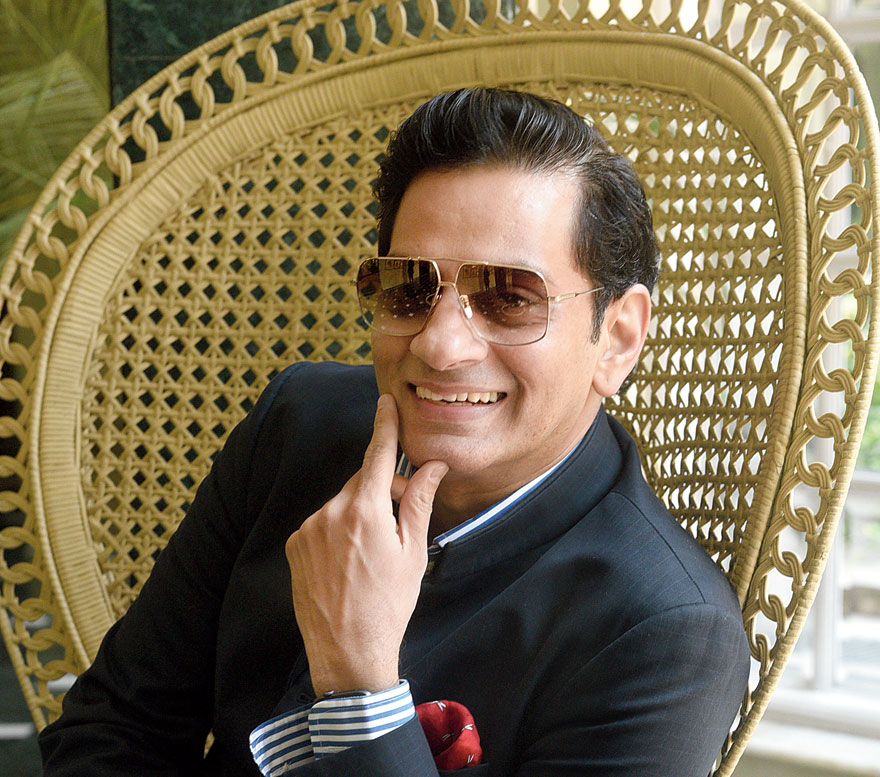

“I walked into the restaurant here last night and was surprised to see a framed picture of one of my grandfathers!” laughed Raghavendra Rathore when we met him at The Oberoi Grand on a sunny May morning. Punctual to the minute, he warrants adjectives such as “dapper” and “debonair” but those have been done to death when it comes to the leading couturier of the country. Runways, royalty and the razzmatazz of Bollywood, Rathore has been there, done that, which begs the question of “what next?”.

“Every person should try to leave a legacy behind, be it a Bajaj scooter, a Taj Mahal or the simple story of the bandhgala,” says Rathore. And he seems to have also zeroed down on that which is key for building that road — “The brand is bigger than the individual and the only way to survive the next decade is by getting the community involved.”

So how does that legacy live beyond the lifespan of the person behind the illustrious label?

“What I want to leave behind is a complete story and not something that is half-baked,” is Rathore’s assertive answer. Excerpts from a chat that unfolded with Rathore recounting his story and looking forward:

Royal heritage

It’s all good to reflect on royalty but it wasn’t all like this as we had to switch overnight from a particular way of living to another. And I always thought that the best analogy was that of a general without an army. All this idea of a regal paraphernalia was just an idea that was already in the past — at least to our generation. So my family was very grounded and my father (Maharaj Swaroop Singh) was an MLA from this rural area called Luni and my time with him in a jeep in the community was such a well-spent time, learning about the food, habits and culture. So for us the royal experience was very community-driven. My mother was extremely modern and a great intellectual — she would hide and read books when she was growing up. My father was protocol-oriented. So I had a good mix of extremely liberal parents but with a code of conduct. They never revoked the license of free-thinking but cautioned me to be earnest to myself.

When I told them I was going to study design, my dad just told me to keep Rs 40,000 aside in case of an emergency so that I could go to the airport and fly back. It’s about human-to-human relationships that need building and not pedigree and that’s how all of us during that time were brought up. You can’t choose where you’re born or your heritage but if you have it, then you make the best of it.

Coding to design

Once I finished college and moved out of India and went to study, I realised the consequence of the value I had picked up while on those jeep trips to those villages. I had never seen a woman’s bathing suit before — there was an indoor pool at Umaid Bhawan where we would hang out and we would have protocols and my first assignment in school was to design a swimsuit. I had gone to America to study robotics and I used to write code. Our programme was so beautiful at Hampshire College that it led you to what you were good at. The direction and advice changed my life. Those years of not learning design has given me the aptitude of being a designer today and that’s what I am doing at my new school — the Gurukul School of Design (in Jaipur). Marlboro College is where I enhanced my creativity and they directed me to Parsons School of Design in New York.

So all the engineering of the brand that has happened today is a very biological process than a strategised aim to start seed capital and all that stuff. We are doing that now but when we started it was raw, everything that your heart spoke to you. This is also why I got to work with people who were driven with emotion — Oscar de la Renta was an amazing experience and it’s a beautiful story to tell my children and the design team that not once did he say “What’s the new trend?”. The learning was that if people think that design is trendy, it’s a very superficial emotion as design is about human contact. It’s actually a philosophy.

