What does a war crime look like?

It looks like the lacer- ated buttocks of Israa Abdul Karim. She was five years old in the Al-Mansour Hospital for Children in Baghdad when I saw her that April of 2003.

She was on her stomach. Tears dried on her cheeks. Every time she retched the saline bottle shook. Her mother, Karina Ali, 35, sat between her and her brother, Saif, 7, hands bandaged, on the same bed.

The Al-Mansour Hospital was known as the Saddam Hospital days earlier. The Ameri-cans had bombed their way in. The regime was changing. Saddam Hussein’s statue in Al Firdaus Square in front of the Hotel Palestine, in the overcrowded lobby of which I was camping, was pulled down.

The hospital had 500 beds. There were only two doctors. It was full. Between them, they could see only 60 children. Israa was Dr Abdul Hamid al-Sadoun’s patient. He dragged me by the hand. “Come here, come with me and take a look. Okay, you don’t want to meet all the patients? But we have to live with them. You are a sahafi, a journalist, and you can’t bear to look at them.”

Israa’s family was fleeing their village near Abu Ghraib, 40 kilometres from Baghdad, two nights earlier. Abu Ghraib hit the headlines the following year after photographs of naked prisoners, tortured by dancing and drunk American soldiers and piled on top of one another, leaked.

What does a war crime look like? It looks like the haggard face of Mohammad Ibrahim Rahim Baksh, then 76. He spoke a smattering of Urdu.

His father had migrated to Baghdad from Karachi in 1914, the year of World War I.

In House No. 5, Mohalla 604, Zokak 14 in Baghdad’s Qadisiyah, the family of 24 used to sit down to dinner. Grandfather, grandmother, widowed daughters-in-law and grandchildren. Their fathers were Faroukh, Faisal and Fareed.

Faroukh was shot in the Iraq-Iran war of the 1980s. Faisal was also killed in that war, probably gassed because his body had no visible wound.

The family had just got news that Fareed, also a soldier, was wounded and dying in Al Amara. They had no means to travel.

Dinner was khabbus, a lamb soup, and batinjon, a gruel of tomatoes and potatoes. Fish for the family cost 7,000 Iraqi dinars, two chickens 4,000 ($1 then meant 3,000 dinars).

“We stocked up for the war like everyone,” said Fariyal, one of Baksh’s daughters.

“We stored food and water because we knew our locality Qadisiyah will be bombed but we had nowhere to go. There is a Ba’ath Party office here. Along the river (the Tigris), every house is in ruins.”

Qadisiyah was predominantly Sunni Muslim, supporters of Saddam Hussein.

“Even a week back we saw him over that bridge (on the Tigris) waving, and we thought there is going to be a real battle but nothing happened and suddenly the Americans were at our door,” recalled Baksh.

Around Baghdad, anti-aircraft guns were on rooftops. Abandoned. Ditches and tren-ches were empty. Saddam’s generals or the vaunted Republican Guard had melted or, as my host suspected, bribed.

What does a war crime look like? It looks like Safwan, Iraq’s first village on the border with Kuwait in the south.

The American war machine rolled through Safwan the night of “shock and awe” — the war broke with the bombing of Baghdad, an attempted “decapitation” of the Iraqi leadership. Safwan was incinerated, the first time US forces were known to have used such bombs since Vietnam.

