Etymology

Bhaang is derived from the Sanskrit bhanga. Nineteenth-century British scholar of Kama Sutra fame, Richard Burton, points out that the Arab banj and Hindu bhaang derive from the old Coptic nibanj, meaning a preparation of hemp. The Persian equivalent is bang. The Portuguese translated it as bangue.

References

The earliest usage of the word bhaang is in the Atharva Veda (1400 BC). Sanskrit grammarian Panini uses it in the sense of the pollen of the hemp flower; he calls it bhangakuta. It is first mentioned for its medicinal “anti-phlegmatic properties” in the Sushruta Samhita. That would be 6th century BC, while later researchers note that bhaang was also extolled for pain-relieving properties and even later, for “problems of appetite and digestion, gastrointestinal illnesses, rheumatic troubles, dysuria, gonorrhoea”. The next many centuries, in Sanskrit dictionaries, bhaang is used as a synonym for a hemp plant. Cakrapanidatta, who was a physician in the court of Nayapala in the 11th century, used the name “Indracana” for bhaang, meaning, food of Indra. By the 16th century AD, references to bhaang are to be found in popular literature. In the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission (IHDC) Report from 1894-95, G.A. Grierson, who was magistrate and collector of Howrah, notes: “Bhaang is frequently mentioned by vernacular poets. The oldest instance with which I am acquainted is the well-known hymn by Vidyapati Thakur (1400 AD), in which he calls Shiva ‘Digambara bhanga’.” In the Zend-Avesta too, there is a reference to bhaang, as Zoroaster’s “good narcotic”, but bhaang is possibly more famous here as Shiva’s drink.

Usage

In The Materia Medica Of The Hindus (1900), Uday Chand Dutt makes the distinction between ganja, charas and bhaang. Under the chapter headed “Cannabis Sativa, Linn. Var. Indica”, he writes: “Ganja, the dried flowering tops of the female plant, from which the resin has not been removed. Charas, the resi- nous exudation from the leaves, stems and flowers. Bhaang, the larger leaves and seed vessels without the stalks.” In one of his research papers, Utathya Chattopadhyaya, who is an assistant professor in the department of history, University of California, Santa Barbara, US, puts it succinctly: “Depending on context and usage, it (bhaang) could refer to either a loose dusty cannabis commodity, or solely the cannabis leaves, or the entire cannabis plant, or a set of confectionery drinks made primarily of milk and boiled cannabis leaf that were differentiated by culinary combinations of nuts, spices, and cream.”

