Jhandi, a small village at a height of 6,200 feet in Bengal’s Kalimpong district, is known for its breathtaking view of the Kanchenjungha as well as the Mahananda Valley spread below it. But Samit Saha did not make the long trip to Jhandi from Calcutta for either of those sights. He was there that chilly evening at the end of October for a third view that Jhandi provides — that of the clear night sky sparkling with stars.

Every few months, Saha, a middle-aged civil engineer in the field of infrastructure, quits the city for a few days to keep his date with the stars. On that trip to Jhandi, Saha stayed up two nights clicking thousands of frames of the Orion galaxy. An endeavour that requires dark skies far away from the light pollution of the city, preferably at a high altitude for clearer skies. It means chilly nights, sacrificing sleep, immense patience and the equanimity not to be overly disappointed by sudden bad weather.

How did Saha pick up such a demanding hobby? “You can blame the pandemic,” he says. Saha was stuck in a remote region with nothing to do, so he rustled up a DIY telescope to watch the night sky and joined other enthusiasts on a Facebook group.

It is to show them what he was seeing that he started clicking pictures. “I was using my mobile phone but some of the Milky Way photos came out exceptionally well,” says Saha. He was hooked.

By Basudeb Chakrabarti in Singalila National Park in Nepal. The Sagittarius arm of the Milky Way can be seen with naked eyes from dark sky locations. Captured with Sony a7iv, Samyang 14mm lens on a SkyGuider Pro Camera Mount

He continues, “When you take a picture of the stars, you are actually capturing a slice of time. Because the photo holds evidence of what happened in space over that period of time.” There was also the feeling of just how insignificant humans are

in the larger scheme of things. “Astrophotography puts us in our place,” says Saha with a laugh.

Astrophotography, also called astronomical imaging, is about taking pictures of

the sky to capture celestial bodies or events such as meteor showers, eclipses or a blood moon.

Taking photos is, however, only half the battle won. It is the post-click processing that turns multiple frames stacked together into that sharp, awe-inspiring image of the Milky Way, meteor shower or star trail. All astronomical studies these days are based on astronomical imaging. Astrophotography, however, usually refers to the craft practised by people like Saha who photograph the sky just for the love of it.

Basudeb Chakrabarti, 40, has loved looking at the stars since he was in school. Like Saha, he too travels to keep his date with the night sky every few months. Inciden-

tally, he is an electrical engineer by profession, responsible for lighting up the state. When pointed out that it is his own handiwork — light pollution — he is escaping from, he laughs.

Chakrabarti too started indulging in his hobby when he found time on his hands during the pandemic. Now, he makes time for it. “Astrophotography has helped me meet people I never would have otherwise. Some of them are now friends,” he says, recounting his time in Yusmarg in Kashmir when the sky was a photographer’s dream but the cold would have frozen him solid if the local youth who had set up camp further down the hill hadn’t invited him into their warm tent.

The post-click processing is just as fascinating for Chakrabarti. What processing basically does is take multiple frames and merge them into a single, striking one. And so interested is Chakrabarti in the magic processing imparts that he used frames taken by telescopes — these can be found on the Internet — and turned them into exceptional photographs.

His partner in crime was Soumyadeep Mukherjee, linguist by education and photographer by passion. A look at Mukherjee’s Instagram page will show his exceptional photography skills and the variety of subjects he likes to look at through his camera. Not having much to focus on during the lockdown — which caught him at home in Calcutta — he decided to photograph the sun. Thus, unknowingly, began his journey into astrophotography.

