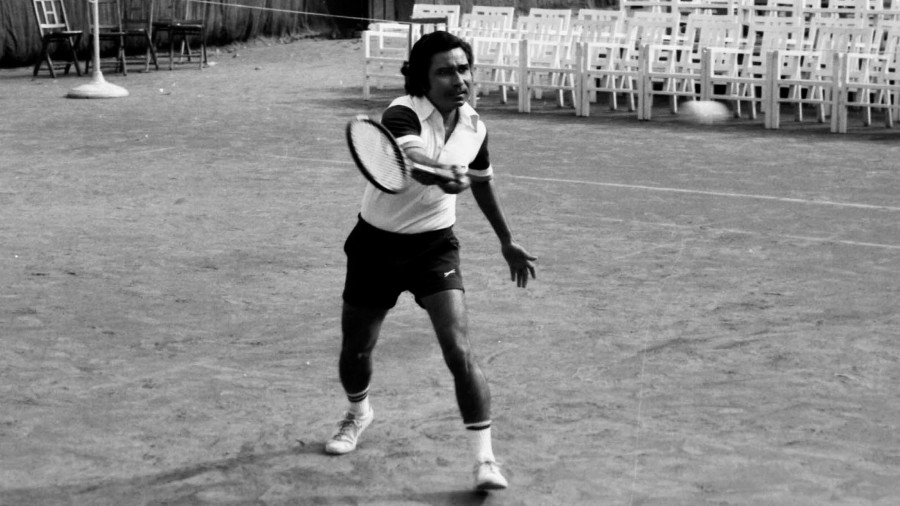

The Dronacharya... A diminutive man in crisp white tennis shorts and T-shirt.

The Dronacharya... Pleasant, amicable and witty; always with a smile on his lips.

The Dronacharya... A man transformed, the minute he stepped onto the tennis court, barking out orders to his wards, smelting iron from the ore.

That was Akhtar Ali. A national tennis and squash champion, a regular on the Indian Davis Cup team from 1958 to 1964, a national and Davis Cup coach for decades and a mentor to generations of tennis players.

And yet never considered worthy enough by the powers that be to be conferred the Dronacharya Award, he was “Akhtar Sir” to his countless protégés, and others who have benefited from his coaching and wisdom. He was their Dronacharya.

As Ali made the last journey from his residence at south Calcutta’s Lower Range Road to the Sola Ana Kabristan in Kidderpore last Sunday, accompanied by family and friends, tribute poured in — from Vijay Amritraj to Sania Mirza, from Mahesh Bhupathi to Somdev Dev Varman, from Ali’s own legendary peers such as Ramanathan Krishnan and Jaidip Mukerjea.

But one person was left speechless with grief. “I still can’t process that Akhtar Sir is no more. Give me some time please,” was Leander Paes’s first reaction when I spoke to him that Sunday.

No matter how close the two were, he was always “Akhtar Sir” to Leander. “Others I do call uncle, but Akhar Sir was always Sir,” said the 18-time Grand Slam champion, when we spoke a couple of days later, putting his relationship with Ali in perspective.

In the late 70s and early 80s, the Ali brothers — Akhtar and Anwar — used to hold regular tennis camps for kids. Leander held a tennis racquet for the first time when he was five and within a year or so was a regular at these camps. Now, so many years and trophies later, the 48-year-old Olympian claims he owes his passion for tennis to the Alis. “I used to spend a lot of time with Akhtar Sir. Our homes in Park Circus were literally within 100 yards of each other. I spent long hours with Anwar Uncle at Outram Club and with Akhtar Sir at South Club and Saturday Club,” says Leander.

He continues, “Akhtar Sir would peep out from the locker room to see if I was still at it after practising on Court 6 (against the wall) for more than an hour or so. He would check whether I was practising my forehands and backhands… I remember an incident at the Power Camp — I still have a picture of that — with all of us kids lined up at the net. There was Zeeshan (Akhtar’s son and former Davis Cup player) too. And Akhtar Sir was holding my hand and teaching me how to keep my wrist up.”

It was during these camps that Ali procured the Snauwaert graphite racquets for the trainees. With most players in India still playing with wooden racquets, a Snauwaert graphite racquet was known to be a prized possession for serve-and-volley players.

Says Leander, “Dad bought two of them for me. They had a crazy shape but were designed to help in playing the volley. I was about 10 years old then. Nine months later, I shifted to another brand. We got four racquets and Dad thought I was sorted for the season. But those days racquets did not have fancy grips; they would get wet and slippery. We would keep sawdust in our pockets and use it to dry the leather grip while playing. I brought all four of my racquets to a practice session with Akhtar Sir. You won’t believe, within an hour all four brand-new racquets had slipped out of my hand and crashed at various places in South Club. Each one broke beyond repair. Akhtar Sir was speechless.”

