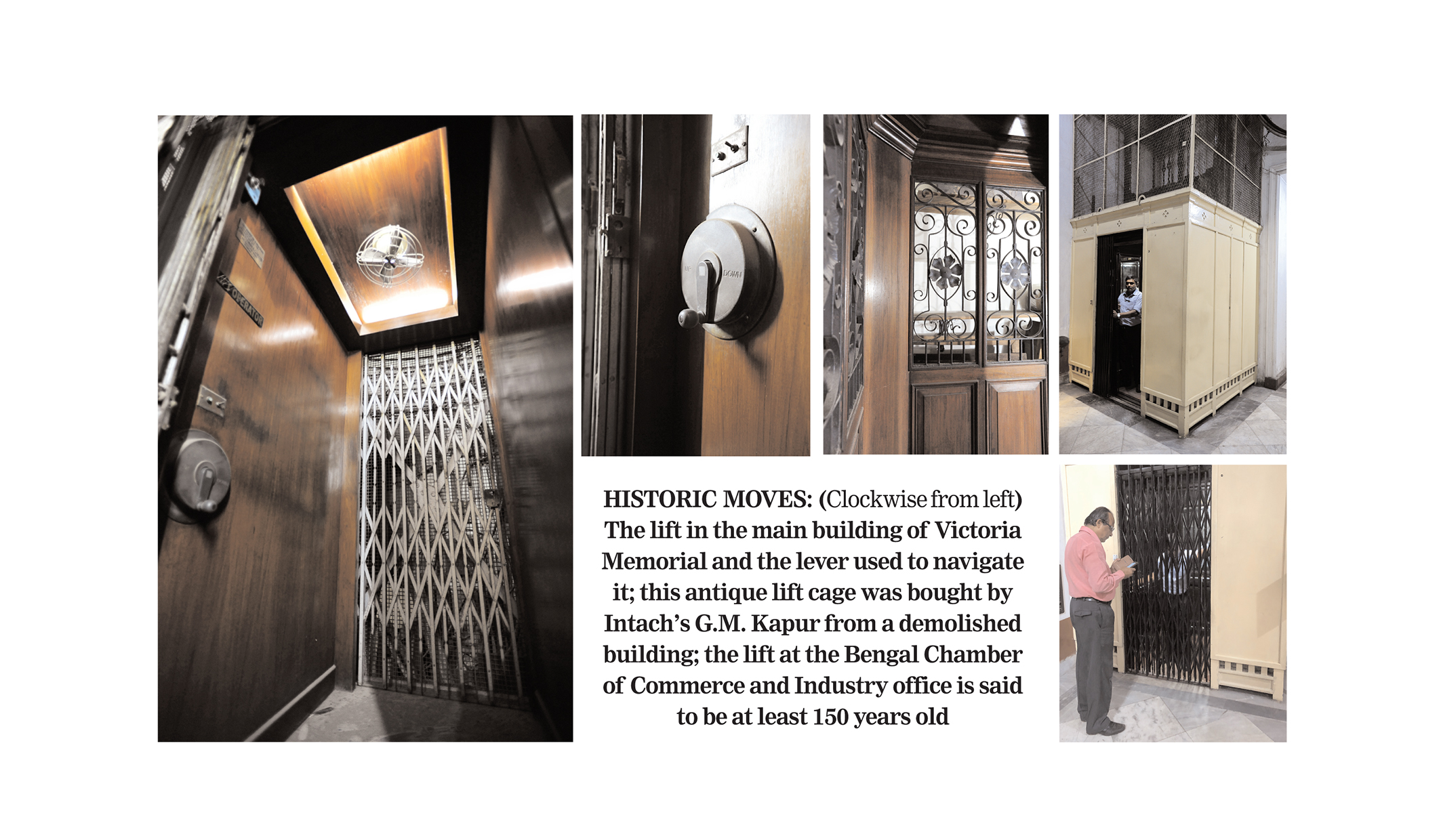

When you enter the Bengal Chamber of Commerce and Industry (BCC&I) office in central Calcutta, a majestic staircase looms into view. But it pales in comparison to the three ancient lifts that face it. Waiting for the lift, you can see loopy wires through the collapsible iron gates or look up and admire the lift cage that goes right up to the roof — the fourth floor to be precise. H.S. Das, who works here, does not know when the lifts were installed but is sure that they are very old — “at least 150 years”.

The interiors of the elevator are all wood; a dark reddish-brown. There are steel grab rails on all three sides and a rusty fan overhead. There are three long mirrors around the lift. The liftman inserts the keys into a gap and moves a lever. There are no buttons, no blinking lights. The direction in which the lever is pushed — up or down — is what determines the lift’s movement.