By Soumyadeep Mukherjee at Pangong Tso Lake in Ladakh, situated at an altitude of 14,000 feet. The Sagittarius arm of the Milky Way is visible over the Heritage Camp tents. Captured with a Nikon Z6ii and Tokina 16-28mm lens

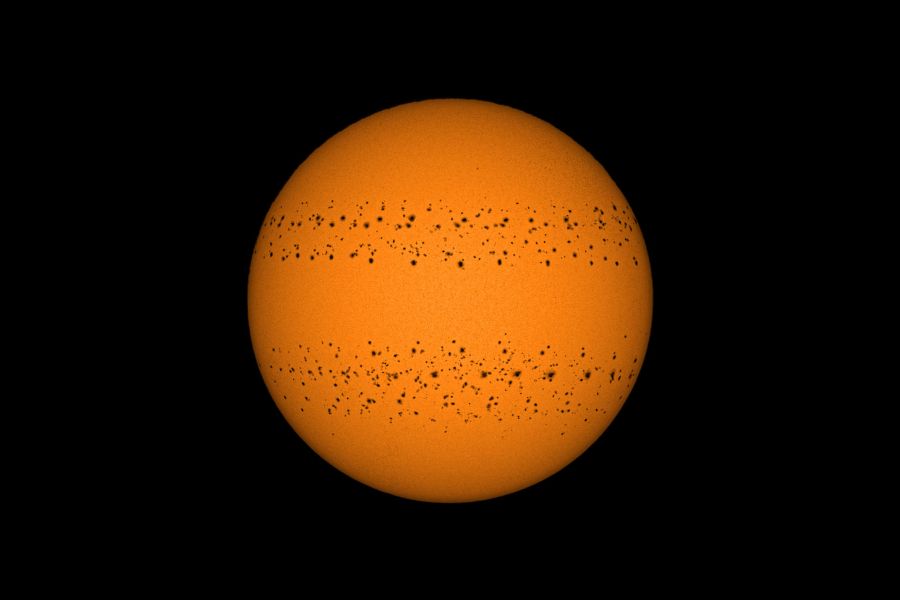

“It is easiest to photograph the sun and the moon from a city. It is possible to photograph the stars too but for that you need sophisticated equipment,” says Mukherjee, who ended up photographing the sun every day for a little more than a year. Then he processed 365 frames into one photo showing sunspots that appeared through the year and entered it in the annual Astronomy Photographer of the Year contest held by the Royal Greenwich Observatory in the UK in 2022. His photo A Year in the Sun won first place in the solar category.

That seems to be another draw for astrophotographers, or perhaps it is their motivation to do better. They take pride in talking about photos that were published in astronomy magazines or in websites such as Nasa’s. They are not as forthcoming about photos they found most challenging to take or that most appeal to them.

“All photos are difficult to take. The very nature of astrophotography is challenging,” says Chakrabarti. Saha talks about the cold and the disappointment of trekking for hours to reach the perfect place for a shot only to have clouds to obscure the view when the prediction was clear skies.

Saha and Chakrabarti seem to prefer to click stars while Mukherjee prefers composites. Apart from a year of the sun, he has also produced a year of the full moon, of Venus coming out from behind Jupiter using multiple frames in the same picture. The Venus photo was Nasa’s Astronomy Picture of the Day in March 2023.

(L to R) Astrophotographers Goutam Dey, Samit Saha, Soumyadeep Mukherjee and Basudeb Chakrabarti. Photo courtesy: Astronomads Bangla

Saha, Chakrabarti and Mukherjee — along with busy healthcare professional Gautam Dey — founded a group, Astronomads Bangla, in 2020. They had first connected on a stargazers’ group on Facebook during the lockdown and strengthened their bonds when all of them turned to astrophotography. But that is not the reason they came together to form a group — Astronomads Bangla was formed by these four because they were the only ones who made it to the first scheduled meet-up on their stargazers’ group, held before the second lockdown. They eventually started a website when they realised that they wanted to share their love of astrophotography with others. “It is our way of giving back,” says Mukherjee. “After all, we would never have learnt this much about astrophotography this quickly without the kindness of random strangers on the Internet.”

They hold workshops, host astrophotography trips and, since 2023, have been holding the annual Aperture Indian Photographer of the Year competition. In January, they also held an exhibition of the 30 best entries at the M.P. Birla Planetarium.

“This is just our humble attempt to popularise astrophotography,” says Saha. “Scientific thinking is the need of the hour,” says Mukherjee. “When they think about stars, we don’t want people to link it to the impact on their astrological chart but to the fascinating science of the universe.”

Big dreams. But then they are aiming for the stars.