The Calcutta South Club was where the young Leander was able to rub shoulders with legends of Indian tennis, before Vece Paes, himself a hockey Olympian, realised his son’s potential and packed him off to the Britannia Amritraj Tennis Academy in Madras. But Leander carried South Club and Akhtar Sir within him.

He tells me, his voice hoarse with emotion, “Akhtar Sir taught me how a not very talented tennis player, growing up in the 80s with not much infrastructure, could use his god-given gift of physical fitness and mental strength and become a champion.” He adds, “Akhtar Sir taught me how to volley. I am basically a serve-and-volley player and he was instrumental in giving me the most potent weapon in my arsenal. Without that I would not have been half the player I became.”

Pause, and he goes on. “Every time I step into Saturday Club when I am in Calcutta, I remember Akhtar Sir holding my hand and showing me how to hold my wrist up while volleying. That has always remained with me. No matter how hard the ball was coming at me, I always remembered to keep my wrist up on my volleys.”

It was much later that Leander realised why Ali was so keen on him perfecting his volley. He says, “As a little boy I was more into football. Akhtar Sir recognised my athleticism and mental aptitude. He knew what kind of game would suit me.” And that perhaps was Ali’s trademark — a perfect strategist who could identify the strengths and weaknesses of his players and their opponents and plan accordingly to win a match. Even his illustrious peers such as Ramanathan Krishnan, Jaidip Mukerjea and Naresh Kumar have always acknowledged this quality of his.

What endeared him to his mentees was his nature. “Akhtar Sir outside the tennis court was very jovial, very kind, very caring and loving. He would drop me home on his Lambretta scooter. Every training session he would buy me ice-cream sodas. He was always patient with my endless questions... But on court, he was a tough taskmaster. He would push me harder than most others. I once asked him, why are you so tough on me? And he said: ‘Because you have the talent to be one of the greatest ever.’

The simplicity of that explanation, the way he took time to make a 10-year-old kid understand why he was tough on me...” For the nth time in our conversation Leander cannot continue at a stretch. Seconds later he adds softly, “...that was Akhtar Sir.”

Akhtar Ali’s story is phenomenal. Leander says, “He grew up with not many opportunities.” Indeed, Ali was keen to eke out a better life, and used sports to reach his goal. He told me once how he used to work as a ball boy at South Club while learning tennis. From such beginnings he went on to become one of the finest tennis coaches. Leander interjects, “There was a time when Maharani Gayatri Devi of Jaipur started to look after him. She invested in him. He used to teach her squash at her palace. I think he himself understood that he would be a better coach than a tennis player and so he retired early.”

At some point we start talking about how the precocious 10-year-old started playing Davis Cup matches and Grand Slams. Says Leander, “For every Davis Cup match, I used to run my strategy by Akhtar Sir.”

One such was the India vs Croatia match in 1995. In New Delhi, when Leander took on Goran Ivanisevic, there was hardly a soul who thought he could win. But he scripted a stunning upset to win 6-7, 4-6, 7-6, 6-4, 6-1. India won the tie 3-2.

The previous year, India had clashed with South Africa in a World Group qualifying tie in Jaipur and narrowly lost 2-3. But for Leander, it was during this tie that he found out another quality of Ali as coach. He says, “I had won the opening singles, but we lost the second. In the doubles, Gaurav Natekar and I lost a match we should have won. I was angry with myself and needed to vent before taking on Wayne Fereira, then a top-10 player. Akhtar Sir had watched him practise and told me how to play him. There was a squash court at the Rambagh Palace where we were staying and I just wanted to run around playing squash, to sweat it out and get my rhythm back.

“During Davis Cup you are not supposed to play any other sport or take risks that may lead to injuries. But Akhtar Sir realised what I needed and kept this a secret. He understood I needed to sweat it out. Next day, I played Wayne and I won. He understood the human spirit. He was willing to bend a few rules for it.”

Ali was always eager to pass on knowledge to Leander. In the 90s, when the game changed to being a more power-oriented sport, he advised Leander to change his footwork and taught him to kick serve. “He was like a beacon in my life,” says Leander.

And when things started getting a little rusty for Leander, when tiredness started creeping into his tremendously long career, it was again his Akhtar Sir who egged him on. Says Leander, “In the last few years when I was getting rather tired of the rigorous hours of travel, of hotels and airports and flights, Akhtar Sir would say: ‘You’ve still got so much in you. Mentally you are fit, keep pushing your body, keep getting the world records, keep pushing your mind. You need to do this to prove to young Indians that they can be champions too.”