When C. Lawm- zuala of Mizoram University’s Central Library and Lallaisangzuali, a deputy librarian there, decided to set up a tiny non-profit roadside library in the capital Aizawl in 2020, they could barely have imagined the range of inspiration their magnanimity would ignite. The duo had seen similar reading nooks during their trips to the United States and decided to replicate them once they returned home.

Their venture in a state with a fairly high literacy rate has led two sisters in the border state of Arunachal Pradesh to follow suit by establishing mini roadside libraries in three remote districts — Papum Pare, Kurung Kumey and Tirap.

Ngurang Meena, a 33-year-old schoolteacher, and her younger sister Reena, a PhD scholar at JNU, New Delhi, had launched the Ngurang Learning Institute (NLI) in 2014. When all activities came to a standstill during the pandemic, Meena, who had seen a Facebook post on the Mizoram roadside libraries, decided to open one in her village.

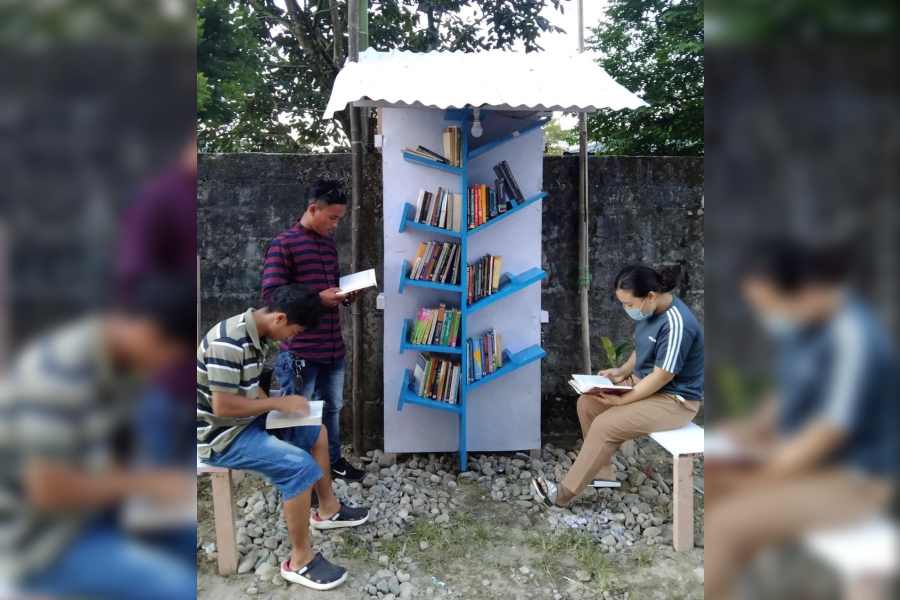

Library for All: In remote Arunachal, books on the streets and on trees too!

The hurdles were many. As Reena says, unlike Mizo-ram, Arunachal Pradesh lags behind on many para- meters. “The state is the worst performing compared to all its ‘sister’ states, and most of the Indian states, notably in literacy. It is also the second lowest performing state on NITI Aayog’s Sustainable Development Goals index on gender equality and among the lowest performers in quality education,” she points out.

In a span of three years, the siblings have done the state proud. The United Nations General Assembly recently recognised their Free Street Library Initiative as an exemplary project. The articulate Reena, when asked about the UN accolades, says, “Our journey to the United Nations General Assembly has been possible due to several factors, distinctively the love and support from Arunachal

society, friends and well- wishers such as writers, human rights defenders, and cultural institutions in India and abroad. With the recent UN recognition, I am convinced that NLI will continue to persist with its humanitarian and educational efforts, notably with the cooperation from the international community.”

Started with an initial fund of Rs 10,000 for books and an equal amount for wooden shelves, today the 26-odd street libraries, some simply comprising racks in the crevices of trees, have their own stories to tell. Meena, who is a teacher at Kimin Higher Secondary School, had to devise ways to inculcate the reading habit in children. This included luring them with treats and gifts, once the excitement of seeing new books had faded.

“Through partnerships with various educational, cultural and non-profit institutions such as the Papum Pare district collector’s office in the state, NLI has been able to amplify its outreach and impact on literacy. These partnerships, along with contributions from several other individuals and entities, enabled the project’s gradual launch of the second phase in 2021-2022 to eventually become a statewide movement. During this phase, NLI received support from the British Council, Roli Books and even authors like Bee Rowlatt, a British journalist and feminist author,” Reena adds.

The libraries thrived during the pandemic because schools were closed. Once the educational institutions reopened, the footfall dropped considerably, from nearly a hundred visitors a day to between 20 and 40. Meena, along with her partner Diwang Hosai, continues to spearhead this unique literacy campaign.

Meena says, “Since I had a lot of free time during the lockdown, I started leading many children in and around my neighbourhood to read books from this free street library. I had a firm conviction of introducing them to books. Only a few days after the library became functional, I saw so many children spending a considerable amount of time with books. It was so liberating for me to see them read. When I saw the library having many positive effects, I got even more encouraged to extend this idea of mine. Even Prime Minister Narendra Modi applauded our efforts in Mann Ki Baat.”

The initial pitfalls were the vagaries of nature that resulted in the collapse of one such library. Sometimes books were stolen. Now, with international recognition, the sisters hope to extend their venture to all districts in the state, especially the remote border ones. As Reena says, “There is now focus on infrastructure development in areas bordering China, since those are of strategic importance. That is a blessing since there is no WiFi in villages like ours. It is difficult to sustain on phone data. Often there is no electrification or network is poor.”

On the ground, it is primarily Meena and Disang who run the project from their base in Nirjuli town in Papum Pare district. The Arunachal government even honoured Meena this year as part of International Women’s Day celebrations. Those who frequent these open-shelf roadside repositories of books are mostly children under 10 and working women. Reena explains that they “approach local government schools to research the reading habits of students and seek donations on social media to keep this unique venture viable”.

As the first woman in her family to pursue higher education, Meena values books because she had limited access to them while growing up. Today, as a teacher, she is concerned over the poor writing skills of students and is determined to inculcate the reading habit in them to overcome this handicap. The UN feather in their caps will hopefully propel the library dream to take wings and help the state tiptoe out from the “worst performer” box!