The painting on the wall shows two ebony male figures with bows and arrows. “Sidhu and Kanhu,” says Ruby Hembrom, by way of introduction. “They are very important for us, the Santhals. This painting is also by a Santhal, an artist named Saheb Ram Tudu,” she continues. Sidhu Murmu and Kanhu Murmu were Santhal leaders; they mobilised about 10,000 Santhals in present-day Jharkhand and Bengal in 1855 in an armed uprising against the landlords, moneylenders and the British.

The 41-year-old Hembrom is the founder of Adivaani, an “archiving, chronicling, publishing and disseminating outfit of and by the 104 million indigenous peoples of India”. The word adivaani means the Adivasi voice. In India, Scheduled Tribes are broadly referred to as Adivasis. Santhals form a fraction of these Adivasi people. Throughout this interview, however, Hembrom uses the two terms interchangeably.

Hembrom moves her hands animatedly as she talks. She is dressed in a floral cotton dress, has a resolute face and a way of holding your gaze throughout the conversation. She says, “Since its inception in 2012, Adivaani has produced 19 books,” and her earrings swing determinedly.

Hembrom’s family had shifted from Benagaria village in Jharkhand to Shillong and then to Calcutta in the mid-1970s. “There was some conflict with the church leaders because of which my father and his students had to move out,” she says. In Calcutta, he taught at the theological college, Bishop’s College. Says Hembrom, “We come from a culture that has an oral tradition. Engaging with textbooks was really difficult.”

Courtesy: Ruby Hembrom

At the Hembrom residence, Santhals living in Calcutta would gather every now and then to discuss culture and politics. Many of her father’s friends too would contribute to the Santhal newsletter, Jug Sirjol. Hembrom’s mother, Elveena, assisted the treasurer, and her father, Timotheas, was its editor for 30 years. Jug sirjol meant a new era. She says, “None of them were professional writers, but they wrote. It was not just a cultural expression, there was also political commentary.” When Hembrom started Adivaani, the first book off the press was a Santhali translation of a part of her father’s doctoral dissertation titled Santal: Sirjon Binti Ar Bhed-Bhangao, which is about the Santhal people, their way of life and so on.

School wasn’t a happy place for Hembrom. She says, “There was no one who looked like me. Being Adivasi means your features, your face, they tell your story.” Her classmates would ask her if she polished her face when she polished her shoes. When she said she was an Adivasi from Jharkhand, she was asked if she ate humans or lived on trees.

Years later, when Hembrom completed her law degree and joined the IT industry, she realised she was the only Adivasi in her work sphere. “Even during recruitment for the most basic employment opportunities, I saw no one from the peninsular region or the Chotanagpur plateau. Either these companies were not going to Adivasi areas or we were ineligible. And then I thought maybe it all made sense because if you look at us, most of us are uneducated. Even my first cousins in the village have not been able to complete high school,” she says and pushes away a strand of hair that has been disturbing her for a while now.

Hembrom blames this on the language trap. She says, “We are educated in a language that is not English and that makes us redundant in the larger society. How far can you go if Hindi and/or Bangla is all that you know other than your mother tongue?” She continues, “Just imagine, it is this one language, English, and my ability to speak it that has enabled my entry into spaces that have been closed to us for so so long. And I thought I have to teach my people to communicate in English.”

Courtesy: Ruby Hembrom

And so in April of 2011, Hembrom quit her job and signed up for a publishing course. She says she knew she wanted to make a difference but was not sure how. She was thinking on the lines of educating young Santhals in English and telling them about their history. “If not now, these stories are going to be forgotten. It had to be done,” she says.

The history of the Adivasis has always been written by others — the mainstream historians. While the Adivasis treasure their cultural and historical legacies, there is next to no documentation of this by themselves. Says Hembrom, “We may have a shorter history of writing but we still write in our native language. Santhali is written in five official scripts — Bangla, Devanagari, Odia, Roman and also Ol Chiki. But if you look at Adivasi writing — as opposed to writing on Adivasis — it is usually self-publication, because no one wants to publish us.” It was also beginning to dawn on her that one reason Adivasis were easy to overlook was because they didn’t themselves write in English.

