He moves around in a three-wheeler, has a nine-year-old dog called Khalu, works out of a foldable office from the verandah of his mother’s house and is known to build homes for orphans and the ailing, the common man in cities and in villages. Architect C. Anjalendran from Sri Lanka thinks the current crisis his country is faced with will only make him and his countrymen more creative. He tells The Telegraph in a telephone interview from Colombo, “We are facing power cuts, there is no gas in the country since April, the government has been brought down and it’s easy to sit around and cry. But that is not what we are doing. We faced a similar situation in the early 1960s, when Sirimavo Bandaranayike’s government stopped imports, stopped people from going abroad. I strongly believe you get more creative because of such restrictions. In those days you queued up for bread, today we are queueing up for gas. Only, the notion of what is essential has changed.”

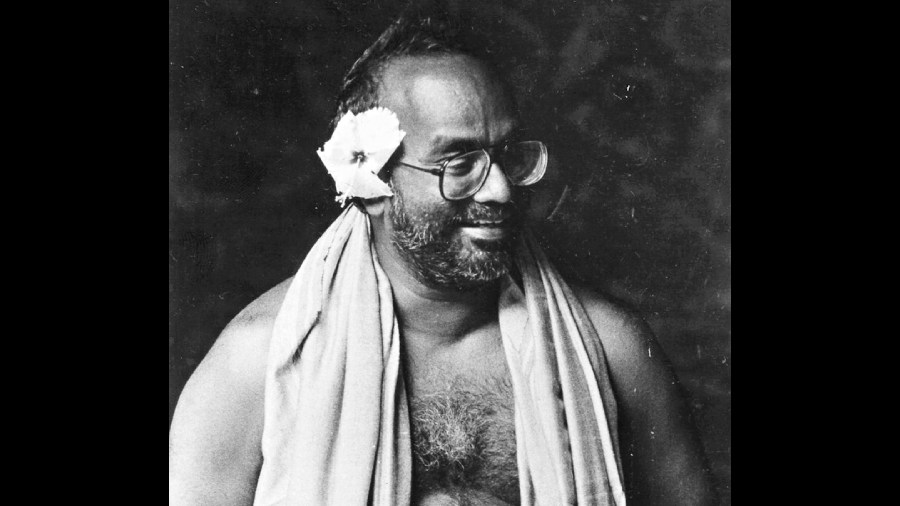

The architect, who was in Calcutta to deliver the fifth edition of the Charles Correa Memorial Lecture presented by Gujarat Ambuja, was apprentice to the grand master of Sri Lankan contemporary architecture, Geoffrey Bawa, for 10 years. He learnt by watching the master resolve the dilemmas of modern life and architecture.

He says, “Bawa was a non-talkative person, he never wanted to make major statements about architecture. In his whole life, he has probably made a general two-page statement and given one interview. He practised a kind of receding architecture, one that didn’t jump in your face.” He adds, “For Bawa, architecture should be quiet, a tranquil space, a space where you should be able to meditate.”

Anjalendran’s designs are deeply rooted in Sri Lankan soil and culture. He began his Calcutta talk by showing photographs of ancient pilgrim rest houses that are found in abundance throughout the country. Called ambalama, these are typically built on rocks to prevent damp and termite and overlook a stunning landscape.

“In Sri Lanka, we have a tradition where buildings are an integral part of nature. This pilgrim rest pavilion exemplifies that. You can put a sari or a sarong around its columns and you have privacy, and you can cook in the middle, it’s on the way to a pilgrimage,” he explained.

Showing another picture of a rest house in the middle of a lush green field, he said: “You can’t imagine this rest house without the landscape and the landscape becomes perfect because of the rest house. This is a tradition here and that tradition continues to Bawa’s garden called Lunuganga, where I lived for 10 years.”

Anjalendran’s slides on Kaludiya Kokuna, or the black water pond, an ancient monastery that gets its name from the dark reflections of the surrounding boulders in the water, showed how manmade rocks blended perfectly with the natural rocks of the landscape, boulders used as a retaining wall with third century Brahmi inscriptions and cave temples with representational streams. The last is an arrangement of pebbles which mimics a flowing stream.

“The Sinhalese have this amazing representational attitude. Though everyone thinks it is only the Greeks who understood visual illusion, the Sinhalese absolutely had it at around the same time,” said Anjalendran.

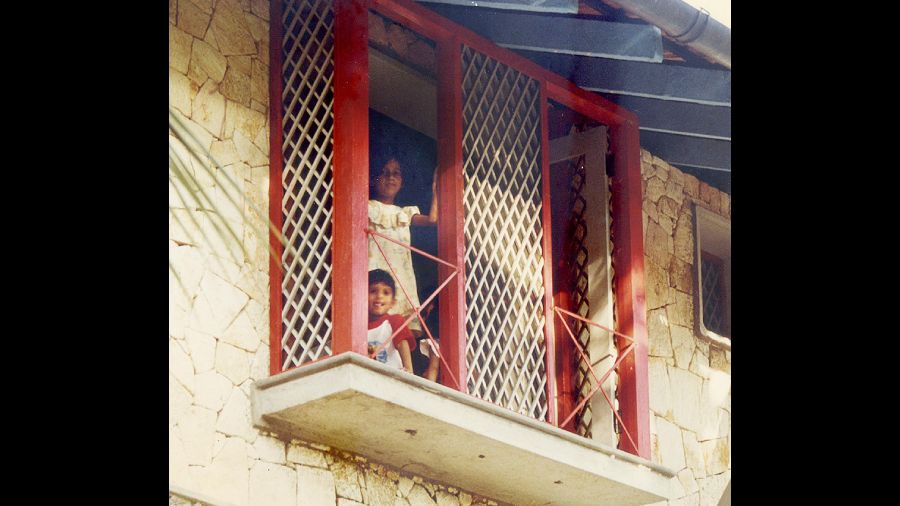

An SOS Children’s Village in Galle built by C. Anjalendran

He talked about the SOS village in Galle, a coastal town in southern Sri Lanka, which he designed. SOS Kinderdorf International is an NGO providing care for orphan and destitute children. Anjalendran said, “The village had rocks, the buildings were integrated into the rocks, and there was a frangipani tree there that linked all the buildings around it. Since it’s for children, we used colours. We salvaged old doors and windows that give the houses character and it’s cheaper, probably half the price of new ones. The difference between a good building and a bad building is that a good building, a happy building, is one where you spend more time building.”

SOS also asked him to build farm buildings for youth on two conditions: “That I wouldn’t charge a fee and the buildings would be built by the youth themselves.” They were built at a minimal cost.

“First, I built a cattle shed. A magnificent tree ties the whole project together, a cattle shed done for Rs 10,000 which equals INR 2,500. I gave the cow a window to have a view, to make it exciting, there is also a colourful door to it painted by the youth. These are things you do to make exciting houses with INR 2,500. I also built a piggery and henhouse, and put a weather vane to make it exciting. The director of the project was a friend of mine. He made the youth use earth, chemi-fix to bond and salt which is antifungal, and used six earth tones to paint the building,” said Anjalendran.

Words such as “tranquillity”, “peace”, “serenity” and “nature” pepper Anjalendran’s talk; a man whose country has been ravaged by decades of ethnic conflict and is, as we speak, imploding with economic and political crisis. The weary voice over the telephone tells me, “Perhaps all the more reason to seek tranquillity and peace, I think.”