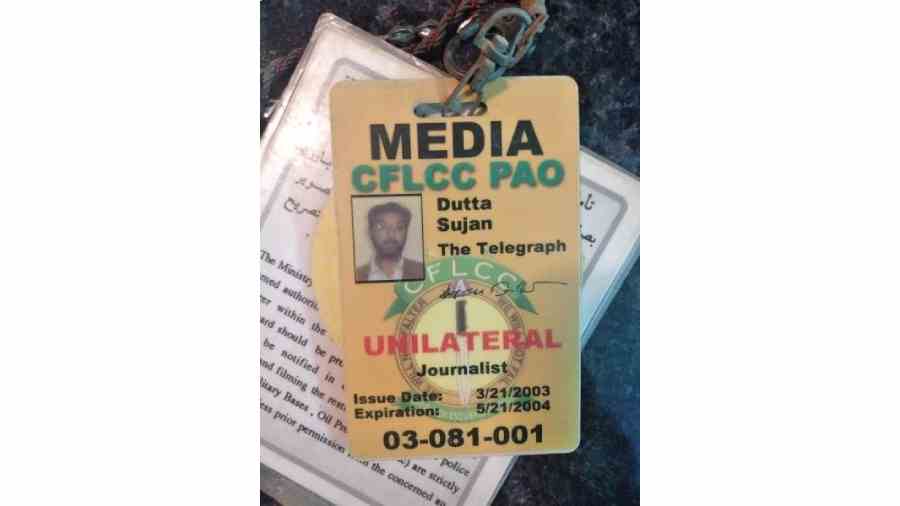

Dutta’s Press ID issued by the Pentagon during the Iraq invasion. ‘Unilateral’ meant he wasn’t embedded with the invading forces

An Indian army officer, Brigadier Upinder Clair, was the sector commander of the United Nations Iraq Kuwait Observer Mission. Through rough sketches in my notebook, he described the lay of the land. The UN sector headquarters was now a command post of US and British soldiers.

Safwan was across a sand berm. To the left and right in the desert, I saw surface-to-air missile launchers, Patriot defence systems, aimed skywards to shoot down Iraqi Scud missiles.

The Americans had used a WMD — weapon of mass destruction — on Safwan. They were looking for fictional WMDs. But the war crimes were real.

I entered Safwan with Red Crescent volunteers in a convoy of trucks carrying relief.

As the convoy entered the village, a riot broke out. The villagers had gone hungry for days. We were being looted. A correspondent with the Spanish newspaper El Pais fell down. The mob attempted to grab her cameras till I managed to pull her out with help from an American sergeant who was firing in the air and shouting “WE HAVE A SITUATION HERE” into his radio mouthpiece.

Despite sanctions, Iraq always had a public distribution system. Bread was almost free in community bakeries. Since the war machine rolled, the people were mad with hunger.

In Umm Qasr, Iraq’s port in the Persian Gulf, I was saved from within a mob of port workers by some of them who asked if I was Kuwaiti and when I said “Al Hind” (Indian), I was spirited away to safety.

What does a war crime look like? It looks like a roaring well in the Southern Rumailah oilfields and an M1A1 tank amid shards of porcelain and pottery. It looks like miles of garbled microfilm and tattered Sanskrit, Arabic, Persian manuscripts in the Baghdad National Library. A war crime is a neat hole drilled by a “smart bomb” on the brown gate of the Baghdad National Museum, the cradle of civilisation.

A war crime looks like an Alibaba. “Alibaba” was the name given to rioters and looters who ran amok in Baghdad, plundering the museum and the library and public property in the days before the Americans dominated.

Baghdad was smouldering when I entered the city, driving a thousand miles from Amman in Jordan through the cold desert night.

In the early hours, there were columns of thick black smoke between brown Earth and blue sky. The office block by the television tower was smart-bombed. The ministry of trade was smart-bombed. The six-storey block of the Iraq International Olympic Association, then headed by one of Saddam’s sons, was charred.

I headed first to the museum. Opposite it, in a government office, Alibabas were taking away furniture. In the campus of the museum was an American M1A1 Abrams tank, its barrel over my head.

I had read about the looting of the museum on the mobile phone by a column of belching fire and smoke from a wellhead in the Southern Rumailah oilfields. A Kuwaiti mobile network was accessible.

“Our feet crunched on the wreckage of 5,000-year-old marble plinths and stone statuary and pots that had endured every siege of Baghdad, every invasion of Iraq throughout history, only to be destroyed when America came to ‘liberate’ the city,” the late Robert Fisk reported for London’s The Independent.

I personally witnessed the looting of the Baghdad National Library, holding up in des-pair the films and the charred manuscripts, taking what pictures I could in a hurry.

Twenty years ago this season, I thought I was reporting a war for The Telegraph.

I was really reporting a series of war crimes.