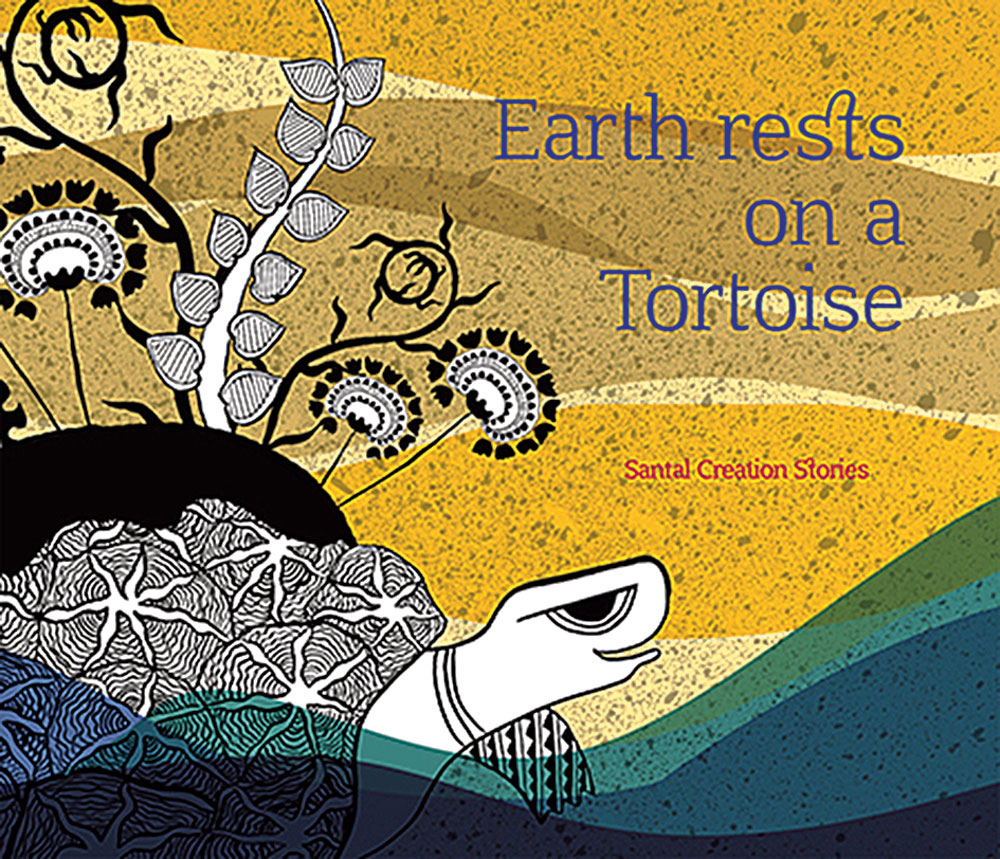

Hembrom realised it was important to begin at the beginning — write stories for children about how the community came into being. She says, “I have grown up bereft of many stories and people in villages too are no longer growing up in that tradition. Not because they are displaced by their regions but because of changing lifestyles and taking over of our lands by mining companies. You go to Jharkhand, you will see grandparents and grandchildren working in stone quarries. Where is the time to sing or tell these stories?”

We come from the Geese is about the creation of the Santhals from the geese couple, Has and Hasil. Since it was a book for children, the creative thought had to extend to visual representation as well. For instance, there was that struggle to find a fitting representation of Thakur Jiv, the Supreme Being. In the end it was decided that Thakur Jiv would have larger eyes and the subordinate beings — Bongas — would have smaller eyes. The rest was up to the children — they could give the Supreme Being the gender they wanted, any form they imagined.

