The talk was on at Calcutta’s Victoria Memorial Hall. Author, critic, publisher Samik Bandyopadhyay, who was the main speaker, was saying, “I was visiting theatre director Ratan Thiyam in Imphal... A few years before that, Sangeet Natak Akademi had awarded their annual best theatre director award to Ratan Thiyam and the best Manipuri dancer award to his father Tarun Kumar on the same stage. Ratan took me to his house and introduced me to his father. Tarun Kumar gave me his scrapbook and went inside to make tea for me. I opened the scrapbook. The first page was empty, except for one news item, ‘Haren Ghosh killed in riot, his dismembered body found in a suitcase in Rawdon Square’ with a caption that read ‘Independence’. The next page had another news clipping on Ghosh’s Bengal Music Conference, wherein Faiyaz Khan sang followed by a dance recital by Tarun Kumar and his wife Bilasini Devi.”

Haren Ghosh died in 1947, but first, who is he? In The Oxford Companion to Music, Ghosh is identified as an impresario, a word that does not mean much in these parts. It traces its origins to mid-18th century Italian opera and is a descriptor for the key organiser of an opera. The owner of a theatre would hire an impresario, who would proceed to find a composer, an orchestra, singers, costumes, sets, all of it. In Europe and America, impresarios such as Sergei Pavlovich Diaghilev, Vaslav Nijinsky, Anna Pavlova and Sol Hurok are venerated even now. It was after Diaghilev that Ghosh sought to fashion himself.

Ghosh was born on December 8, 1895, in Sripur village in undivided Bengal’s Jessore district. After a few years at the village school, he joined Hare School in Calcutta. He went on to study automobile engineering abroad and film-making too. Upon return, he started a business in automobiles but his metier lay in the arts.

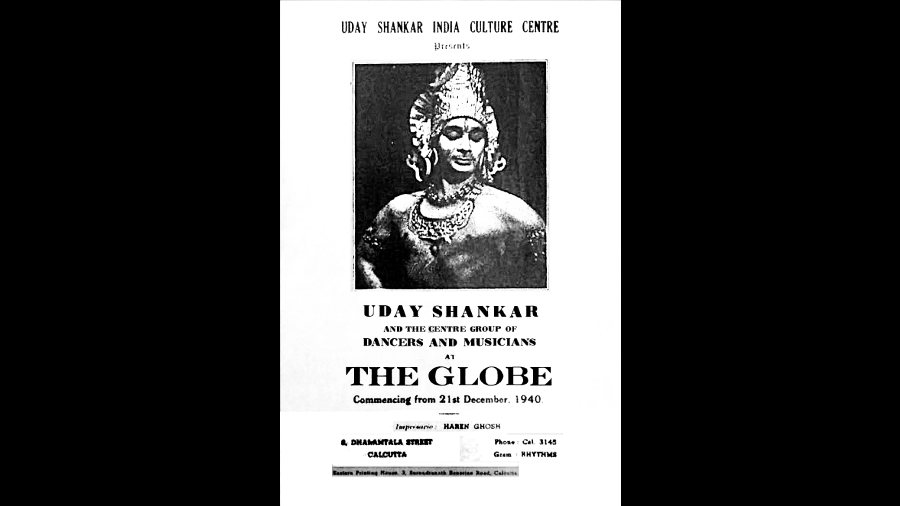

He gifted Calcutta the Cinema Library on Dharmatala Street. He founded Arya Films, which made movies such as Buker Bojha, Aparadhi and Sainik. He got Raichand Boral and Pankaj Mullick to compose music for the film Chorkanta. Ghosh also started the Four Arts Annual, a one-of-its-kind journal with in-depth write-ups on dance. But his most legendary effort was — presenting to the world the genius of Uday Shankar.

Uday Shankar had been to London’s Royal College of Arts. As part of Anna Pavlova’s troupe, he did two 10-minute programmes on Hindu marriage and Radha Krishna. He did several performances with Pavlova. And yet, when he returned to India in 1921, he was still a nobody.

A poster of Uday Shankar’s performance arranged by Ghosh.

But Ghosh had read about Uday Shankar and decided to promote him. The story, as narrated by Gautam Bagchi in his recently released book Adwitiyo Impresario Haren Ghosh goes that Ghosh first took him to the writer Hemendra Kumar Roy, who advised them to consult Abanindranath Tagore. Ghosh organised a programme and invited the who’s who of Calcutta. Among the guests were music composer Timir Baran Bhattacharya, Abanindranath himself, art connoisseur Ordhendra Coomar Ganguly and others.

The programme mesmerised all. Uday Shankar and Timir Baran became friends and formed a group that started putting up performances. Before their Europe tour, Ghosh organised some pre-departure programmes at the New Empire Theatre. Even Rabindranath Tagore came to New Empire. The group’s next stop was Paris and, thereafter, England and the US.

Ghosh also organised tours and concerts that spread the renown of Bala Saraswati. Satyajit Ray, who made a documentary on her, wrote in Sangeet Natak, the Akademi’s quarterly journal: “Since we trusted Harenda’s judgement, we all went to see Bala Saraswati. A tall girl, with long limbs and a round face, doing a kind of dance I had never seen before at the Senate Hall…”

Ghosh was planning to establish a national theatre workshop and was in talks with Jawaharlal Nehru about it. The year was 1947. There had been terrible rioting in Calcutta all through June and July. On July 9, Ghosh left for his office on Dharmatala Street. It was near the epicentre of the deadly riots. At around 6pm, a suitcase containing his dismembered body was found in Rawdon Street near the Park Street Police Station.

Bandyopadhyay had asked Tarun Kumar why the first page of his scrapbook had that single item about Ghosh’s death. Tarunbabu told him, “It’s all because of him. He had taken me to so many places. When the riots started, all programmes got cancelled. I went to Nabadwip. There I received a letter from him at the beginning of July. ‘Riots have stopped,’ he wrote, and asked me to come to Calcutta. I was at Nabadwip station. The train to Calcutta was late. I bought a newspaper and read the news. Everything came to an end for me.”