leaders of most backward castes around him, Akhilesh is sending out a message that this time he is willing to share the power pie.

His slogan is “Naya Sapa” or a “New SP”. Slogans of “pichhdon ka inquilab hoga” (revolution of backwards will happen) are being raised in his rallies. He is even wooing Mayawati’s Dalit votaries by saying “Ambedkarites” should join hands with “Samajwadis” to save Baba Saheb’s Constitution from the BJP.

While questions remain on whether non-Yadav OBCs and Dalits will buy the “New SP” and ally with Akhilesh, chief minister Adityanath too needs to get his caste equations right. He is being widely accused of unleashing “Thakurvaad”, or the hegemony of Rajputs. “Yogiji ke raj mein Thakurvaad to hai,” many BJP leaders privately admit. The alleged dominance of Thakurs is believed to have upset not only the lower castes but also UP’s 12 per cent Brahmins, considered staunch BJP supporters.

The Thakur-Brahmin fault line in UP isn’t new, but Adityanath seems to have reopened scars with his brash Thakur espousal. Acknowledgement of Brahmin anger came from the top BJP leadership when it constituted a committee of Brahmin MPs and leaders to “remove apprehensions”.

Akhilesh would be naive to believe large sections of Brahmins would gravitate towards the SP merely because they are annoyed with the BJP. He needs a stronger voter base of his own. If Akhilesh’s “multicoloured alliance” is for eastern and some central regions of the state, in the west he has tied up with young Jayant Chaudhary-led RLD, which draws strength from the dominant Jat community. The SP is banking on the Muslim-Jat combination which the RLD will possibly rally behind the alliance. Muslims and Jats had parted after the 2013 Muzaffarnagar communal riots, but the long farmers’ agitation has brought the two communities together again.

Apart from the caste-centric alliances, Akhilesh’s big hope lies in the fairly wide spread anti-incumbency against the Adityanath government, driven by double digit inflation, joblessness, farmer unrest and the deep wounds of killer mismanagement during the second Covid-19 wave.

So far Akhilesh has moved well, given that his challenge is daunting. He has pushed aside the BSP and the Congress and established himself as the principal adversary, making the UP contest almost bipolar.

Defeating the BJP in UP may not be impossible, but it certainly is no easy task. It had secured nearly 40 per cent of the vote (312 seats) in 2017 and even the combined strength of the SP-BSP in 2019 Lok Sabha polls couldn’t stop the BJP and allies from securing nearly 50 per cent of the polled votes.

Akhilesh had seized power in Lucknow in 2012 with a little less than 30 per cent (224 seats) vote share; the BJP then had just 15 per cent and Mayawati’s BSP 26 per cent.

So Akhilesh needs a push of the kind the BJP managed between 2012 and 2017. “Multicoloured” alliances alone can’t achieve that. Besides, the Modi-led BJP is no more the “Brahmin-Baniya” party of the past. Armed with a cocktail of Hindutva, ultra-nationalism and welfarism — like cash doles for farmers and free food grains for poor during Covid-19 — the party has made deep inroads among backwards and Dalits.

It remains moot to what degree public anger against Adityanath will play on the vote. And apart from denting the BJP’s non-Yadav OBC block and rattling its upper caste base, Akhilesh would need to slice away portions of the BSP and the Congress’ loyal backers as well. Many pollsters believe that he can defeat the BJP if his alliance crosses the 35 per cent vote share.

“Why can’t we do it?” Akhilesh said in a recent TV interview on being asked how he could hope to defeat the BJP with barely 50 MLAs. “When I was in power, the BJP too had just 47 MLAs. If they (BJP) can get 325 seats, why can’t the SP and its allies touch 400?” he countered. Akhilesh exudes confidence that “unemployment, price rise and the damage due to Covid” would help him garner votes of all sections of society.

“After Mamata Didi, Akhilesh Bhaiyya will inflict a shock defeat on the BJP,” claimed an SP leader manning the party’s war room in Lucknow; he seemed assured that anger against the government is simmering across sections.

But there is at least one key difference between Bengal and UP: Mamata was the incumbent and defending her fortress, Akhilesh is the challenger at the gates of a fortress minded over by Modi himself. If Akhilesh is able to make a breach, he would not merely be taking UP, he would likely be altering the course of heartland politics.