Wearing a hoodie that reads "Future," Valeria Shashenok waves into the Zoom camera. She had arrived in the Italian city of Milan a few weeks ago, where she has settled in with an Italian family. Until she fled Ukraine, she hid with her parents in a basement in Chernihiv, a city in northern Ukraine near the border with Russia.

"My mother came into my room on February 24, and said: 'Valeria! A bomb has hit Kyiv and destroyed a building!'" Shashenok says. She and her parents reacted quickly. They packed the most important things and moved to her father's old office in the basement. At the time, he was running a restaurant in the building, and had just renovated the basement, installing a shower and toilets. Shashenok spent 17 days there. "It was very boring," the 20-year-old says, adding that she was lucky to have Wi-Fi and a smartphone.

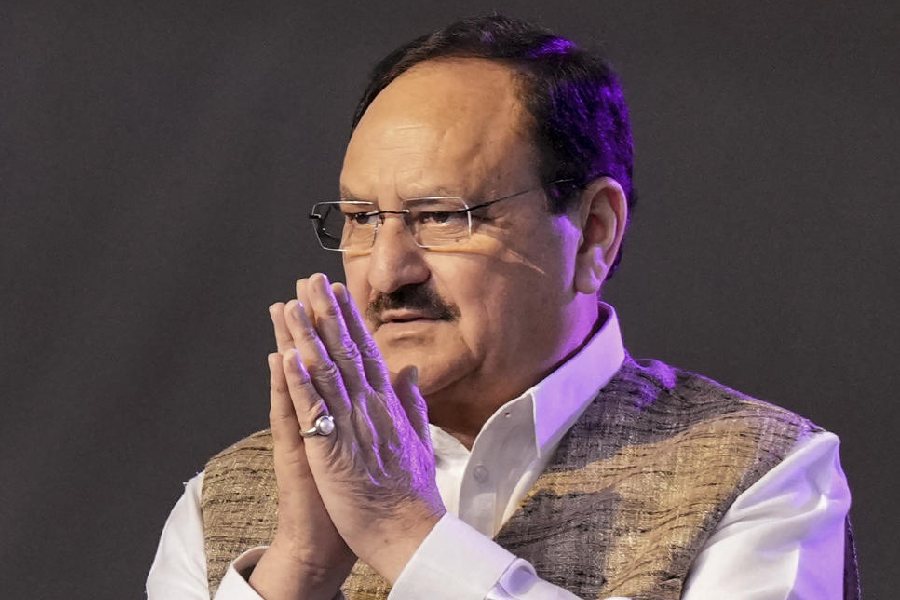

Valeria Shashenok now lives in Italy with a family Deutsche Welle

TikTok and the outside world

Shashenok is a digital native: a member of Gen Z who grew up with Instagram and TikTok. Social media was her window on the world. But then things changed: The world wanted to know what was going on in her country.

At the time, the phrase "things that just make sense in ..." was trending on the social media network. Participating users showed unusual things in their cities or homes that only made sense in the local context. Shashenok joined the trend and showed users her daily life in the bunker.

Using her sharp wit, she showed things that made sense only in a bomb shelter: using a hot-air gun to dry her hair, what breakfast looked like underground and how traditional dishes such as Syrniki — a type of pancake made with cottage cheese — could be prepared without a stove. Her videos met with enthusiastic response. The 20-year-old now has 1.1 million followers, and her most successful video has been clicked more than 48 million times.

Subtle black humor plays a central role not just in Valeria's videos; memes from Ukrainian channels have become popular in the wake of the war.

"I like black humor. It helps one get through absurd times," Shashenok says. "Humor is a part of our Ukrainian culture. People in Ukraine really believe that the war will end soon, that we will win. They want to stay optimistic — nothing else remains for them." And, thus, Shashenok jokes that life in an underground shelter also has its positive side: A lack of cow's milk now means that she is using oat milk as a healthy alternative.

Ukrainians have responded to the invasion with humor in nondigital contexts, as well. Large billboards stand on the streets in some cities bearing messages in Russian script that translate to "Russian warship, f*** you."

Escape from the shelter

After spending 17 days in the underground shelter and after Russian forces began intensifying their attacks, Shashenok decided to escape. Her parents remained in Cherniv while she arrived in Italy via Poland and Germany. She has been living with a family for a week now.

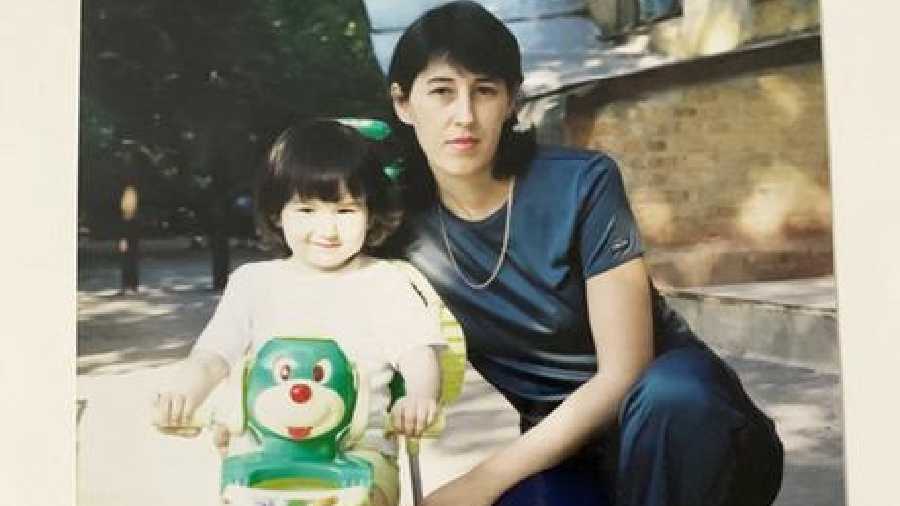

Shashenok as a child with her mother Deutsche Welle

Shashenok is in touch with friends and family in her home country. She speaks with her parents every day, more with her mother, less with her father. "He is so nervous," she says. "He has nothing to do all day and screams at me over the telephone, not because he wants to scold me, but because he is at his wits' end. He's losing it."

She's also in touch with Anton, a friend. He wanted to escape, too, but was unsuccessful. A law prohibits men aged 18 to 60 from leaving Ukraine. Anton has signed up for the army and is a guard at a military unit, Shashenok says.

At the end of March, Shashenok learned from her mother that her cousin was hit by a bomb and died from the injuries. "What is Russia doing in my country?" says Shashenok, who grew up speaking Russian. "I ask myself every day. Putin says he wants to protect us from the Ukrainian government. Excuse me, what? We had a perfect life: We don't want to be protected by Russia."

Shashenok has been documenting the war Deutsche Welle

Plans for the future

Like all Ukrainians, Shashenok hopes that the war will end soon. She wants to return. "I miss my country," she says. "When the war is over, I'll go back."

Starting this week, Shashenok is on a reading tour. Her book, "24. Februar: Und der Himmel war nicht mehr blau" (Feburary 24: And the Sky Was No Longer Blue), has just been published in German, compiling photographs and her experiences after Russia invaded Ukraine.

"I am dedicating this book to the Russians, in the hope that they will understand what they have done to us," she says. But she is not convinced herself. Some do not want to understand, while others are afraid to speak against it. But she wants to continue, and not only on TikTok and Instagram: Valeria Shashenok works with aid organizations in Cherniv and wants to use her popularity to raise funds to reconstruct her city.