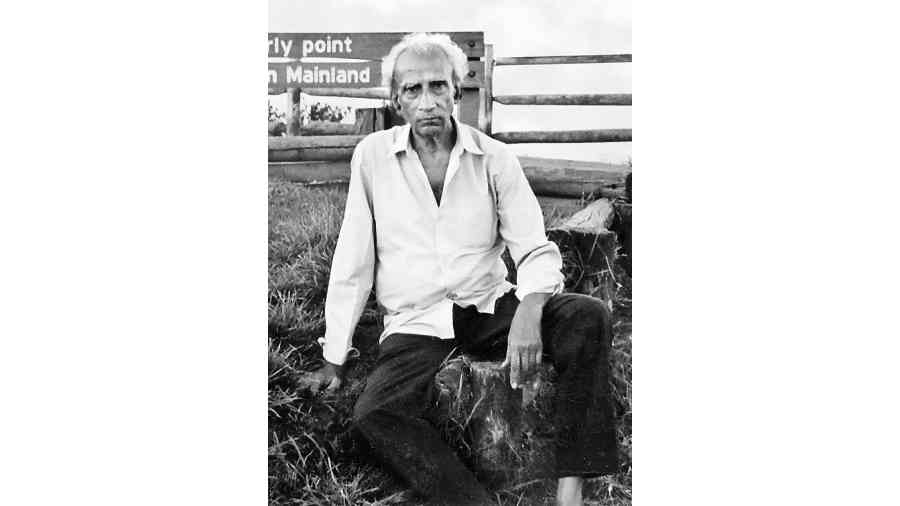

Rajen Bhattacharya is variously known in the Rajpur-Sonarpur area of Bengal’s South 24-Parganas as Borda, Boromama, Bodojethu and Rajenda. His essential claim to fame would be the Nandan Milan Bithi Club that he founded in the 1940s.

“Borda had wanted to play football from the time he was seven or eight years old,” says Pranab Bhattacharya, who is his younger brother by 20 years. He continues, “Those days this area was but a wilderness. The only club in the vicinity, the Harinavi Sporting Club, turned Borda down. There were other sporting clubs, Baikunthapur, Sonarpur, Rajpur, but those were quite a distance away. That is why when Borda came of age, he decided to start a club in his own locality that would create opportunities for the youth who wanted to make a career in sports.”

Today, they might have achieved notoriety, but the neighbourhood or para clubs started to come up in Calcutta from the beginning of the 20th century, possibly as a reaction to the elite club culture of the British. The number of such “native” clubs before Independence is not known as many were not registered. In 1947, there were about 1,500 clubs in Calcutta. Today, there are 43,000 registered clubs across the state.

Many of these clubs played a part in the freedom struggle. “But our Nandan club had no political impetus,” says Pranab. But yes, Bratachari activities were taught here. The club was also involved in social work. During the 1950s when the state was reeling under severe food shortage, club members distributed milk free of cost to pregnant women and children. Borda also distributed sewing machines.

In the early 1950s, the club moved from the broken cowshed that housed it and into a concrete structure. The plot was a gift from a local by the name Dinu Banerjee. The money for the single-room structure came from his parents, but the major contribution came from Borda himself. Says Pranab, “We have grown up hearing our mother complain about how Borda emptied the house of essentials at the slightest opportunity to well equip his darling club. Borda would hardly come home for his meals and mother would say that the club was the root cause of all evil.”

Pranab says he and his nine brothers and sisters grew up hearing stories of his schooldays when he would never finish his exam papers. “Khela aachhe,” he would tell his teacher and leave the examination hall. Because of his deep attachment with the club, Borda’s father sent him away to Bilaspur — then in Madhya Pradesh — for further studies. He completed his mining engineering degree and he was also selected for a training course abroad but his grandmother did not allow him to go. Pranab says, “That might have been a turning point in Borda’s life.”

If till now Borda’s life was centred on the club, in the years to come, he and the club became one and the same.

“Nobody in the family knew that Borda, who had started working in Bilaspur as a trainee in a colliery, would send money to Debuda, who was the co-founder of the club. It is with this money that the club got its only room and got its registration done,” says Pranab. Soon after, Borda got a job with a nationalised bank and shifted to Raiganj in Bengal’s West Dinajpur. When he returned to Calcutta it was the mid-1960s.

Borda remained a bachelor. He would either be on the field playing or coaching young players or he would be travelling. Pranab says, “We never knew anything about his plans. He would suddenly go away for a fortnight or more. Later we got to know that he went trekking to Roopkund, Amarnath, Pindari Glacier, Kalpa, Tong, Char Dham, Mani Mahesh, all of the Northeast, Kathmandu and so on.”

But wherever he went, he would come back to the club. He kept working for it. The club’s golden period stretched from 1970 right up to the mid-1980s. Coaches from Mohun Bagan would visit the club and groom young people; Nandan Milan Bithi played against other Calcutta clubs; there were practice sessions in the Maidan.

The club did not remain a place for sporting activities alone. In the 1960s, Borda opened a primary school. It catered to the children of daily wagers and domestic help living in the neighbouring areas of Dhopapara, Moylapota, Goylapara, Swarnokarpara, all within a three-kilometre radius of the school. “He did not charge any fee and he had no source of funds either. But there were people who wanted to lend their service. Locals such as Dilip mastarmoshai, Padmadidi, Rathinda, Probodh Bose, would teach beyond their formal work hours,” says Pranab.

“The school was expanding slowly. When in 1975, the school got its sanction from the government to start Class IV, the CPI(M) forced him to give over the school to the government. They threatened, attacked and beat up the teachers when Borda did not comply. He finally relented when he was told that the government would not appoint teachers if the school was not registered as a government-run institution.

But Borda did not give up the library. “He and Debuda had started the library in the 1960s. Children, youth and the elderly could become members for a fee of four paisa a month.” Dulal Bhattacharya, a local, used to be the librarian. Borda paid him a nominal remuneration from his pocket. A few years after the government took over the school, there was a need to register the library separately.

Borda retired from his job in the 1990s and spent his entire retirement benefit on an indoor gymnasium for the club. But when he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, he could not fund his own treatment. The 84-year-old had no complaints though. Till the last day, his only question was, “Is all well with the club?”

Rajen Bhattacharya died in 2017, but his beloved club lives on.