I had a registered marriage. That wasn’t unexpected — I had declared I would never take seven rounds around a fire ever since I was old enough to understand, and object to, the mantras used. But the exact time when I signed the certificate was decided by the panjika.

My father wanted an auspicious moment though he did not approve of either the wedding or the groom. My aunt who was overseeing the ceremonial details was worried how we’d find the right time, as any almanac consulting my mother’s side of the family ever did was via priests. Maasi was embarrassed to consult the family priest for a shubh muhurt and then say he would not be needed at the appointed hour.

She need not have worried; my father’s family was much more hands-on when it came to consulting almanacs. In fact, buying a panjika was an essential part of our Poila Baisakh, along with new clothes, sweets and mutton for lunch.

The panjika was and is a fascinating book, bulky with a flimsy cover and chock-full of such arcane information as to which vegetables to avoid during which months (radish in Magh) and what time is unsuitable for celebrations (Bhadra and Chaitra). It tells you what time you should set out for a journey and what time you should not. There was a huge hullabaloo at a cousin’s wedding because the panjika said post 2pm the day after her wedding any kind of journeying was not to be undertaken; in its own words — jatra nasti. The easy solution was to hold the bidai in the morning except that it went against all the traditions of my conservative family where brides are never sent off before noon. After much debate, my cousin left at noon, seen off with a fervent chanting of shlokas that were supposed to protect her from bad times. She left behind weeping parents and a bunch of us, non-believers, in splits.

My mother consulted the panjika before fixing a bhalo date and time when I would give birth to my son by Caesarean section. The doctor simply said it was common practice and did not understand why I was livid.

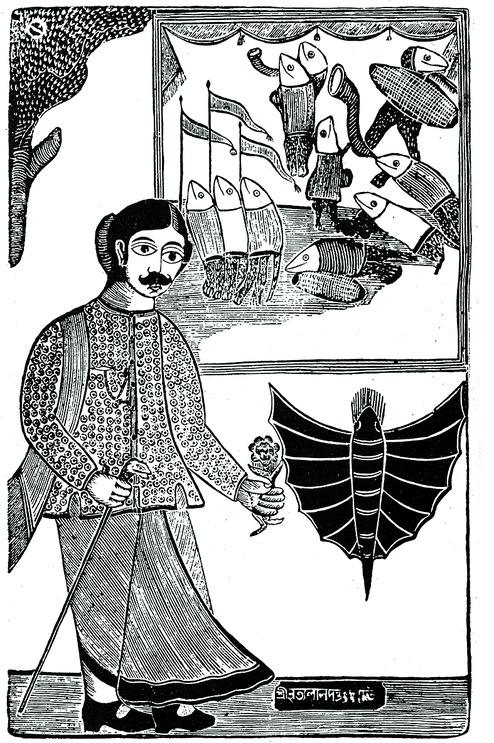

While I loved leafing through the panjika as a child, it was only much later that I learned to decipher it. To be honest, I thought those cryptic sets of numbers boring; what I liked were the sketches and the write-ups. I learnt random things from it. For instance, I learnt that different families observe different mourning periods — 11 days, 13 days and 15 days.

For the longest possible time, I thought all panjikas were the same, until my busy father asked me to pick up a copy one year and I came home with the wrong one. Turned out, I had never taken the trouble of finding out which panjika my family consulted. I knew for sure that the family did not follow Bisuddha Siddhanta because I had often overheard the grandparents disparaging its weird timings for puja — this is when Durga Pujas were being condensed into two and three days.

So when the shopkeeper asked which panjika I wanted, I replied, “The most popular one.” Sure enough he handed me the pink-covered Benimadhab Sil’s Panjika.

I discovered that day that the panjika my father — and therefore I — swore by also had a caste connect. The panjika I had grown up seeing lying around the house was published by Gupta Press, the proprietors belonged to the same caste as my parents. I would have said me except that after an inter-caste marriage, I am not very clear what caste I will be assigned by the keepers of my faith.