Once upon a time there was an urban legend about a kalo pori guarding our skies. Kalo is the Bengali word for black and pori means fairy. And that is how the finial atop the central dome of Calcutta’s Victoria Memorial fluttered its way into my imagination all those years ago. Fantastic and female.

I had no idea who created it and why, and I dare say I was most likely not in the minority. Truth is, in post-Independence India, the colonial context of the memorial had gotten blurred. For long years, before it turned platform to lit fests, talks and a much-talked about political soiree, the memorial’s overwhelming identity was that it was a safe haven for the city’s lovers.

As for the kalo pori, it is difficult to say what one and all made of it. What is certain is that the interest in this exotic weathervane and lightning conductor never waned. The media cottoned on to this, and every year or so there was a report on the mechanics of it — if only to say now it is turning, now it is not and now it is about to.

I got curious about the kalo pori’s genesis some years ago but couldn’t go beyond a name here, a detail there. Aiding my query, a friend forwarded me a note from the British scholar Rosie Llewellyn-Jones. It came with a photograph of the pori as a work in progress. There she was, mouth on a trumpet held up lightly but resolutely, a wreath in another hand, robes clinging to a full figure, mighty wings waiting for the right backdrop to come alive, a foot on a dome and a human figure bent over it. Llewellyn-Jones wrote, “…it doesn’t give the name of the chap who’s actually doing the work.”

My search would have moved no further, but then came the pori’s centenary year and just like that the wind changed.

An image of Victoria Memorial minus the kalo pori Courtesy Victoria Memorial Hall

When Queen Victoria died in 1901, Lord Curzon was the Viceroy of India. He announced his plan to build a memorial to his monarch. The man who hastily sliced and diced Bengal did not rush with his dream project. Between 1905 and 1909 no actual work of construction was done. Instead, William Emerson and his team of architects and draughtsmen perfected the plan.

Victoria was the name of the British queen, it was also the name of the Roman goddess of victory. The figure of Victory was a common representation in Roman monuments and coins. In early Christian art, the winged angel replaced the winged Victory. The kalo pori was meant to represent the Angel of Victory. “British imperialists imagined themselves to be Roman, hence the borrowed symbolism,” said Jayanta Sengupta who is secretary and curator of Victoria Memorial Hall.

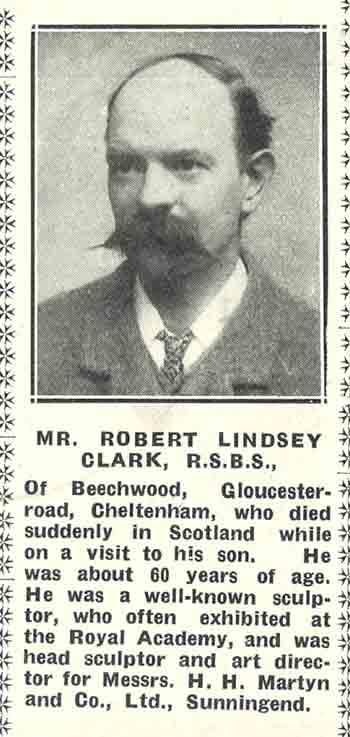

The obituary of Robert Lindsey Clark Courtesy Cheltenham Local & Family History Library

Most people credited a sculptor from Cheltenham town in England’s Gloucestershire with the creation of the angel. I got in touch with the Cheltenham Library and received two scanned news pages. The first was from The Echo dated February 1921. The entry headlined “Calcutta Queen Victoria Memorial” read, “Cheltonians... will be interested to know the large part played by a local firm in the art work.” The angel had been model-led and cast in bronze by H.H. Martyn and Co. Ltd. The second page, also from The Echo but dated June 1926, carried an obituary of a Robert Lindsey Clark who had been head sculptor and art director at H.H. Martyn. It said on behalf of the firm that he had worked on portions of the Calcutta memorial.

