A higher secondary school near Manjeri in Kerala was trying to get into the Guinness Book of World Records in 2017 by creating a giant fountain pen from thousands of discarded plastic ball-point pens. Three years later, Sulekha Ink, one of the pioneering ink manufacturers in India, revved up its production. Are the two things connected? Yes, in a manner. Both had to do with the resurrection of the fountain pen.

Around this time the market for ink and the fountain pen was slowly opening up in India as well as abroad. Taking cue, the owner of Sulekha Ink, Kaushik Maitra, revived production after almost two decades, albeit on a small scale.

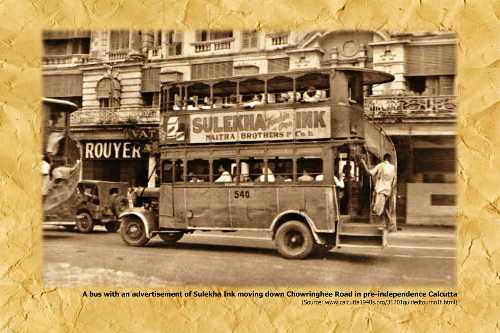

The company was born in Bangladesh’s Rajshahi district. Maitra’s mother and two aunts had started to make ink at home in 1934. Says Maitra, “My father Nonigopal and his brother Sankaracharya would go door to door selling the homemade ink. Soon they realised that the market for ink was robust in Calcutta and they shifted here. By 1945, the business had boomed and my father bought land for a factory in Jadavpur in south Calcutta.”

Sulekha launched three varieties of ink this May. Swadesh, Swadhin and Samarpan were so named apparently keeping in mind historical associations. Maitra says, “We started our business in response to Gandhi’s Swadeshi Andolan.” According to him, a fourth variety named Gorber 50, is meant to celebrate the golden jubilee of Bangladesh’s Liberation War.

It seems within months of the launch, sales soared from 50 bottles per month to 5,000. And the bulk of the order is from Bangladesh.

Amain Babu, who is a historian and journalist based in Dhaka, explains, “We never had any fountain pen manufacturers in our country, but 2017 onwards affordable Chinese pens started coming into the market. The requirement for ink increased.”

Fountain pens and ink had never gone out of use in the Indian market. Subashish Bhattacharjee, a college teacher based in Siliguri, is a collector of fountain pens. He has over 200 fountain pens, and at least 300 bottles of ink in different colours meant for a variety of purposes — writing, sheening, shading, shimmering, permanence and so on.

Bhattacharjee was part of the core group that designed and executed the first limited edition fountain pen designed and made in India in 2019. “The pen was made in collaboration with Lotus Pens and Kanpur Writers, two Indian companies that manufacture fountain pens. A special ink made by Krishna Inks was used,” he says. Krishna Ink was launched in 2010 by Dr Sreekumar who is based in Kerala. Krishna Ink comes in more than 50 colours. These can be used for shading and signing important documents.

Courtesy, Sulekha Ink

The demand for ink has increased also because it is being used increasingly for calligraphy. Dharmendra Bhatia of Daytone Ink, based out of Delhi, produces ink that can be used for calligraphy alone.

According to Bhattacharjee, these days fountain pens are primarily used by people who are not in the business of writing. For such users, the fountain pen is a therapy more than just an instrument. “The process of cleaning out such pens, taking regular care of them, choosing the right ink and paper, and finally putting nib to page to scribble and doodle can be a meditative exercise. Users experience a sense of peace.”

Pen collector Vedisha Singhi, who lives in Mumbai, has a name for it — graphotherapy. She also believes that those who write with a fountain pen tend to express themselves better.

There is also a school of thought that advocates the theory that a fountain pen gives away a person’s identity and personality. How so? Says Vedisha, “It is just that the iridium nibs are known to wear away at different angles for different people.”