The emotion behind the Bandhgala

Between two words — “emotion” and “story” — the product that we design has sustained over 20 years. What we do is a very basic design because we don’t even do a lot of embroidery. So how has this brand lasted? You just have to constantly remind people about the emotion that the bandhgala is — it is what our ancestors wore before Independence. There’s a story with emotion that does not need to change with seasons. The building of heritage in it reflects my exploration much later in my life that “Oh my god! The bandhgala was actually made by my great, great, great grandfather somewhere!”

We’ll fall flat if we were to talk about cutting-edge fashion because that’s not the DNA of the brand. If you bring those values and see your product around it, chances are that there’ll be more acceptance among the people. The bandhgala is a relic, I think. It can be versatile depending on how much you can oscillate your style. It can also be your ecospace and use it to add humour as well — I have made pieces with pictures of western actresses on the lining inside. It’s very important that you wear it the right way. I am perhaps the only one who advocated for the first two buttons to stay open and now everyone has started doing that.

Setting shop

In 1994, my cousin, Gaj Singh, the Maharaja of Jodhpur, was celebrating 50 years of the Umaid Bhawan palace and asked me to put up a fashion show. The bandhgala was still not in my conception and I was here visiting my dad and was still working with de la Renta. It took me two months to put it together and I didn’t know where to get sewing machines or even models or fabric. So I called up Suneet Varma and Tarun Tahiliani — it was a very help-oriented beginning.

I was a tailoring man and everyone here was doing long, fluid, embroidered stuff. I couldn’t find shoulder pads as I was doing tailored jackets. I remember putting Mehar Bhasin in a Jodhpuri jacket and people hadn’t seen that. It was a successful show as this wasn’t a traditional ethnic show, it was very east-west. The show happened at the oldest part of the Mehrangarh Fort. After the show Tina Tahiliani came up to me and asked if I wanted to stock at Ensemble. I was going to go back to America but requested for extended leave and started making a small collection for Ensemble and became a part of the fashion system in India.

But the community was so supportive because you cannot come overnight and get access. Rohit Bal helped me with the choreography, Tarun was a complete guiding compass in those days and Suneet helped me get my products and Geetanjali (Kashyap) helped me with models.

Thinking ahead

When we started, people were mesmerised because we were doing cuts at a time when everyone else was doing these flared silhouettes. But we sort of anticipated a bloodbath in the market about 15 years ago and completely shut our womenswear and completely focused on our menswear. The day we did that, I thought that we had stepped up to become responsible corporate thinkers as we became the go-to for bandhgalas. To perceive the bloodbath was very important and the innate decision of focusing our energies in a new market and taking that risk of being a menswear designer worked.

It gave us a hook in the market and the beauty of the bandhgala is that you can buy one in the market but it will never fit you the way one made for yourself will as it needs to go around your body and has to be tailored to the width of your shoulder and proportion of the length. When you hand-make anything, it sort of takes the print of your second skin. The bandhgala became the thing to wear, whether it be your wedding, anniversary or coming-of-age.

Art connect

I remember the first product I ever made apart from clothes was an art piece that sold at an Amfar (The Foundation for AIDS Research) gala outside of New York and I had Calvin Klein on one side and the world-famous artist Christo on the other side and it sold for a great price. It was called “Be Still My Beating Heart”, taken from a line of a Sting song, and it had a transistor sort of stuck to the wall. The price that it sold for is the single-most encouraging moment of my life. I paint a lot as that’s my passion. I think my passion really is in soul-searching and art. I have five commissioned pieces waiting for secret buyers who would, of course, wear my bandhgalas but also want my art on their walls (laughs). I don’t talk about my art because then my team is like, “Oh, he’s again going to go into hiding!” I also always keep an eye on what’s happening in the world of technology.

What’s changed?

For me, nothing much has changed as it’s the paraphernalia that has. My corporate and marketing people are the ones who perceive the change. But once the father gets his son to the atelier is when you are inculcating the heritage to further generations. Now, most people we have dressed are bringing in their children. We do not retail, it’s a bespoke business. A jacket can be worn for 10 years. Just like the sari, the bandhgala silhouette has been there for hundreds of years. For me, it’s about preserving heritage, observing the milestones that bring about change and to give back to society.

Giving back

The foundation of the business is based on a community approach, which I loved. I have started the Raghavendra Rathore Foundation to emulate the community spirit because whatever I have experienced, I would want to emulate. I did a huge U-turn two years ago when I said that we had to set up a design school because the kids have to see how the world is changing now. I had to fight with my internal board because we’ll have to sacrifice a lot of stores and divert funds into the school. But it’s now running and the first year is done. My experiences have helped with the tenacity to do more beyond my brand.

The Gurukul School of Design designs a course for India and it’s an attempt to solve the problem that we have as a tropical country. We don’t want people to pass out and say that they were not told that there’s no winter design market in the country. The methods and templates have changed. The course is designed with a mobile-friendly approach like life is now and it’s a homegrown course and the UGC affiliation gives them the B.Des degree. They need to know the business of fashion and how to sustain it.

The RR Foundation is keen to push the thought of these students giving work out to the lower strata of society so that they can become partners in creating products that the RR brand can absorb. The RR Foundation is focused on health and hygiene, and we also give work to four-five NGOs so that they can sustain themselves. So we have tried to create a sort of triangle, a trinity of the journey of my life.

The way forward

I believe that partnership is the way forward. The brand Raghavendra Rathore is now owned a little bit by Ermenegildo Zegna and Reliance investments. Raghu Rathore is now only me (laughs). The funding ensures that there’s no limitation. However, we are very cautious about how we expand. The first investment is in ourselves and then to have a strategy to recalibrate our entry and the new accessories will lead us there. I am thinking fiercely about upgrading the product and I want to compete with the international brands. The new investment will take six-12 months to show change.