The Gloucestershire County Council shared with me an advertisement of H.H. Martyn from the 1920s; the 16-foot bronze angel was the lead visual and clearly its USP. But there was no mention of Clark on the flier; instead, it read — “Architect: Vincent J. Esch”.

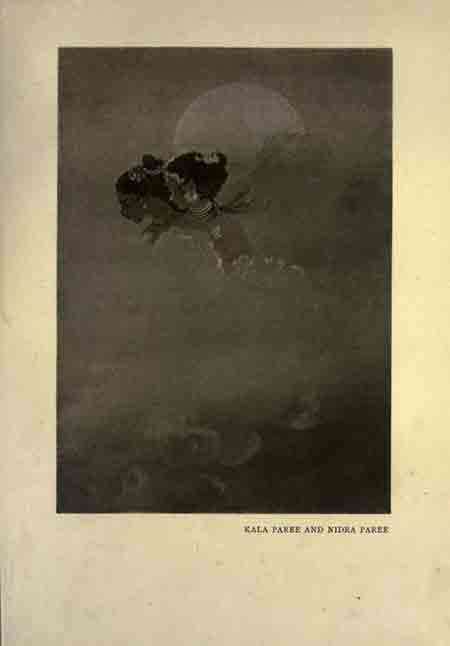

Kala Paree and Nidra Paree by Abanindranath Tagore in Bengal Fairy Tales Bengal Fairy Tales by Bradley-Birt

I wrote to the Cheltenham Local History Society hoping to get more details about the brief to Clark, perhaps his jottings. Jill Waller replied saying, “Sadly almost all the records of H.H. Martyn & Co. were destroyed, firstly by a bomb in World War II, and then when the works closed in the 1970s.” But I could refer to a book on the firm written by a great grandson of the founder.

The Best by John Whitaker confirmed that Clark had designed the angel, though his most famed work was not this but a bronze sculpture called The Broken Limber. An Italian, George Mancini, had apparently cast the angel into bronze.

Clark had been a member of the Royal Society of British Sculptors. When I wrote to them, Elle Arscott replied saying she doubted if George Mancini had been involved in the angel’s making as, according to the records, he did not set up his own foundry until the early 1930s. Later, Suzanne Lindsey Clark, daughter-in-law of Clark’s grandson Michael, told me, “It was actually George’s father Frederick Sr who created the bronze.”

H.H. Martyn engaged the Mancini family to work in the foundry “because of their special skills in the lost wax process; making the mould in plaster with a thickness of wax between the mould and the core”. In yet another email, Suzanne wrote, “I have attached a portrait photo of Robert as well as photos of the designing and making of the angel...” And there it was, the exact same puzzle piece photo with which I had embarked on this kalo pori chase.

Other gaps filled up. Sengupta had shown me a photograph of the memorial dated July 5, 1921, and missing the pori. And yet it was very much there in the photographs from the inauguration in December 1921. But Arscott had said the angel was shipped from Cheltenham to Calcutta in 1920. This meant that though the angel was in the city, it assumed its perch sometime between July and December 1921.

I would have stopped here, except that I found this nugget in one of the archival gems shared by Waller. A page of the British weekly The Graphic dated November 1920. Report 1 titled “Some Problems of the East” was about how despite her problems, India had much to offer “in the way of artistry”. There was a reference to the Bengal Fairy Tales (1920) by Lieutenant-Colonel F.B. Bradley-Brit, which Abanindranath Tagore had apparently illustrated “with most delicious charm”. Report 2 was an update on Victoria Memorial. Not caring for editorial logic, the olden page designer had stuck a photograph of the Angel of Victory in the middle of Piece 1.

On a whim — or was it a nudge? — I looked up the Bradley-Birt book and there it was, a wondrous illustration by Abanindranath. The full-page watercolour showed a charcoal horizon of the texture of dreams, soft with billowing clouds, a paper-white moon and side-profiles of two maidens dark of skin. It was captioned “Kala Paree and Nidra Paree (sic).”

Fairies have their ways, they work by suggestion.