Courtesy: Ruby Hembrom

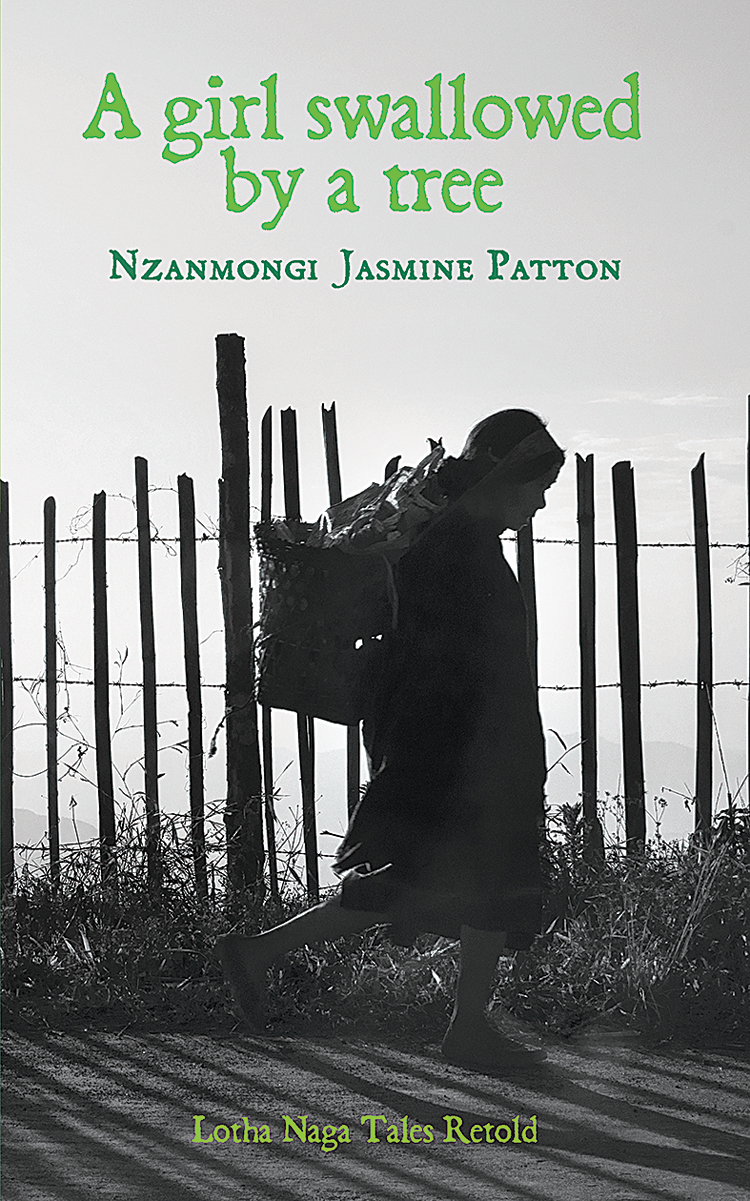

Hembrom thought it would be a good idea to bring out a book which would introduce people to Adivasi issues in peninsular India such as corporate crimes, poverty and other development-induced problems. All this came together in the book, Whose Country Is It Anyway. Then there is Becoming Me by Rejina Marandi — a book about Liya, a young Santhal from Assam and her struggles against the backdrop of ethnic riots. Nzanmongi Jasmine Patton’s A Girl Swallowed By A Tree is a collection of 30 folk tales from the Lotha tribe of Nagaland. Bodhi Sainkupar Ranee is the national co-convenor of the Tribal Intellectual Collective of India. He edited Social Work In India: Tribal and Adivasi Studies, perspectives from Within (Volume 3). He says, “We work with Adivaani to publish some of our work and material. These books are academic pieces compiled by the Adivasi faculty teaching in colleges and universities.”

As Adivaani gained literary traction, Hembrom’s mail inbox was flooded with manuscripts. “It was very interesting material but it was mostly from non-Adivasis. I told myself this platform isn’t really for them because if they take their writings elsewhere, they will get published. It became very clear to me at this point — this platform was going to be exclusively for Adivasis,” she says.

The journey from book to book was not entirely smooth. Hembrom gets agitated as she details some of the affronts she has had to face. She says, “Once people learn you are an Adivasi, they try to assume power over you.” People have also criticised her for using English and have asked her how Adivasis even engage with it. Says Hembrom, “It is about existing. Nudging your way to shelves and marking your presence.”