Paris in the early decades of the 20th century had its share of frenetic socialising; one can only imagine the hobnobbing crowd at the different cafes — Henri Matisse, Amedeo Modigliani, Pablo Picasso, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway and countless others. There was a sense of freedom and dealers were looking to invest in young talent.

Matisse and Modigliani — two titans of the 20th century art world — have their respective exhibitions in Philadelphia. Modigliani’s works have been parked at the Barnes Foundation as part of the exhibition ‘Modigliani Up Close (October 16 to January 29, 2023) while those of Matisse (titled ‘Matisse in the 1930s’, October 19 to January 29, 2023) are up at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Matisse lived a long and abundant life as an artist (1869-1954) while Modigliani (1884–1920) met a premature death only after which his genius was recognised, becoming a central figure of Modern Art.

‘Modigliani Up Close’ is showing at Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia

Virtual world giving way to the real

‘Modigliani Up Close’ reveals how the Italian made his iconic paintings and sculptures. There are lessons for young people who want to take up art. When he arrived in Paris, he didn’t have a lot of money. But he was very good when it came to the use of materials. Young artists who may not have a lot of money to spend on fancy art supplies can look at his work for pointers.

“Looking” at his work involves seeing it in person and not just on a tech platform. It’s interesting to see important exhibitions return and at pre-pandemic scales. During the pandemic museums had to revisit how they were presenting art. Things were done through technology and it was something art curators hadn’t even thought about in 2019. Everybody had to reinvent themselves and what technology proved is that art can be brought to a much wider audience. A lot of people, who never looked at the big museums earlier, suddenly had art at their fingertips. Of course, the experience can’t be replicated. Even if you look at reproductions of Modigliani you won’t get a sense of texture or depth or even the variation of colours. What tech did is encourage people to return to museums. Many people — a lot of them young — became interested in art during the two-odd “virtual years” and they now want to see exhibitions in the flesh.

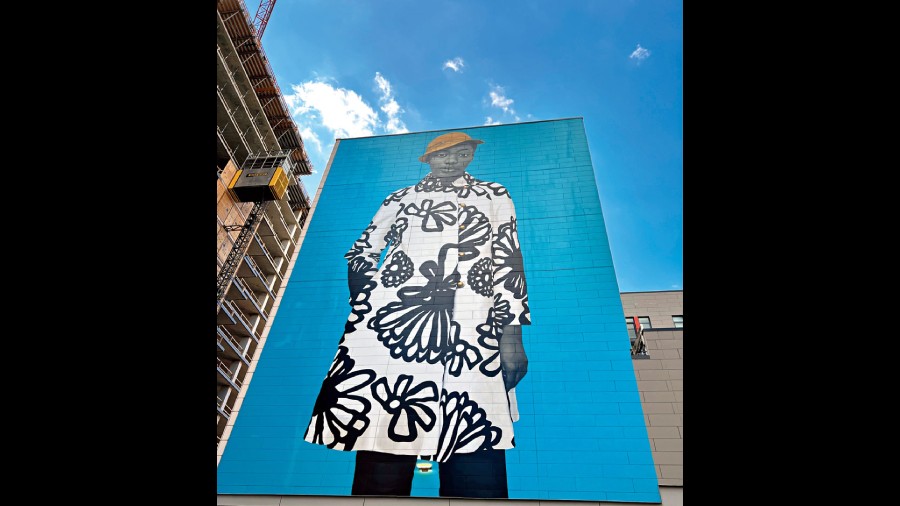

Finding Home by Kathryn Pannepacker and Josh Sarantitis

Times change, not always the mindset

The Modigliani exhibition is also a reminder that mindsets have evolved slightly but not changed. The year 1917 was historically important because Modigliani had his only life-time solo show. It sort of became a “notorious” showcasing because of the four nudes he had at the exhibition (he painted many more). It was censored after a local policeman who lived near the (Berthe Weill) gallery in Paris saw the nudes in the window and saw the pubic hair was visible. The paintings were asked to be removed from sight.

There has, of course, been anevolution as to how women are seentoday but there still are a lot ofproblems in many parts of the world.The censorship Modiglianiencountered was becausetraditionally nudes haven’t beenrepresented in the way he did. Hewas looking back at the olderclassical paintings but he was alsopainting very modern women and ina modern way. Sadly, 100 years on,some of the issues persist.

