In all likelihood, it was love at first sight for Parameswaran Thankappan Nair (1933-2024) when he arrived in Calcutta, a penniless young man on September 22, 1955. But years later, he was disenchanted with the city which was his home till his final departure in June 2018. Nair died at his home in Chendamangalam in Ernakulam district, Kerala, last Tuesday.

Decades later, Nair clearly remembered the morning of his arrival. That was a Thursday. The selection of the site of Durgapur was announced that day. Pather Panchali was still showing in a hall and Ganesh Vivah, starring Nirupa Roy, was released

the next day.

His train — Madras Mail — arrived on time, but from the very next day, all trains had to be diverted owing to floods in Odisha. He waited for three hours till he was rescued by a passing Malayali.

“Calcutta was one of the finest cities then. The hydrants worked and the roads in Chowringhee and Bhowanipore, where I lived, were washed every morning. Dalhousie Square was a beautiful garden. The water of the tank was crystal clear. The refugee problem was there, but they could not be seen in central Calcutta. They crowded Sealdah, Southern Avenue and Ganguly Bagan,” he reminisced.

Being only matriculate (later he became a bachelor of arts and a non-practising lawyer), he started working as a stenotypist in a Dalhousie Square office on October 1, 1955. During lunch breaks, he would take tram rides to familiarise himself with Calcutta.

“If there was an interesting office or old building, I would make a note of it. So many plaques attached to buildings have disappeared,” he used to say.

But now, he had exclaimed in an interview in 2005, “Calcutta is one of the dirtiest cities in India?”

He did not believe all old buildings should be preserved. He was pro-development. Without hesitation, he said, “All heritage buildings must be preserved and strengthened. Other buildings that have no heritage status can be demolished.” With a rider though. He added, “Beautiful buildings should be preserved. If the owner can’t preserve it, the government or the corporation should come forward to preserve it. Old buildings can never be built again.”

It is true that Radharaman Mitra (1897-1992) of Kalikata Darpan fame had explored Calcutta on foot, but long before the word urban historian gained currency, Nair had made many who live in this relatively young city aware of its legacy and its tumultuous past.

Nair had his detractors. Some said he was an archivist, as opposed to a historian. Others faulted him on his ignorance of Bengali. He undeniably had his faults, yet in the 2015 book Calcutta: The Stormy Decades, edited by Tanika Sarkar and Sekhar Ban-

dyopadhyay, the latter wrote “...Calcutta owes a great deal to its resident Malayali scholar, P. Thankappan Nair, whose wide-ranging scholarship explored practically every aspect of the history of this metropolis, from the 17th century to the 19th century — touching on the origin of its name, history of its streets, the beginning of its press, the story of its High Court and its police system, and its more modern south Indian diaspora.”

Slight, dark and unkempt, Nair never forgot the shabby treatment meted out by Jyoti Basu when he presented the then chief minister a copy of his book on the Calcutta Municipal Corporation.

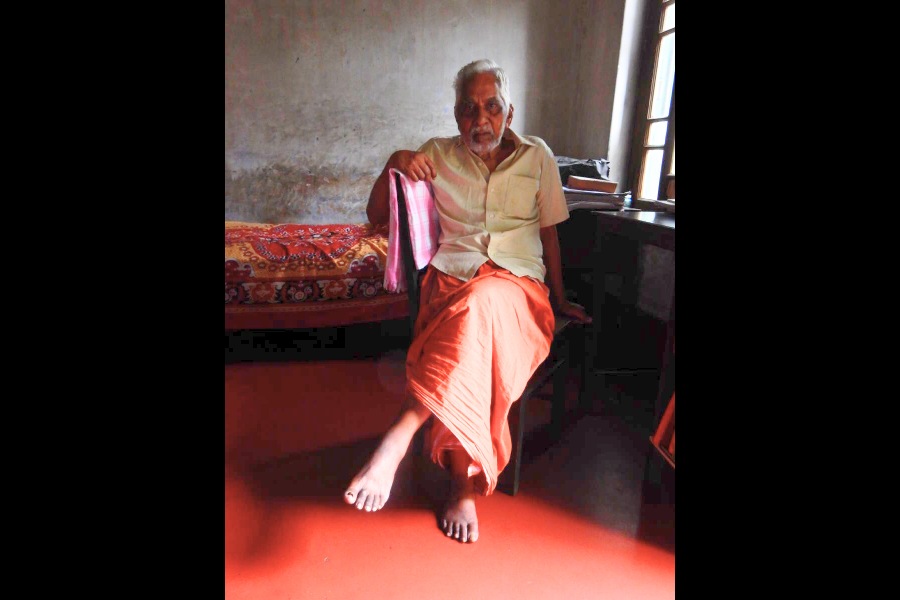

While most people used to see him in the National Library reading room poring over books, journals and maps almost everyday and stumbling upon priceless details better qualified researchers may have missed, I used to meet him on my assignments at his spartan two-room home at Kansaripara in Bhowanipore. The rooms had red oxide floors — the house was old. And while one room was a wilderness of the 3,000 publications, including books, journals, maps and documents Nair had collected over the years, a battered typewriter — on which he had dashed off the 62 books he wrote, besides numberless articles — was the most outstanding object of the second. Many of his books are now out of print but his much sought after A History of Calcutta’s Streets is available in a new edition.

Included in his prodigious collection were old Calcutta directories. “When particular buildings were constructed directories gave their history,” Nair had said. He also possessed a complete set of Bengal Past and Present from 1907 up to present times. The books are preserved in the Town Hall library.

Quite in keeping with his famous frugal lifestyle, Nair survived practically on a single meal every day with perhaps a snack at the National Library canteen. A 10-minute walk took him to the library soon after it opened, and he would spend most of his time there. He used to make annual trips home but he rarely spoke about his family in Kerala. It was only in the years before his departure that I met his mild-mannered wife, Seetha Devi, a retired school teacher. She would offer refreshments.

Calling himself an archival historian, he would declare, “Let the documents speak.” In the early 1970s, he found to his dismay that little research work had been done on Calcutta. “Whatever was written was only guidebooks except for (H.E.) Busteed’s Echoes from Old Calcutta. Academics said no material was available. I said this was nonsense.”

He had culled documents on Calcutta from different catalogues of archives all over the world. Friends helped. For his book, James Prinsep: Life and Work, the will of this multifaceted talent was sought from India Office in London.

“If you can locate your source you can get it,” stressed Nair. The documents on Job Charnock were found at Fort St George in Madras.

When he left, P.T. Nair’s head was full of ideas. But age got the better of him.