Constituency

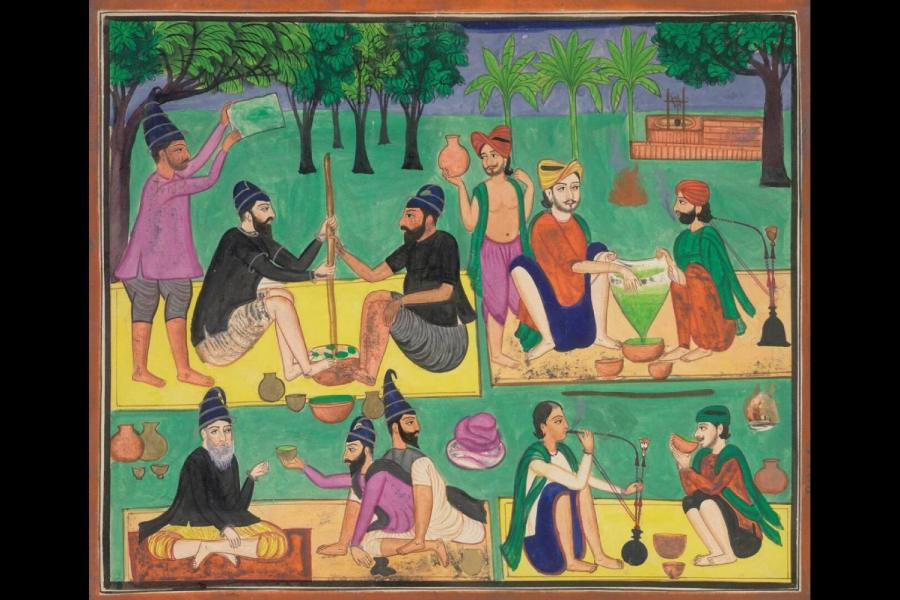

So who consumed bhaang? According to Dutt’s book, which claims to be not a literal translation of any treatise, bhaang was popular among all classes in 19th-century India, especially in the North-West Provinces and Bihar. In the context of Bengal and the Bengali, he observes that on the last of Durga Puja, following the ritual immersion of the idols, “it is incumbent on the owner of the house to offer to his visitors a cup of bhaang and sweet-meats for tiffin”. Dutt, however, says that the “intoxicating agent” has been replaced by brandy in some homes in Bengal, whereas during his boyhood more of the “better classes” partook of it. Bhaang enjoyed currency among Vaishanavas as well as Shaivas. Grierson says bhaang consumption is not considered “disreputable among Rajputs” he cites a poem by Ajabes, court poet to Maharaja Bishwanath Singh of Riwa, by way of proof. “He wrote a poem praising bhaang and comparing siddhi to the ‘success’ which attends the worshipper of ‘Hari.’... The word siddhi means literally ‘success’, and hari means not only the god Hari, but also bhaang.” In his piece on the religion of hemp in the Indian Hemp Drugs Commission Report, 1894, J.M. Campbell, collector of land revenue, customs and opium, wrote: “...the North Indian Mussalman joins hymning the praises of bhaang... It is the spirit of the great prophet Khizr or Elijah... From its quickening the imagination, Mussalman poets honour bhaang with the title Warak al Khiyall, Fancy’s Leaf.”

Properties

James Mills, who is director of humanities research at the University of Strathclyde in the UK with several books on cannabis such as Cannabis Britannica: Empire, Trade and Prohibition 1800-1928 and Cannabis Nation: Control and Consumption in Britain 1928-2008, draws attention to the Taleef Shereef translated by George Playfair, superintending surgeon, Bengal service, in 1833. The book published by the Medical and Physical Society of Calcutta is really a long alphabetical list of “native medicines”. It begins with am, includes ghafis, kakolie, lahsun, mogra and ends with hingool. Here is a portion of the entry against bhaang. “Cannabis Sativa, a name for Kainib, called also Bidjia; it is pungent, bitter, hot, light, and astringent; it promotes appetite, cures disorders of phlegm, produces idiotism.” Playfair puts down a recipe of Bidjia, sugar, honey and ghee. He writes: “First fry the Bidjia in the ghee, then add the honey in a boiling state, afterwards the sugar: use this in moderate doses daily, and when it has been used for two months, strength and intelligence will have become increased, and every propensity of youth restored; the eye-sight cleared, and all eruptions of the skin removed...”

Tragic potion

“In the 1857 rebellion, many English reporters and newspapers justified the imperial violence against the rebels using the logic that bhaang was inside the rebel’s body and thus the main reason for their ‘irrational violence’,” Chattopadhyaya tells The Telegraph. He has written a paper titled A Primer for Rebellion: Indian Cannabis and Imperial Culture in the Nineteenth Century, wherein, among other things, he examines the role of “military dispatch” by reporters and British soldiers during the rebellion of 1857-59 in creating a certain narrative about Indian cannabis. So, from being something consumed by the ethnographer’s “old favourite servant” pre-1857, bhaang becomes this villainous substance in internal reports by British officers. Chattopadhyaya cites a Major General Hearsey as saying that other soldiers did not stop “Mungul Pandy from behaving in a murderous manner” as he had taken too much bhaang.

In moderate doses

In 1893, when a question was raised in the British House of Commons concerning the effects of the production and consumption of hemp drugs in Bengal, the Government of India set up a seven- member commission to look into them. The objections, by some accounts, were raised by missionaries and possibly had to do with the “disapproval of indigenous religious practices which involved consumption of cannabis”. Thereafter, the investigation included all of India and the result was the IHDC report of 1894-95 comprising seven volumes and 3,281 pages.

But surprise, surprise, the commission did not ban the use of cannabis. Reason proffered: it was considered neither “necessary nor expedient”. Writes Chattopadhyaya in his paper Reading Cannabis in the Colony: Law, Nomenclature, and Proverbial Knowledge in British India: “The British government in India, struggling through financial crisis, anxious over raising taxes, worried about the backlash from the Royal Commission on Opium, and blamed for emerging tensions between Hindus and Muslims following the rise of the cow protection movement in the previous decade, could simply not afford to interfere in any drastic way with Indian social life.” The IHDC let it be known that it had been established that the “occasional use of hemp in moderate doses may be beneficial”.

A wink and a prayer

The NDPS Act of 1985, which is the law related to narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances in India, covers charas and ganja but is coy about bhaang.

It excludes “the seeds and leaves when not accompanied by the tops”. And so, bhaang continues to be cultivated legally. And it continues to lend flavour to our festivities.

After all, at any cost, the gods have to be happy.