In the book, Those Noble Edifices – The Raj Bhavans of Bengal, Jayanta Sengupta writes that Calcutta’s oldest lift is in Raj Bhavan in B.B.D. Bagh. It is most likely the oldest in the country too. An excerpt from the book reads thus: “Lord Curzon introduced — electric lights in 1899, fans a year later, fixed baths in place of cumbersome wooden tubs in 1905, and — sometime in between all these — an electric lift as flimsy as a gilded bird cage, which is still in use in the South-west wing of the house.” Urban legend has it that when the late Nurul Hasan was Governor of Bengal, the man of uncommon girth never fitted into the vintage people-mover.

Sengupta is also the director of Victoria Memorial. The main building of the iconic structure, the one with the museum, has a lift from the 1950s. It travels a single floor though. The lift cage is still intact but the lift has not functioned in the last two years. On the steel-grey collapsible gate hangs a signage: Lift Under Repair.

Balaram Ghosh, who currently works as a peon but used to be a liftman from 1995 to 2017, talks about maintenance issues and how these lifts are difficult to repair. He fits the lever into a coin-sized hole and demonstrates how it would function. He switches on the lights of the lift and suddenly the dark brown wood comes alive.

According to conservation architect Partha Ranjan Das, some of the other places that still retain these quaint lifts are the Writers’ Buildings and the state Legislative Assembly.

It seems, around the 1930s and later, Otis Elevator was one of the best known names in the trade. “I have seen Otis lifts in some of the old buildings but post the restoration, some places have removed the name,” Das says.

Architect Abin Chaudhuri rattles off names of lift manufacturers — John Fleming, Marriott & Scott of London and so on.

It appears that none of these lifts was manufactured in India. The practice was to have the entire body shipped from the US. Das says, “The one at the Writers’ Buildings would be a little more than 100 years old. Before that, electricity was not easily available. The people at the Calcutta Electric Supply Corporation (CESC) would enhance the electrical load wherever these lifts were installed. Buildings had to take special permissions from the CESC to instal them.”

Most of these lifts have a machine room on the topmost floor. According to Das, if the machine is replaced, the cable, lift cage, everything has to be replaced. “If all of these go, nothing remains of the old lift other than its heritage value,” he adds.

These lifts weigh about a tonne or more. They are heavy as they are made entirely of steel. The lifts that climb one or two floors only — like the ones at Raj Bhavan and Victoria Memorial — are easier to maintain.

At some point, every building in and around Park Street area had these vintage lifts. Seventy-year-old Mahendra Rai is the caretaker of one such prime property, Park Mansions. He reminisces starting out as a liftman here. Park Mansions had and still has five lifts. “Those old lifts functioned on direct current (DC). In the last 10 years, it has all become automatic. Lifts now function on alternating current (AC),” he says.

At the BCC&I office, administrative staff Sanjoy Mukherjee unlocks a dark room with a big green bulb. The bulb is a rectifier — it converts AC to DC so the lift can function. Apparently, the CESC had decided to stop supplying DC power to Park Street and, because these lifts cannot function on AC, most of them had to be replaced. Mukherjee recalls, “Lohe ke bhaav mein bech diya sab lifts ko... The lifts were sold at the price of scrap iron.”

Agrees G.M. Kapur, the convenor of the West Bengal chapter of the NGO, Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage or Intach, “Except for the motor, there is nothing in the mechanism that can be sold for a good price.” Ten years ago, Kapur picked up a lift cage, carved grills, detailed engravings and two doors — one for entrance, another for exit — et al for Rs 3,000. “The building in which it had been installed was demolished. This lift will easily be a 100 years old,” he says. Today, the teak-wood lift cage — another Otis — lies in one corner of his residence-cum-office in central Calcutta.

Another building on Park Street, Queen’s Mansions, has retained a 150-year-old lift cage and the grills, but has done away with the interiors. The levers have been replaced with buttons.

Similar is the office of the West Bengal State Archives. Lakhan Chandra Rai, 55, used to operate the lift from 1999 till some years ago — when the new lift came into place. In the old days, the lifts had to be manned round the clock, and without a liftman no one could use them. “We would sit inside all day. Two of us would alternate every two hours. Lifts these days do not need people like us,” he says. In those days of constant power cuts, it was the liftman who had to leap to the rescue if the lift got stuck between floors.

The few remaining old lifts are gasping to stay alive. BCC&I’s Mukherjee says it is difficult to find people who know how to repair them. The ones who currently do the repair work for BCC&I have been in the business for three generations. Even though the golden rusted signage inside the lift says it can take a load of 1,050lb (over 476 kilos) and the mentioned number of people is seven, the lift can’t take more than four people now. Another signage nailed inside the lift identifies the makers as Waygood-Otis Ltd, Liftmakers, London.

Says Kapur, “Many heritage buildings did not have lifts. But a lot of these buildings are now being retro-fitted with new-age lifts. The Tollygunge Club recently got one. It was necessary for disability access and elderly people, but the moment you add something like this, the heritage value is affected.”

From the sound of it, the only way the city’s vintage lifts are going is all the way down. Take a ride while you can.