Amy Sherald’s towering Untitled mural

The inspiring story ofan art collector

A stone’s throw away from Barnes Foundation where the Modigliani exhibition is being hosted is the Philadelphia Museum of Art, which many know as the “address” of the“Rocky steps”. The famous Rocky scene has the fighter jumping up and down at the top of the steps, raising his arms in jubilation.

Inside, ‘Matisse in the 1930s’ resides with about 140 works from public and private collections in the US and Europe, ranging from both renowned and rarely seen paintings and sculptures, to drawings and prints, to illustrated books.

The 1930s was an interesting phase and it cannot be seen in isolation from the contribution of Barnes Foundation, which houses the collection of the great Albert C. Barnes.

The Barnes collection has been created by just one man, a self-made man, who was born into a workingclass family in Philadelphia in 1872. After working (he found support by playing semi-professional baseball) his way through medical school at the University of Pennsylvania, he developed Argyrol, a silver nitrate antiseptic which was used to treat ophthalmic infections among babies. Success followed and so did money. He could have practised as a physician but decided to follow a different path after completing his medical internship. He had the good luck to sell this company out to a big pharmaceutical firm in July-August 1929, just a couple of months before the big stock exchange crash. He reportedly walked away with several million back then.

But his painting collection started much earlier, in 1912, purely as a hobby. He sent his high-school friend William Glackens to Paris in February 1912 with only $20,000 to buy some examples of modern art, which he was reading about. This was at a time when Paris was at the centre of the art world, where all the innovations were happening. Artists from all over the world had descended on Paris where they lived freely, painting what they wanted to paint.

Glackens met dealers and artists like Picasso. He bought 33 paintings. These were by Renoir, Cezanne, Picasso, Degas, Pissarro… of course, there was more.

That was the beginning of the collection, one of the showpieces is Matisse’s 45-foot-long triptych mural, The Dance II, which Barnes had commissioned for $30,000. They were to be placed in the three roundheaded arches of the main gallery, positioned above a trio of French doors. Featuring geometric shards of blue and pink, the work has a group of grey nudes springing upwards and tumbling down.

Barnes looked at the paintings Glackens had brought back and found them so interesting that he decided to visit Paris himself. He met Picasso and bought more paintings from him. He bought what he liked. Up until the day he died in 1951, he was always buying, trading and swapping paintings. It was a very fluid collection.

Albert Barnes equally understood the importance of education. Inspired by the writings of philosopher John Dewey, Barnes, in 1922, chartered the Foundation as an educational institution for teaching people how to look at art. He wanted people to learn about art by looking at them instead of being told what to look for. The paintings in the galleries are not in any sequence; they are stacked floor to ceiling. If you go to a stately home in England or France, this is what you will get, a salon style.

The idea has always been to make the viewer comfortable admiring a painting instead of worrying about what others may think of it. Barnes also wanted people to understand how paintings are constructed. What we look at is a flat piece of canvas with paint on it. When the artist applies paint using lines, light, colour, space and geometry, a sense of emotion comes through.

What Albert C. Barnes had done almost a century ago is now being discussed by other institutions — the idea about rearranging collections to mix things up.

At The Barnes Foundation

Power in the paint

In Philadelphia, art doesn’t just reside in galleries and museums. It fills neighbourhoods in the way of murals. After all, Philadelphia is the ‘mural capital of the world’. What started as an anti-graffiti programme in the mid-1980s is today a visual delight.

The artists work with the communities while people from the community decide upon the theme and they are invited to help paint. Once an image is created, every colour is numbered, so anyone can paint. The themes are always socially relevant though not political. From issues such as homelessness to water conservation, everything that’s relevant gets represented. Mural Arts Philadelphia is unique and it helps capture a neighbourhood’s identity through art.

Acrylic paint is often used so murals can be painted, sealed, and repainted as needed. Depending on a theme’s relevance, a mural stays up for years, beautifying empty walls, parking lots, and other structures.

In case you are in the city, check out Michael Webb’s Tree of Knowledge, the colourful Water Gives Life by Eurhi Jones and David McShane (shows the city’s natural (rivers) and manmade (pipes) sources of water and the plants and animals that depend on them), Finding Home by Kathryn Pannepacker and Josh Sarantitis and Amy Sherald’s towering Untitled mural. In Philadelphia, blank walls are considered blank canvases. Here art is like nature, meant to be enjoyed by all.

Paintings, sculptures, murals tell stories. Art tells stories and brings us closer to the artists who created them. And Philadelphia is filled with such stories that you can cherish when you plan a holiday to the city of plenty… visually plenty.