A story from Kerala folklore that captivated public attention in recent times is that of a lower caste woman chopping her breasts off and handing them over to a tax collector in defiance of the breast tax, or mulakkaram. This tax, as some accounts suggested, was levied to ensure that lower caste women could not afford to cover their breasts.

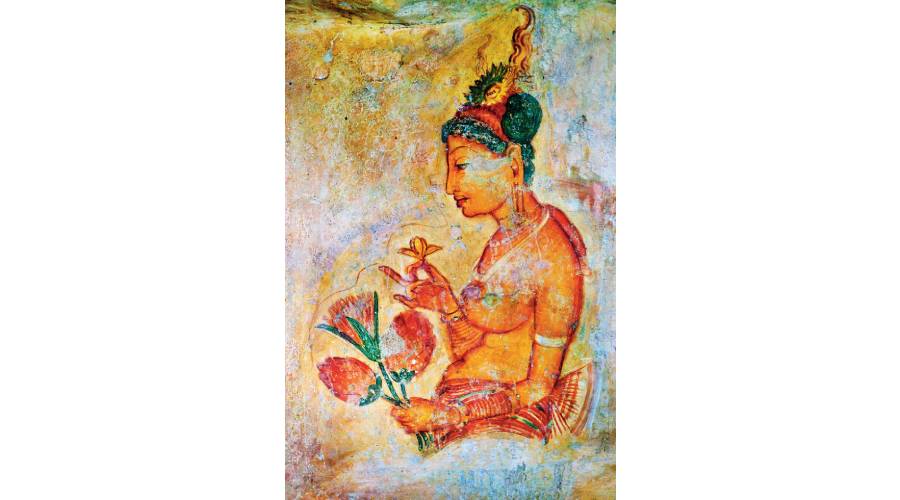

That there was a tax on lower caste women in the earlier centuries in parts of Kerala is a fact. But that it was meant to prevent them from covering their breasts in particular seems a bit farfetched, as even royal women, including queens, did not cover their breasts in those days. “Not until the 1860s,” says Manu Pillai, historian and author. What the upper castes carried instead was a shoulder cloth denoting their exalted stature.

Before the British imposed their Victorian morality on the region, “covering the torso was not seen as a mark of modesty or virtue for men and women”, continues Pillai. An illustration of the Dutch traveller Johan Nieuhof visiting the Queen of Quilon in the mid-17th century royal court shows her with her upper body uncovered. The accounts of Italian visitor Pietro Della Valle, from the same century, refer to, in Pillai’s words, “the Zamorin Rajah’s sister and nieces who appeared in durbar with just silk cloths round their waists, a lot of jewellery, but no upper covering of any kind, not even the shawl...” This, too, dilutes the theory of the lowest caste women being forced to remain bare breasted.

The breast tax was not about the breast alone. It was about the entire body. So how did the breast tax come to be named so?

“Beyond the name it had nothing to do with breasts. It was just to distinguish between the sexes. It has been misunderstood as a tax for the right to cover breasts — there was no such tax,” says Pillai, firmly dismissing the notion of the lower castes being prevented from covering their breasts in Kerala.

J. Devika, a historian at the Centre for Development Studies, Thiruvananthapuram, agrees. “Men and women, both were expected to leave their chests open. The upper cloth was a mark of the upper caste.”

Lower castes had to pay to be entitled to their entire bodies, not only a part of it.

But what was mulakkaram? What was its quantum? Which transgressions invited its application?

“We don’t have a lot of records. But it was a normal tax. It was levied on the patita jaati workers,” says Devika. Patita were the fallen women of the lowest castes like Ezhava, adds Devika. The interesting point is that similar taxes were levied on lower caste men, too: the head tax and the moustache tax, talakkaram and meeshakkaram respectively; the nomenclature chosen for the male gender.

If that is so, where does the folklore about women cutting up their breasts in order to demand the right to cover them up, originate from?

“The gesture of chopping off the breasts was the refusal of the brahminical swarga on earth, bestowed to Brahmins by Parasurama, and for which the lower castes had to pay a tax. These women were not struggling for feminine modesty. They were asserting their right to their bodies, freeing it from this order even though that meant mutilating it,” Devika adds.

Folklore often remains restricted to oral transmission and rarely makes its way into recorded history. Other elements enter through the gap.

The story of a woman named Nangeli cutting off her breasts and offering them to the collector gained currency after a recent painting by Murali T became popular. The painting was followed by a short film on the same subject by Yogesh Pagare.

The tradition of not having a stitched cloth on one’s body while visiting certain temples in south India still continues. Of late, women have been granted concessions in their dress codes during the temple visits. Men, however, have to remain strictly stitch-less when gaining entry to the premises. This norm was followed in parts of north India and Bengal, too, where women wore an unstitched sari, and no more, especially while cooking and worshipping.

The bigger question is this: despite contemporary global laws that are freed of sexual bias, has the modern woman actually defined for herself what respects her own body? On a lighter note do we realise that even today, we women are mostly naked when dressed up, while men aren’t?

The columnist is the founder-CEO of Necessity-SwatiGautam, a customised brand of brassieres. Contact: necessityswatigautam@gmail.com