Clothes are a paradox in the way they are meant to robe the wearer’s body and their consequential disrobing of the wearer’s personality. Historically, we have learnt about epochs and their cultures through their respective clothing habits. More recently in the subcontinent, the politics of what we wear has also been underscored by attaching them with the objective of serving as communal identifiers. Every piece of clothing seamlessly captures the zeitgeist of our troubled times within each of its folds and creases. And “clothesmaker” Kallol Datta knows more than just a thing or two about that.

The Jameel Prize

Fresh from getting shortlisted for the prestigious Jameel Prize in its sixth edition and its first thematic iteration that is curated by Rachel Dedman, Kallol is all set to showcase a collection of works that will open at the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in London in September, before it tours internationally. The Jameel Prize is held in collaboration with art organisation Art Jameel and the V&A to recognise and celebrate contemporary art practitioners who are inspired by Islamic tradition and culture and the winner is set to be awarded £25,000 this year. Incidentally, the theme for 2021 is “Poetry to Politics” and anyone who is familiar with Kallol’s practice of art would by now have had an “aha” moment regarding how he fits so snug within this context.

For the uninitiated, Kallol, “on a pathological level” has never cared for conformation but has always done what he believes in, since starting his eponymous label in 2008 as he has continued to make clothes that do not adjust according to the wearer but is the other way round. Over a recent phonecall, he explained the shortlist: “To be very honest, I just applied for it because I was nominated and I don’t know what I was expecting but it seemed like a natural fit, considering the work I do. If you see the other seven finalists, the works are amazing! Super powerful, emotional and meaningful.”

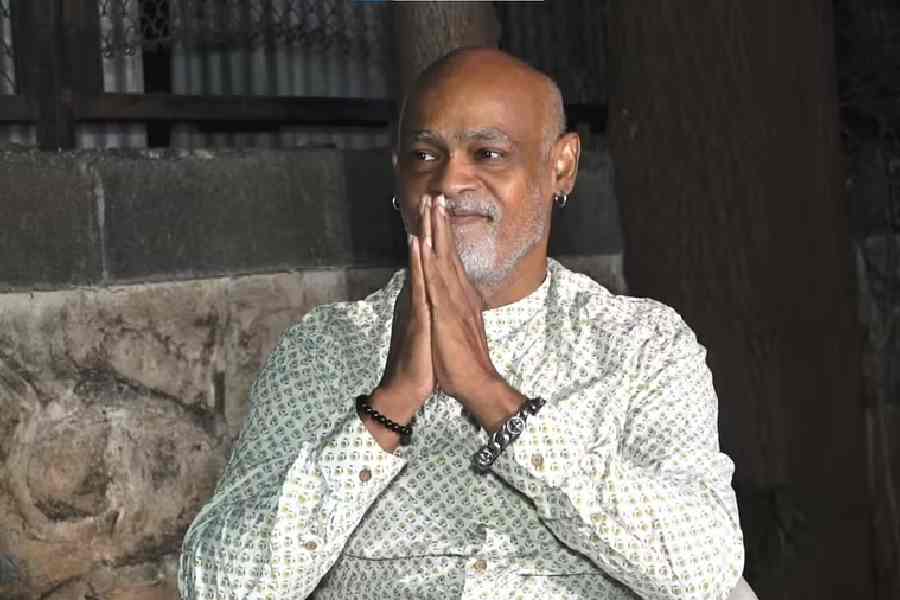

Kallol Datta Picture: Navonil Das

For the exhibit, Kallol will be showing textile-based works and images across three clothing projects, namely Volume 1; Volume 1, Issue 2; and Volume 2. “The work that will be exhibited is very indicative of the kind of work that I have been doing over the last few years — it has got my signature pattern-cutting and I do a lot of creative research for any project and that comes through too for the viewers and observers,” he said.

The image used for the announcement of the shortlist by the organisers is captioned Look 4, Volume 1 and shows a bright hue that captures Kallol’s occasional departure from his usual monochromatic mood board. “That was a very colour-heavy line and it was just what I was feeling at that particular time while working on it. But I really enjoy working with colours as there is always a certain desaturation to it or always a certain finish to the colour. It’s never going to be bright, for lack of a better word,” said Kallol.

