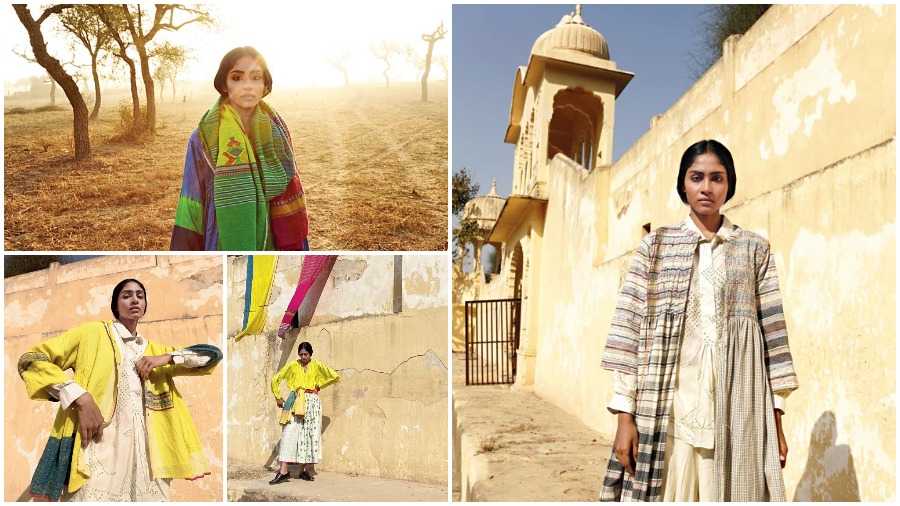

With a firm focus on textiles and her heart in sustaining the craft traditions of India, Chinar Farooqui (inset), founder and designer of Injiri, has relied on her personal experiences to tell stories through the lens of her label and her times spent in Rajasthan and Gujarat, which lie at the core of the brand. While debates about the ownership of Indian heritage crafts is a raging topic, Chinar aims at a more practical solution of sustaining relationships with her weavers by helping them sustain their livelihoods through collective ownership. With their latest collection called Shekhawati, Injiri has put forth “a colour palette featuring green, yellow, pink and blue; Merino washed wool from Gujarat, pashmina/cashmere from Kashmir, silks that are merged with the extra weft technique, bandhani of Kutch and pochampally from Andhra Pradesh” to present craft legacies of the region. In a t2 chat, Chinar talks craft and creation:

What is the ethos of Injiri and what is its design vocabulary, according to you?

Having grown up in Rajasthan, it is at the core of all that Injiri does. I am deeply inspired by the local dressing of the nomadic tribes, drapes and use of colours and silhouettes, and often I turn to the people to find inspiration from the everyday (dressing).

For me, Injiri is an expression of beauty that lies in the textile design heritage of the country. To achieve beauty, one does not necessarily have to do something “different” but reinterpret the classic forms, some of which have been lost along the way due to the changing socio-economic structure of India and, of course, popular culture.

So, I would say my design vocabulary is a mix of India of the past and India of today, modern yet rooted in tradition.

The key ethos centres around making sure my work supports Indian living traditions of textile crafts. We ensure that we are working with the same weavers through the year and the relationship is very important to us.

The visual language that we choose to work with for each craft comes from an artistic bent of mind rather than a commercial one. This makes our products appeal to many.

Tell us about the new collection — its moodboard, the textiles and the designs.

At Injiri, we redefine the traditional clothing styles, keeping their true essence alive, for we truly believe in the absolute beauty of simplicity. Working in close quarters with weavers and their style vocabulary, we are constantly engaging in dialogues with these keepers of the intangible human heritage of a time that is almost bygone. The Injiri repertoire is born out of a cluster of inspirations ranging from weavers we work with to antique pieces of clothing. However, simple, everyday clothes worn by peasants, farmers and the common man inspire us the most.

We continue to work with the same set of weavers season after season as the brand’s connectedness and sustaining of these relationships is a core philosophy. For example, for nearly a decade, I have worked closely and built an understanding and relationship with the master craftsman of the Bhujodi tribe — Shyamji Bhai. This relationship of trust and understanding helped convince him to experiment and rework the core wooden structure used for wool weaving by the cluster that helped create wool garments in our latest collection that are super soft and light yet comfortably warm.

Also, each of our collections is a mix of multiple crafts and techniques. For example, in Shekhawati, you can see us experimenting with colour blocks, and a predominance of green, yellow, pink and blue brought together by Merino washed wool from Gujarat, cashmere from Kashmir and rich, luminous silks and merge it with the extra weft technique and bandhani of Kutch and pochampally from Andhra Pradesh.

After a year of being locked down at our houses, I wanted to work with colours as an idea to create beauty — colours are abstract yet so effective in the emotions they create for us and that’s how Shekhawati was conceptualised. As artists and designers, colour is a very strong tool that allows us to work with how we perceive beauty. When I look back at the collection, I find that my work is influenced by the visual aesthetics of Gujarat and Rajasthan, both states where I have spent a significant part of my life. The collection is also shot at Shekhawati, a region in Rajasthan which is very well known for its rich cultural heritage, such as wall frescoes.

Our work is heavily inspired by the traditional architecture of Rajasthan. As a brand, our process centres around working closely with handloom weavers and their vocabulary across various parts of India; our design stories start with curating and studying old pieces of textiles, which showcase the crafts at their purest forms.

As a craft-intensive brand, what are the areas of focus that a designer has to be mindful of in today’s times? The ownership of crafts is a hot topic of debate at the moment. Given your experience of working with weaving and craft communities, what do you think the main areas of concerns are, and how could we, as consumers of fashion, do better?

For every designer out there working with crafts and for us, I think the most important thing to keep in mind is how to create designs that add longevity to the craft and provide the artisan with continued monetary gratification.

One cannot work with a craft only for a single collection. Therefore, it is our responsibility to find long-term use of clusters and their work, thereby providing avenues for the continued employment and sustenance of the form.

India has a legacy of textile crafts. Every individual has had one form or another intrinsically tied into their everyday lives. For me, there is no one owner of a craft, but it is collective ownership. With that collective ownership also comes the need for collective responsibility to find ways in which the lack of patronage does not lead to the dying out of these forms.

We need to see that we continue to support the craftsmen by buying products at a better rate; while negotiations are an essential aspect of business, quality mustn’t be compromised in the name of profit margins or making things more affordable. The time-intensive work that goes into the creation of Indian textiles is at par with the West’s luxury products, and we have to accept and appreciate them through the same lens.

Pictures: Courtesy of Injiri