While marvelling at the arched, ornate, stone columns near the sanctum sanctorum of the Ekambareswarar Temple in Kanchipuram, I muttered a silent prayer for a Russian bloke. The prayer wasn’t for Vladimir Putin — shrines are not meant for profanities — but for Alexis Soltykoff, a blue-blooded traveller and artist, who had visited Kanchipuram in the nineteenth century. The Russian had been put in a trance by, what he writes is, the magic and the music of Kanchipuram’s temples.

Walking on the cool, polished stones of the Ekambareswarar Temple, or on the baking surface of the Kailasanathar shrine — reminders of the magnificent aesthetics and engineering of Chola and Pallava kings — I realised the spell is yet to be broken. The music lingers too.

I was joined by a devotee at another smaller Shiva shrine, his forehead creased with streaks of vibhuti. The man and I stood in silence, separated by the chasm of language. But soon, a bridge, one of melody, began to be built, note by note, as he began humming an utterly bewitching hymn to his lord.

The path to this realm of devotion is often paved with obstacles — primarily the harsh Chennai sun (even in January) and the smog that cloaked the highway that connects Chennai to Kanchipuram. Mercifully, the journey took a little over an hour, the smooth but dusty road arrowing past the emerging rash of industrial hubs on what must have been verdant countryside.

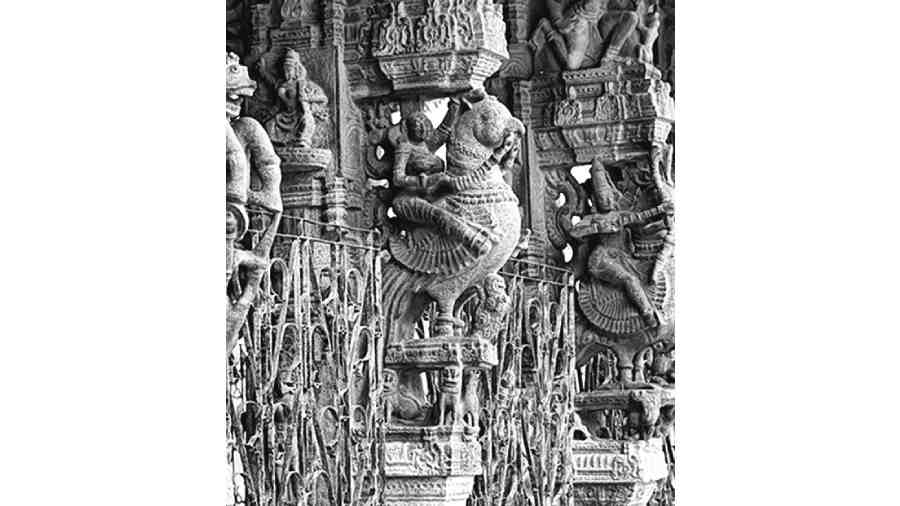

But after taking a sudden turn at a bend, I felt that the debris — the hubris — of industrial modernity had been left behind. The metropolis’s urban sprawl began to cede space to houses, including the spartan dwelling of the former chief minister, C.N. Annadurai, with their typical — wonderful — thatched roofs. The highway gave way to narrow lanes that sprouted kiosks selling sweetmeats, fruits, incense and flowers; each lane seemed to lead, inevitably, to temples, tall or tiny; the peal of bells rung in my ears while I breathed in a peculiar aroma, with scents sacred and profane. What I sensed was another strange intersection — a fine balance between the bustle of pilgrims and the stillness of their destination, those ancient, spellbinding shrines, many of which sported thousands of tiny, intriguing figurines on the gopuram (entrance tower).

Some of Kanchipuram’s sights, sounds and smells can undoubtedly be found in other temple towns of the country. But there is one aspect that sets Kanchipuram apart: a non-hierarchical, democratic arrangement of the places of worship. Unlike, say, Puri, Deogarh or Tiruvannamalai, where one shrine lords over the rest, Kanchipuram casts a magnetic pull on its visitors, drawing them in several directions all at once, a point reiterated with far greater intellectual finesse and depth by Emma Natalya Stein, the author of Constructing Kanchi: City of Infinite Temples.

Interestingly, my sojourns inside the temples — Ekambareswarar, Kailasanathar, Vaikunta Perumal — seemed to crystallise into a richly secular experience. Wandering around the cool, shadowy premises of the Ekambareswarar, the mind puzzled over the dazzling architecture chiselled and hammered into wondrous shape and form with rudimentary tools all those years ago.

Elsewhere, at the Kailasanathar, one stood frozen, in a moment of awe, trying to soak in the brilliance of the frescoes, of gods, warrior men, dancing women and fantastic beasts, on walls that have stood the test of time. A smaller shrine some distance away was, I discovered, a shelter for furtive love in a conservative town, while another one near it had been transformed into an accommodating space for spirited, playful children.

That a communitarian bond, over and above the rituals of divinity, binds the town to its temples had been reiterated, ironically, by Covid-19. As the virus raged through the town and the temple bells and musical instruments — such as the thavil — fell silent, Kanchipuram’s temples came to life in a different way, serving as sites of sustenance by distributing food to the sick and needy.

Were the divine forces merely repaying a debt? For life had been breathed into some of Kanchipuram’s temples suffering from institutional neglect by a collective of ordinary men and women. The Airavatesvara temple, yet another relic from the reign of Pallavas, had been rescued from oblivion by a lawyer based in Chennai and his comrade — a man who sells tea — in Kanchipuram.

I couldn’t visit that shrine. Neither did I meet its saviours. But before returning, as the town’s temples began to be lit up, I did say a little prayer for these two.