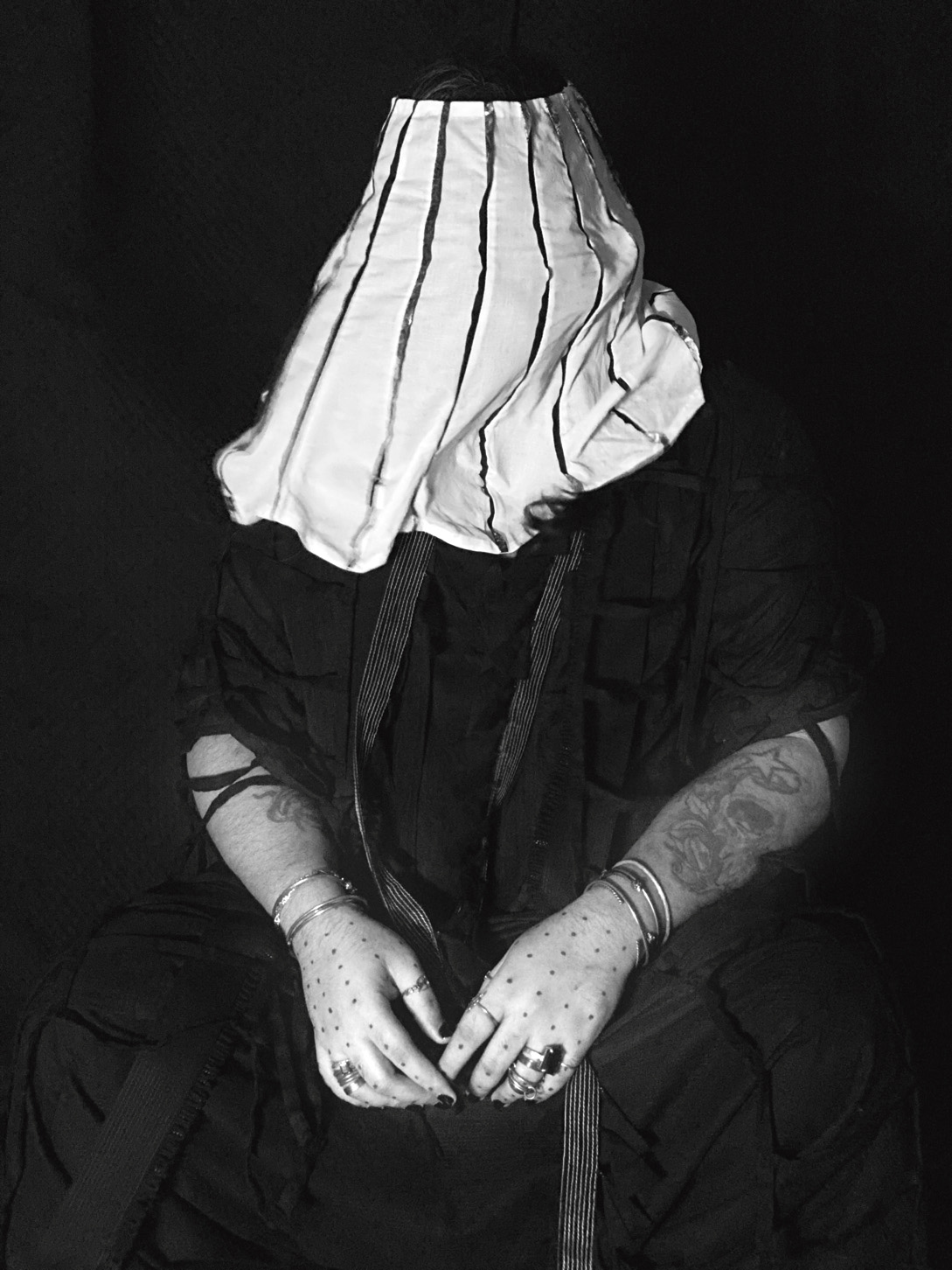

(Above) Twisted, Volume 1 Issue 2, 2018; (Below) Shroud, Volume 1 Issue 2, 2018 Pictures: Keegan Crasto

Clothes as a canvas

At a time wrought with politics of a very volatile nature, the theme of the prize is indeed resonant. So I imagine it held more interest for the Calcutta-based designer who has never shied away from using his clothes as a canvas for postulating uncomfortable questions. “When I was younger, I would always approach it from an instructional point of view where you get to learn about different cultures and civilisations because of clothing artefacts or sculptures whose clothing reliefs you could study to get a better understanding of that time. And now, you have countries banning the veil where there is a mask mandate at the same time and you have to have it on when you’re in public. Just because it’s a medical mask and constructed a certain way, it is acceptable for medical reasons, which are understandable. But just when someone dons the veil because of religious practices, it becomes a public debate. These are extremely weird times we live in and clothing is a great way to talk about it and make my point of view come across,” Kallol concurred.

