The Digital Arts Festival, DeConfine, curated by Media Art South Asia ended some months ago. But should you visit the website, you will come across a segment labelled “Featured projects”. Here, amidst a clutch of names from Pakistan, Bangladesh and Bhutan, you’ll find a series of digital illustrations by Reya Ahmed under the name “Women’s Worlds”.

Reya Ahmed. Resident of Calcutta. Currently in London, UK, where she is a student at the University of the Arts.

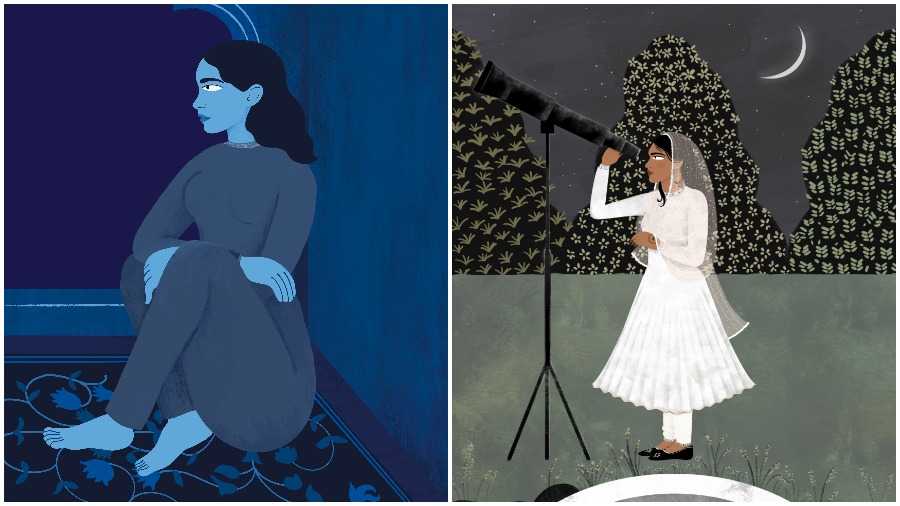

Bold colours, detailed portraiture, gardens, flowers, a hint of a certain kind of setting — mosques, palaces, white marble — and of course, human forms frozen mid-life. The art grammar of Mughal and Persian miniatures is so overwhelmingly familiar in these parts even to the non-art connoisseur that it takes about a second for the mind to grasp what the eye embraced at first glance.

The technique is a decoy, a Trojan horse pregnant with rebellion.

The artist has actually used the familiarity of miniatures to challenge the very male world order the miniatures codified and celebrated.

Though Mughal miniatures existed from the ninth century, it is believed that the art form came into its own in the early 1500s. When Humayun returned to India after spending some years in Persia — he had gone there to take shelter and seek military help — he brought home with him two Persian painters. In his book Mughal Miniatures, J.M. Rogers writes that rather than help a dying man who asked for aid, Jahangir would have his painters take a portrait of the man’s emaciated face. Maurice S. Dimand writes in The Emperor Jahangir, Connoisseur of Paintings how during his travels to Kashmir and other places, Jahangir was always accompanied by 2-3 artists who recorded interesting incidents.

Reya’s Moon Song shows two women — one sitting with a flower in one hand, the other hand resting on the back of the second woman, whose head is on her lap. Another work titled The Truth Untold could have been the balcony scene from the most famous sequel Shakespeare never wrote.

Reya tells The Telegraph, “I became fascinated with Indian and Persian miniatures during the pandemic — how a single painting told the whole story of an event in history. I was also curious about the role women played in these contexts and that is what I chose to explore.”

The overwhelming representation of Mughal miniatures might have been male but there were miniatures that portrayed professional women in the zenana and court and also commoners. In the paper “Representation of professional and working women in Mughal miniature painting (16th-18th century)”, Najma Khan Majlis writes about miniatures from Akbarnama that portray women as labourers employed in the building of Agra Fort and Fatehpur Sikri. There are representations of women acrobats, musicians, and one miniature from Jahangir’s time shows a woman artist “sitting with a sketch board on her knees, busy painting with her brush”. The artist is wearing a sari.

One of Reya’s illustrations is titled Mahila Masjid. The words in parenthesis suggest a nod to Shaykh Zadeh’s “Scandal in a mosque”; the word used is “a recreation”. Now, Zadeh was the pupil of the great Bihzad who lived in Herat in the 16th century. (The same Bihzad of whom a poet wrote: “Is not the beloved’s slender waist thinner than Bihzad’s brush?”) “Scandal in a mosque” or “Incident in a mosque” is one of Zadeh’s signed paintings found in a folio of Persian poet Hafez’s Divan.

Much has been written about Hafez’s “libertine tone and his railing against figures of religious authority”, but it is more likely that Reya chose to re-create this work only to overwrite the all-male cast. Mahila Masjid shows only women.

Around the time Reya was creating most of this oeuvre was also when the Shaheen Bagh women’s protest was happening in Delhi in response to the passage of the Citizenship Amendment Act. It was also the same time when in the grounds of Park Circus, Calcutta, which happens to be Reya’s para, Muslim women took up the “halla bol” and “azadi” chants in solidarity with Shaheen Bagh. Reya says, “At the time (2019-2020), we were having important conversations as a country and it was refreshing to see a lot of Muslim artists expressing their personal experiences and identities through art. It empowered me to do the same.”

By Reya’s own admission, her choice of miniatures as a visual vehicle was initially motivated by the style but later on, “became more personal”.

Is there a particular work in this series she’d like to draw attention to? Says Reya, “I think my earliest one from the series, The Perfect Body. It’s a re-imagination of another famous painting.” Indeed, Belgian surrealist René Magritte’s Attempting the Impossible shows a man in a suit painting a woman on to thin air instead of a canvas. The Perfect Body shows a woman in salwar-kameez painting on to thin air a nude woman. “I think I wanted to express several feelings through it. Body image issues, for instance, and also that women are creators of their own identities,” says Reya. She adds, “I like people reading and interpreting my work in their own ways. I just hope the softness and vulnerability that I try to express through my art shines through.”