“I tumbled off my horse, and dashed half-fainting into Peliti’s for a glass of cherry brandy. There two or three couples were gathered around coffee tables discussing the gossip of the day.” So wrote Rudyard Kipling in the short story titled The Phantom Rickshaw. Kipling was referring to Peliti’s in Shimla, but here in Calcutta too there once thrived a Peliti’s.

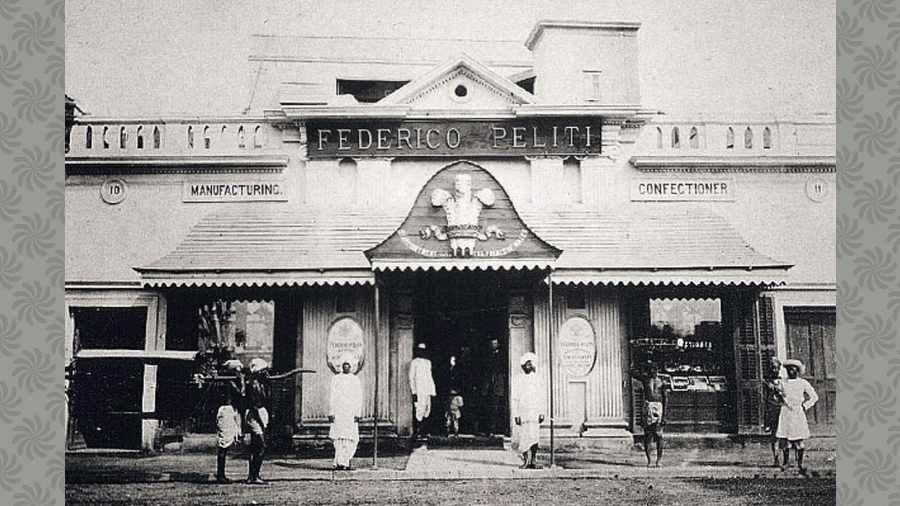

Peliti’s of Calcutta started out in the 1870s as a confectionery outlet on Bentinck Street and thereafter turned into a fine dining restaurant-cum-confectioner’s on Esplanade Row. “Business ended with World War II,” says Maria Letizia, who is a great-granddaughter of the founder, Federico Peliti, and is now based in Turin in Italy.

In 2021, during his first official visit to the city, the Italian ambassador to India, Vincenzo de Luca, spoke about reviving the place. He said the restoration could be a “good starting point for Bengal-Italy cooperation in the heritage regeneration of the city, which should assume a movement involving stakeholders from different institutions as it happened in the heritage movement in cities like Bologna and Naples”.

Peliti’s now Pradip Sanyal

Speaking of starting points, Peliti’s indeed played a key role in defining the flavours and cultures that have come to define Calcutta.

Says Maria, “Federico was largely responsible for popularising Western-style confectionery and ice cream in India.”

Federico, who was from Piedmont in northern Italy, had trained as a sculptor to begin with. He graduated from the Accademia di Belle Arti. So, when he turned to the business of food after serving in the Third War of Italian Independence as a cavalryman, he brought to it his sculptor’s sensibility. “He was famous for neo-Gothic monumental cakes,” adds Maria. It seems an image of Queen Victoria in cake-icing chocolate was made for the Queen’s jubilee celebrations. And in December of 1889, he prepared a 12-inch replica of the Eiffel Tower in sugar. Before he opened shop in Calcutta, Federico held the post of master chef of the Viceroy of India, Richard Southwell Bourke, till the latter’s assassination.

A marble plaque that survives Bishwarup Dutta

Firpo’s, the other culinary landmark of the city, was set up by Angelo Firpo of Genoa, also in Italy; Angelo had worked at Peliti’s in Calcutta earlier.

The restaurant menu included typical Italian dishes such as risotto alla Milanese, agnolotti, maccheroni, ice cream and also the British mince pies and French filet de boeuf. Maria emails an image of the dinner menu of St. Patrick’s Day, 1911. Some of the items on it are: canapes varie, consomme royale, filet che boeuf, poularde a la moerne and so on. A three-course luncheon cost Rs 1.50, and it remained unchanged between 1917 and 1924. Federico also started a catering service, taking orders “from all over British India, including Burma”.

And then, of course, there was his famed vermouth.

An old advertisement File photo

In A Taste of Time: A Food History of Calcutta, Mohona Kanjilal writes about the white vermouth Federico made with Indian spices for Prince of Wales Albert Edward, when he came visiting in 1875. The prince liked it and, Kanjilal writes, “Since 1877, this original recipe went into production, especially to be supplied to the English Royal House at the request of the prince.”

Federico also opened a factory back home in Carignano in Italy, where he produced canned fruits and vegetables that made their way to his restaurants in Calcutta and Shimla. He also set up a distillery to produce vermouth.

And then, at the turn of the century, he handed over the business to two of his sons and left for Italy.

Today, the only reminder of the place is a marble plaque at 11 Government Place East with an inscription beginning, “By Special Appointment, To His Excellency the Viceroy, Federico Peliti, importer of English, French and Italian provisions”.

Beyond the entrance to the building, which is now a property of the Life Insurance Corporation of India, all is dark and dank. Closed and shuttered offices line the ground floor, which was most likely where the confectionery operated from. A naked tubelight illuminates what was once a grand staircase with elaborate wrought iron railings. The first floor with its partially covered balcony must have been the restaurant.

From Allister Macmillan’s Seaports of Indian and Ceylon, we know that once upon a time the tables were covered with spotless linen, the spoons glittered, the decorations were charming and coloured electric lights hung in the form of baskets of fruit and flowers. There was orchestra and dancing too and all of it combined to make a visit to Peliti’s “very pleasurable”. Macmillan writes about the “spacious sections of the upper floor that have made Peliti’s so popular”.

For now, the only occupant of this floor is the Bijoynagar Tea Company established in 1925.

And what has become of the restoration plans? Says Maria, “I was contacted by the Italian Consul about its restoration. But nothing concrete has emerged yet.”