He kept a diary, I knew. But that he had Indian journals was a revelation to me when I came upon the unpublished journals in Houghton Library (the primary repository of rare books and manuscripts of Harvard University in Massachusetts, US) through serendipity six years ago,” says Anindyo Roy, a retired professor of English literature. The “he” here is English limerick writer Edward Lear.

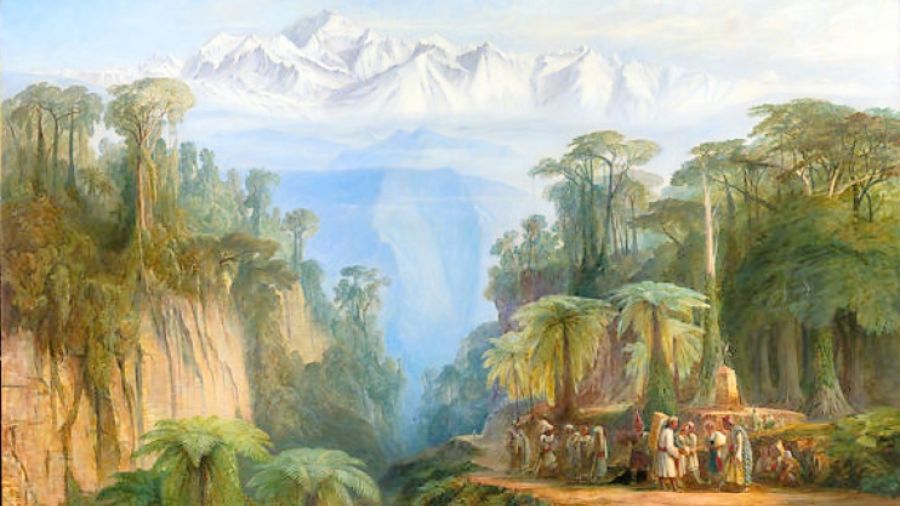

Roy, who used to teach at Colby College in the US, tells The Telegraph that Lear was in India for 13 months. His mission: to paint the Kanchenjunga as he saw it from Kurseong in West Bengal.

Lear was a much-travelled man. Before he reached India in 1873, he had been to Albania, Jerusalem, Palestine, the Middle East, the Balkans. He was a gifted artist too, with a special interest in ornithological drawings and animals, and as he travelled, he sketched.

The trip to India was different from Lear’s other travels — it was a commissioned trip. He had been invited by the then viceroy, Thomas George Baring, who was fascinated by the view of the eastern Himalayan ranges and wanted drawings of it for his personal collection.

Lear did the sketches and when he went back to Italy, two paintings based on the sketches. “But I find Lear not in what he painted or wrote. It is in the gaps and silences of Lear, the things that he mentions but does not explain,” says Roy.

The journal starts with a description of Bombay. From Bombay to “Jubbulpore”, from Jabalpur to Kanpur to Allahabad to Benaras. Lear writes about temples, palaces, culture and religion. His entry from Gwalior reads: “The view thence of the fort of Gwalior and that of the city below with all its houses, vastly like that of the Acropolis and city of Athens height... I drew, and drew.” He goes to Munger and Arah in Bihar, Pune and Goa before moving to Madras.

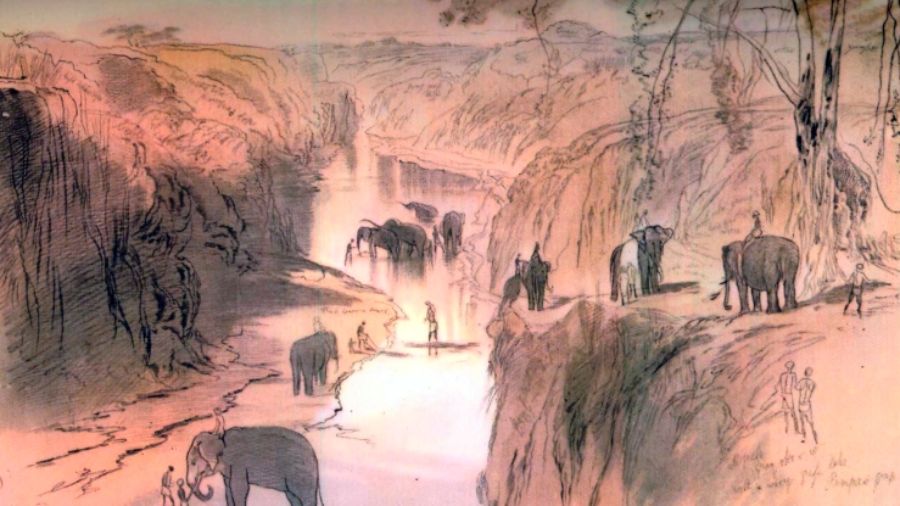

Assiduous jotter that he is, Lear seems to put down on paper anything that is of novelty or interest to him. Quaintly spelt Hindi phrases; descriptions of sounds — of the horse cart, the mourning notes from a funeral procession in Agra, the late-night singing at Fatehpur Sikri; the first sight of elephants. When he finally sees the Taj Mahal, he is overwhelmed by so much detail that after a while he does not sketch it at all. He writes, “Henceforth, let the inhabitants of the world be divided into two classes — them as has seen the Taj Mahal; and them as hasn’t.”

Lear’s painting of Kanchenjunga. Artwork, courtesy Edward Lear’s Indian Journal and The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Most part of Lear’s journeying was by train, but he notes that he took the jampan, a hand-pulled carriage, when he went to Shimla from Kalka. He took a horse cart from Coonoor when he travelled through the coffee plantations. In Calcutta, he travelled from Barrackpore to Tollygunge on a pullcart and walked down to Eden.

Throughout the travelogue, when it comes to the scenery and birds, Lear’s writings are full of keen observation, curiosity and scientific temper. But he is not as interested or taken with the people and their customs. Lear cribs about the tea and food right through his travels and himself writes about his intemperateness. Here’s an entry: “Health all wrong. Impossible to get any tea before 7.30... could eat nothing but a piece of toast, ‘made dishes’ not suiting me o’mornings. Cross, unwell and wretched.” It is at first difficult to imagine that this is the creator of The Owl and the Pussy-Cat and other nonsense verses. And then the possibility becomes clear that perhaps not all the nonsense is toothless.

Some would say the possibility turns to certitude with The Cummerbund, one of Lear’s nonsense verses composed during his India travel. It goes, “She sate upon her Dobie/To watch the Evening Star/And all the Punkahs as they passed/Cried, ‘My! how fair your are!’/Around her bower, with quivering leaves/The tall Kamsamahs grew,/And Kitmutgars in wild festoons/Hung down from Tchokis blue.” Researchers claim The Cummerbund “mocks Anglo-India jargon”, though you might need a Hobson-Jobson dictionary to decode that one.

Speaking of the Hobson-Jobson dictionary, Roy talks about how in Tanjore (Thanjavur in Tamil Nadu) Lear meets Judge Burnell, who had collaborated with Henry Yule in writing the dictionary. Burnell was at the time in charge of the Tanjore Museum and he was putting together his work on the erotic literature of India.

Finally, Lear reaches Kurseong. He writes: “So very remarkable an Oriental view I have never seen... a perfectly magnificent specimen of eastern landscape, most difficult to reproduce on paper, but wonderful to contemplate.”

Roy has just finished writing a novel based on Lear’s Indian journey. He won’t divulge details but he does say this: “Lear was not happy with the watercolours he found in the shops of India. In my fiction, I have allowed him the liberty to create colours from natural flowers; bright, luminous ones so that he can recreate and reproduce what was ‘wonderful to contemplate’.”