In 1970, a comic strip was published in the annual issue of a Bengali children’s magazine called Manihar. The hero of the strip, Bangadesher Ranga, was a fearless Bengali animal trainer living in Brazil. And his name was Suresh Biswas.

“The story was imaginary but the character was based on Biswas,” says Swagata Dutta Burman, who edited a volume of the collected works of illustrator Mayukh Chowdhury, the creator of the comic strip. There is mention of Biswas in one of Satyajit Ray’s Feluda stories too. But who exactly was Colonel Suresh Biswas?

Recently, an 1899 biography of the man was republished by Jadavpur University Press. This book by H. Dutt — titled Lieut. Suresh Biswas: His life and Adventures — and another biography in Bengali by Upendrakrishna Bandyopadhyay published in 1905 were the primary sources of information about Biswas for the longest time.

We know from these that Biswas, born into a Vaishnava middle-class family in Nathpur, Nadia, was an independent spirit and a rebel even when he was a boy. At 14, after an altercation with his father, he left home and converted to Christianity. Soon after, he started looking for a livelihood. The job hunt first took him to Rangoon and then Madras, after which he boarded a ship that sailed for London.

Once in London, Biswas did all kinds of odd jobs to stay afloat — he was a newspaper boy, a pedlar, an acrobat in a circus. It was at a circus company in Kent, a county in South East England, that he learned to be a lion-tamer.

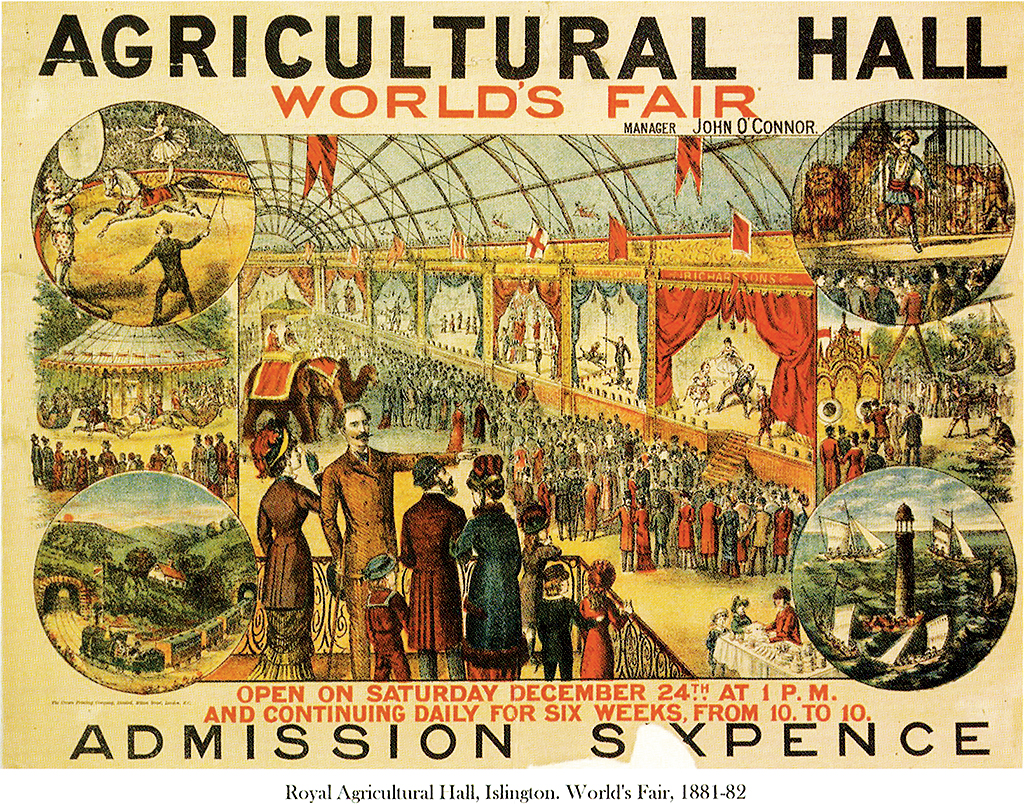

The first independent mention of Biswas’s presence in Europe can be found in the publicity material for the World’s Fair (1881-82). They show him at the cage door with the lions seated behind. He is dressed in boots, red trousers and sash, blue jacket and turban. He also sports a luxuriant moustache. “He was allowed to give an exhibition of his wonderful mastery over the most ferocious and intractable beasts in the World’s Fair held at the Royal Agricultural Hall in London,” writes his biographer Dutt.

When Maria Barrera-Agarwal, attorney, scholar, writer, translator and married to a Calcuttan, read about Ray’s Bengali lion-tamer in Brazil, she was curious. A native Spanish speaker born in Ecuador, she looked up the government archives in Brazil and unearthed a fascinating story.

Biswas had arrived in South America for the first time in 1885, along with a tiger and two lions he had trained while in the employ of famed menagerie owner, Karl Hagenbeck of Hamburg. He had been contracted by The Carlo Brothers’ Equestrian Company and Zoological Marvel to perform with the wild cats and an elephant named Bosco.

A young Biswas debuted with his wild cats to great acclaim in Buenos Aires, Argentina. His success and top billing followed him to Rio de Janeiro in Brazil, where the royal family visited the circus to see his performance.

From Brazil, he went back to Hamburg, only to return in 1886. Some documents Barrera-Agarwal dug up, reveal his age at the time to be 26. The occupation noted against his name in the ship’s papers read “kunstler”, which is German for performing artiste. However, in a letter to his uncle dated spring of 1887, he writes that he has been transferred to St. Cruz, a village near Rio de Janeiro, to look after the horses of his cavalry regiment — indicating that in less than a year’s time he had decided to switch careers. He joined the PMDF, a military corps set up to protect the government of Brazil and the capital city.

Dutt sheds some light on the mystery of the great switch. It seems during a show in Rio, he caught the attention of a doctor’s daughter, Maria Augusta Fernandez. And it was she who gently suggested that she would like to see him in a soldier’s uniform. (In 1951, a member of the Indian consulate in Brazil sought the help of a local newspaper to trace Biswas’s family. He met with his wife, Maria Augusta, who spoke of her late husband very fondly.)

Corporal Biswas eventually rose through the ranks. It seems he showed such exceptional courage at the battle of Nitheroy, an 1893 naval uprising, that thereafter he was made first lieutenant.

Though in Indian lore Biswas is often referred to as colonel, Barrera-Agarwal points out that he never became one. When Biswas died in 1905 at the age of 47, he was captain.

Biswas continued to write letters to his uncle Kailash Chander all his life. In one of them he writes, “I will soon go away from here and invent something that will enable me to travel, because, by travelling only I am happy, for, this gives the idea and nourishes it, of reaching home some day…”

But home he never managed to return to. Perhaps he didn’t try hard enough, though it was on his mind all through as we gather from his letters. His iteration about how he, a vagabond, had done well, his pointed queries about his father who had disinherited him when he was barely out of his teens, and his wish to see his mother again.

In the Introduction to the 2018 republished version of Dutt’s biography of Biswas, Barrera-Agarwal writes: “The need of a hero is indispensable in human society.”

In the last available letter to his uncle, Biswas writes, “I have had several letters addressed to me by many young men of Calcutta, asking me if there is no means of coming here in Brazil. I shall answer them separately.”

First record of his performance in Europe, at the 1881 World’s Fair (top right circle) Image: The Telegraph File