Long long ago, the beautiful youth Narcissus went mad when he looked at his own image. The Greek myth could well have been about the first selfie.

Narcissus’s end was pre-ordained: when he was born, it was prophesied that he would live long “if he does not discover himself”. It so happened that the nymph Echo, “who cannot be silent when others have spoken, nor learn how to speak first herself”, quite beautiful herself, fell in love with him. But in his arrogance he told her that he would rather die than let her love him.

Scorned, Echo would wither away; only her voice would remain, forever. And Narcissus, fancied by many others, would one day chance upon an unclouded fountain, where he would see his own reflection for the first time.

One may ask here how he had escaped looking at himself so far. Even if glass mirrors were yet to be invented, would not a youth so vain have seen himself ever on another water surface? But we will let that pass and focus on Narcissus’ “discovery”.

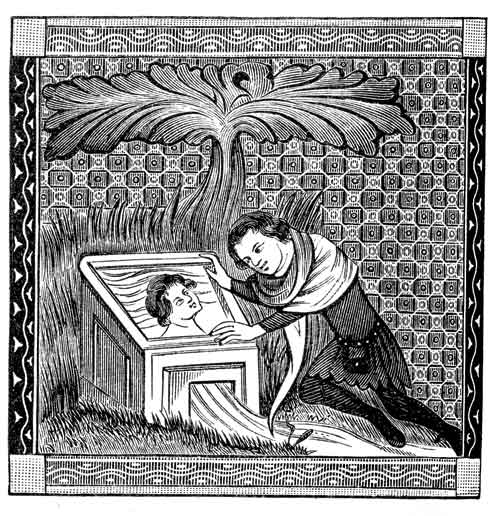

A 14th century illustration of Narcissus File Picture

On looking into the pool, he was stunned by his own beauty and fell in love with himself. Flat on the ground, burning with love, he wanted to touch the face looking back at him, but the moment he lowered his lips to the water, he shattered the

beautiful image. Narcissus, who would not stoop to love anyone else, would suffer from unrequited love the one time he loved someone, which was himself.

What else did Narcissus see? Was he really deceived that the image belonged to someone else? Or did he recognise himself?

Ovid’s account of the myth in Metamorphoses makes it quite uncertain. Narcissus does feel that he is looking at himself, yet does not either, because the cruel distance between him and his loved one keeps them apart, makes them two.

“I am he. I sense it and I am not deceived by my own image. I am burning with love for myself…What I want I have. My riches make me poor. O I wish I could leave my own body! Strange prayer for a lover, I desire what I love to be distant from me…Nor is dying painful to me, laying down my sadness in death. I wish that him I love might live on, but now we shall die united, two in one spirit.’

He is looking at his image and his image is looking back at him and his sense of self, caught in this complex web of gazes, is breaking down. Unable to resolve this contradiction, pining for himself, Narcissus dies.

Self-reflection, literally or otherwise, is hard. The mirror or the (self)-portrait can be a curse, as Dorian Gray, the Lady of Shalott or Snow White’s stepmother will also tell you. Self-portraits by acclaimed artists endure because they were explorations of their selves. However, tormented the artist is — Van Gogh, for example — he sees himself from a critical distance. Absolute self-absorption, which can be a function of extreme beauty, makes perspective disappear. Neither is it good for the self, nor for the portrait. Everything else is rendered invisible if one does not see beyond oneself and the image remains elusive in any case.

But it will be tragic to end with this moral. All of us do not need to be great artists, and are not extremely beautiful. And Narcissus lives on — not only as the flower but also in each one of us, especially in the age of selfies.

Whatever others may think of us, most of us find ourselves beautiful. How else do we explain our urge to take selfies forever? To go on looking at the camera? Somewhere we, too, hope to capture that beautiful person whom we have glimpsed in us (go on, laugh), who continues to prove elusive. Do we feel a little bit of the fascination and the terror that Narcissus felt, holding on to our illusions? Do we wonder who that person is in the camera? And unlike Narcissus, do we feel a little self-conscious, embarrassed? Our Instagram begins to fill up. Our followers echo us with their likes.

Beauty is a need and technology helps. We have upgraded Narcissus, though: we have added the pout.