And Kallol has fearlessly been putting forward his point of view for over a decade now, without bowing to accepted norms of “fashion” or giving into the hyperboles associated with the film industry that are often considered to be the yardstick of success in the Indian context.

Images from Volume 2, 2019. Pictures: Parak Sarungbam

Image from Volume 2, 2019. Pictures: Parak Sarungbam

This made Kallol say, “At the onset, more than me getting apprehensive, I guess it was people around who were anxious for me, which is why I was constantly told at the beginning to introduce an element of visual interest in my clothing. They always felt that the observers here would not get shape, form or silhouette. That is why I introduced prints into my work. I slowly weaned that off and I’ll only access print stories if I feel it goes with the narrative of a project.”

Swaddling to shrouding

The Middle East-bred, NIFT and Central Saint Martin’s-educated Kallol’s practice in design has been reflective of a preoccupation and an eventual evolution in his study of shapes, especially those inspired by native wear of the Nawa (North Africa West Asia) region, the Indian subcontinent and even the Korean Peninsula. “I take the native-wear shapes that have almost become template-like forms and I introduce distortion in them through pattern-cutting and then I layer it and all of that forms certain shapes and silhouettes. I do that because I find so many similarities — say between the Korean hanbok and the Indian angrakha to certain abaya forms in Western Asia. So it becomes like a template-based wardrobe or a capsule of sorts. I find that fascinating. I have always been interested in clothing practices — the way people shroud, swaddle and layer,” explained Kallol.

Looks from the designer’s collection titled Low Res that was showcased at the Lakme Fashion Week in 2016. Pictures: Sandip Das

And doesn’t that encompass the inherent politics of our identities? — I ask him. “Oh, yes! Like I always keep saying that we become immediate visual markers of our communities. And it is prominent when I try to grapple with notions of cultural sustainability versus notions of cultural diversity. But how does that play out? Forget countries or regions where the population is homogenous. In a region like ours, which is so diverse, I feel like we are at loggerheads with cultural sustainability on one side and cultural diversity on the other. So those are the conditions that I am always trying to address and not particularly answer. I try to create design interventions through my work and let that carry on forward,” answered Kallol.

Two words that struck me from what he said were “distortion” and “diversity”. Are they mutually exclusive in his work or are they reflective of a conflict in the underlying themes that he works with?

“Not literally but in just the way I pattern-cut, there’s already some conflict involved with, let’s say, the body that it will enclose. Normally the clothes are made according to the body it’s being placed upon. For me, it’s the other way round. The body which inhabits my clothes will have to adjust according to my shapes. My clothing is not going to adjust for them as such. I cut my clothes upon a certain axis and have certain control points,” said the designer, implying the presence of tactile conflict that is not so literal or blatant.

Looks from the designer’s collection titled Low Res that was showcased at the Lakme Fashion Week in 2016. Pictures: Sandip Das

A non-conforming democracy

However, he makes no bones about his distaste for a frenzy-inducing manic pace of fashion and a publicity machinery on overdrive that tells the Press what to publish, starting from who the intended customer is to what not to write, as he said, “Do you remember when we used to have these Press releases saying this collection is for a global woman who is comfortable wearing her salwar-kameez at an art gallery in Milan? That was so inane! If that’s the kind of profiling you would do — and I am against profiling of any sort — that’s insane! What happens on the flip side is that it becomes more democratic where anybody — non-binary, men, women whoever wants to partake in my clothing is more than welcome to!”

His insistence on being called a “clothesmaker” bears testimony to his commitment towards not adhering to the trending norms of clothes-making. But Kallol is more than willing to pass on the knowledge he has accrued through his research, experience and his inventive approach to future generations. “I just don’t want the future generations of clothes-makers and fashion designers to be vapid creators. It’s not good enough in the present economic and socio-political climate to say ‘I made a collection inspired by love or nature’. That’s cute but no, you got to get more involved!” said Kallol.

And as for what’s next? Apart from finishing Volume 3 and figuring out how the showcase for it works out, he is happy to take a week at a time for now, as he goes about his day’s work and moves on to enjoy his favourite East Asian dramas!