Dressed to the hilt in Bajrangbali costume and wielding his gada, Nibash Sarkar was a spectacular presence at the BJP’s 2019 Lok Sabha campaigns in Bengal, including the Amit Shah roadshow in Calcutta that led to the destruction of a bust of Vidyasagar.

A few months later Sarkar passed away. He had reportedly killed himself, driven by the fear of the implications of the National Register for Citizens (NRC).

The documentary film A Bid for Bengal, made by Dwaipayan Banerjee and Kasturi Basu, visits Hanskhali in Nadia where Sarkar lived. Like him, everyone in his community there had migrated from East Pakistan (or Bangladesh, depending on the time). All of them had turned BJP supporters since Narendra Modi became Prime Minister in 2014. All of them now dread that the NRC, the BJP’s scheme to weed out “infiltrators” from Indian soil, will make them stateless.

Sarkar’s death illustrates the irony of the life of a Hindu like him. But his images in costume survive, emblematic of the new religious-political identity being imposed on Bengal. He embodied this change, literally, dressed as Bajrangbali, the strong new god in the Bengali Hindu firmament, the articulator of “Jai Shri Ram”, chant or threat depending on who you are.

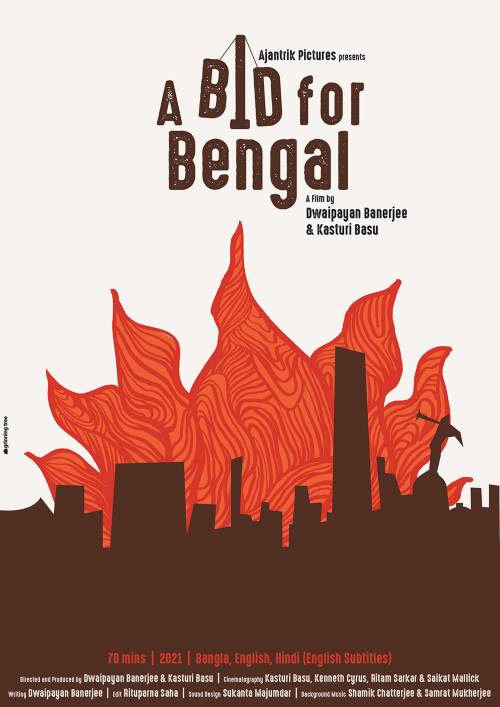

The film’s poster Courtesy Dwaipayan Banerjee and Kasturi Basu

This change, say the filmmakers who are partners in life as well, is the result of a well-organised, long-term programme on Bengal. The BJP may have lost the Bengal elections, but the Sangh Parivar was, and is, at work to make Bengal a part of its effort to build a Hindu rashtra. “Conversations have changed,” says Kasturi. “Some years ago, people would not have been discussing ‘Hindus and Muslims’ in a bus. Our film explores the ordinariness of the fascist project,” she says.

The ordinariness ensures invisibility: Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP) programmes hardly find mention in mainstream discourse.

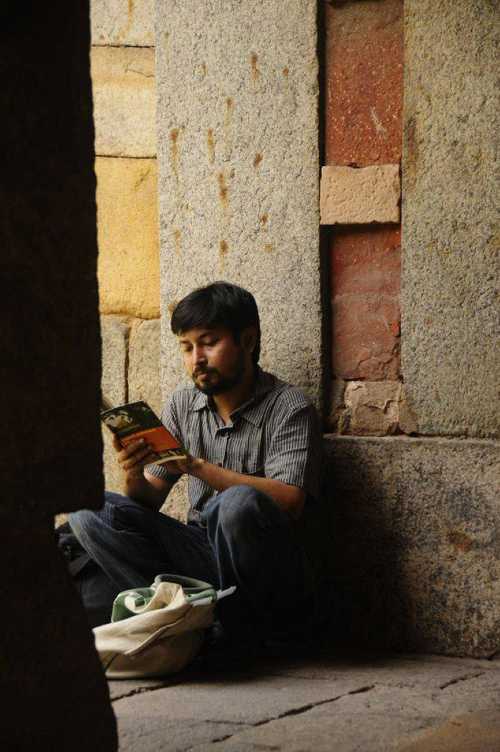

Dwaipayan Banerjee Courtesy Dwaipayan Banerjee and Kasturi Basu

In the film, an impassioned Sachindra Nath Sinha, general secretary of the VHP, eastern region, whom Dwaipayan and Kasturi met in 2019, talks about the organisation’s “success” in Bengal. It has penetrated rural Bengal and border and coastal areas, where national security is at stake, he claims. He rattles off statistics — VHP committees work in about 1,500 places in south Bengal and the VHP runs 250 formal and 2,000 informal schools across the state. At last count, Ram Navami was celebrated at 750 places in Bengal and 22 lakh people joined in the celebrations, chanting “Jai Shri Ram”.

The slogan is the key. Another scene shows a Bajrang Dal training camp held at Jalaberia in South 24-Parganas, where young men are somersaulting aggressively and serially to the chant of “Jai Shri Ram”, which would have been just bizarre if it was not so menacing.

But the most bizarre incident, perhaps, involves a cow census. In a scene shot by another filmmaker, Dilip Bhutra, secretary, cow development cell, BJP, West Bengal — yes, Bengal has one too — meditatively counts the cows on a farm as a woman mentions “Bengali cows”. These are presumably different from “Bihari cows”.

Kasturi Basu

Dwaipayan and Kasturi are among the founder-members of the People’s Film Collective, a platform that screens documentary films and political cinema for audiences in Bengal. Kasturi has co-directed a documentary on Communist leader and poet Saroj Dutta with another filmmaker; Dwaipayan was the associate director and screenwriter. Both were among the body of convenors of the citizens’ platform that coined and popularised the slogan “No Vote to BJP”, which became synonymous with the campaign.

The year 2020 changed the couple’s work as filmmakers. The threat of the BJP coming to power made them discard their “fly on the wall” roles, as they were making A Bid for Bengal, and their presence became more visible within the frames of their own film.

“I could not but heave a sigh of relief. But it was just that,” says Dwaipayan towards the end of the film, when the Assembly election results are out. It comes with a caveat. “With the complete decimation of the Congress and the Left Front, Bengal politics would never be the same again.” And the BJP has not done too badly. It won 77 seats to the Trinamul’s 213, but captured 38 per cent of the vote share against the Trinamul’s 48 per cent.

“In Bengal, there is a common consciousness, a history of togetherness,” says Kasturi. But this history has not been pristine. There has been a long chronology of riots in Bengal and the fault lines remain, perfect places to grow the idea of a Hindu nation.

The idea is nourished by memory and memory is not always a true thing. It can be partial, it can be deceptive. “Memory can be made,” says Kasturi. Memory can make pure victims of one community, pure perpetrators of the other.

This is the other Hindutva project; which WhatsApp University works on.

Our Prime Minister can, too. On Independence Day this year, when India turned 75, he marked the event as Partition Horrors Remembrance Day, quite forgetting that the horrors were felt not on this side alone.