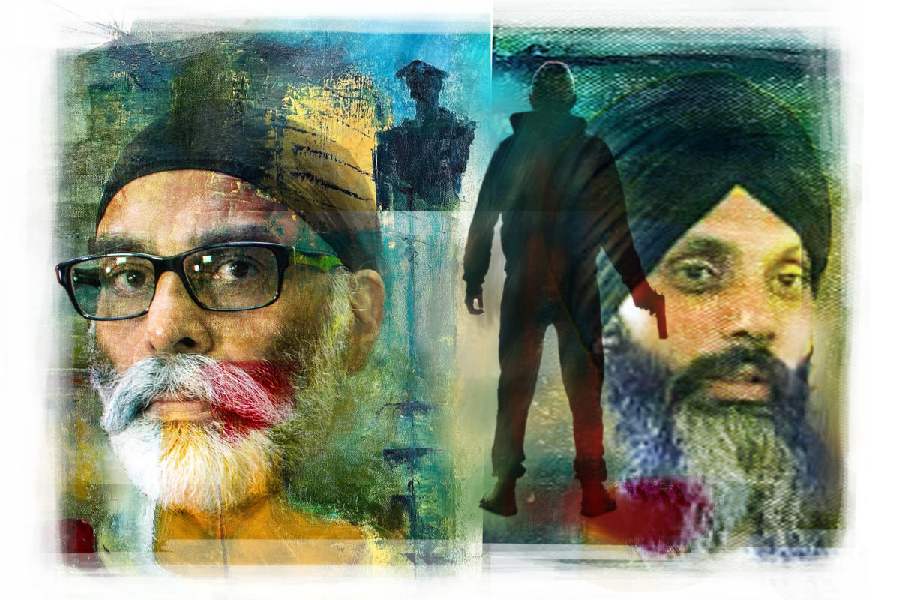

A few days after Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau claimed that his government had “credible allegations of a potential link between agents of the Government of India and the killing of a Canadian citizen, Hardeep Singh Nijjar”, India’s external affairs minister S. Jaishankar was in the United States for his routine pilgrimage of various think tanks. “We told the Canadians that this is not the Government of India’s policy,” said the diplomat-turned-politician, who has become the voice of the Hindutva establishment in foreign capitals. The external affairs ministry spokesperson repeated it. When the US raised the foiled plot to assassinate New York-based lawyer Gurpatwant Singh Pannun, the Modi government told them at the senior-most levels “that activity of this nature was not their policy”.

If it were the British instead of the Americans, they would have perhaps responded with Sir Humphrey’s immortal line from the famous television series, Yes Minister: “No, no Minister! It could never be government policy, that is unthinkable! Only government practice.” Weeks before taking over as Modi’s national security advisor, Ajit Doval had publicly advocated a “paradigm shift” by using “intelligence-driven operations”, wherein “to defend ourselves, we will go to the place from where the offence is coming”. Two years earlier, he had asked the Indian intelligence to develop “proactive and interventionist operational actions”.

Irrespective of whether his proposals became policy or practice — or a philosophy — under Modi, the evidence of an official Indian connection to the plot to murder Khalistan supporters in North America is hard to rebut. The superseding indictment filed by the US Department of Justice may have only named Nikhil Gupta, who is now in custody in Prague, the Czech Republic, trying to fight his extradition to the US, but it is the Modi government and its security establishment, led by Doval, that has really come under the Biden administration’s scanner.

The US State Department spokesperson called the murder conspiracy a case of “transnational repression” an expression Washington DC usually associates with the authoritarian regimes of China, Russia and Iran, when they use threats or violence to silence dissenters living abroad. Modi’s “New India” joins the list, razing the country’s hard-earned global reputation as a responsible power which largely played by the rules. India was mentioned several times last Wednesday during a hearing on transnational repression held in the US Senate, wherein lawmakers mostly focused on human rights abuses by China, Russia and Iran. “It’s one thing to deal with this behaviour when it comes from a nation that we would sort of put into the adversary camp — China, Iran, others,” Democratic Senator Tim Kaine said. “How do we deal with this when it’s a nation we’re in partnership with?”

The US has not held any threat of real consequences so far if New Delhi doesn’t meet its demands to end the assassination campaign and punish those involved. Because the Biden administration has mollycoddled the Modi government even after credible reports of ill-treatment of religious minorities and democratic backsliding in India, New Delhi is convinced about its indispensability to Uncle Sam to counter the rise of the Chinese dragon. Put another way, the US will fight China to the last Indian, and the cavalier assassination plot has given Washington an extra handle to ensure New Delhi’s compliance.

Even if the Biden administration were to let the Modi government escape with a mild rebuke, the rest of the world, particularly countries in India’s neighbourhood and in the Western world, will be alarmed. Many will harbour second thoughts about intelligence cooperation with India once the country is perceived as a reckless global actor which violates the sovereignty of friendly countries, the rule of law and established international norms. The loss of global respect invalidates decades of effort to establish India as a responsible democratic power ready to take its place at the world’s high table. The question now would be: if India were to become Vishwaguru, what kind of great power would it be — one that follows the “rules-based global order” as it now exhorts others to do or a big bully that intimidates, threatens and targets less powerful countries?

Most democratic governments do not approve of covert killings by their operatives in friendly countries; to attempt it in the world’s most powerful country defies common sense. The payoffs must be huge to justify the risks to India’s reputation and status as a rising democratic power. None of the explanations offered so far fulfil that criterion. There is no shortage of hawks arguing that India is fully justified in eliminating Nijjar and Pannun, as they are declared terrorists who are campaigning for Khalistan among the Sikh diaspora from the safety of Western countries.

New Delhi had asked the Trudeau government in 2016 to act against Nijjar for running a terror camp in British Columbia but to little avail. In fact, Pannun, a trained lawyer, helped Nijjar draft a reply to Trudeau denying he supported violence. When the Modi government asked Interpol to issue a Red Corner notice against Pannun, he successfully petitioned the global agency to remove it last year because the information India provided didn’t comply with Interpol rules. The ministry of external affairs refuses to confirm if the Modi government ever asked the US to extradite Nijjar.

Overseas Khalistani activists like Pannun and Nijjar are annoying characters who go and petition the United Nations to recognise the killings of Sikhs in India in the 1980s as a genocide, but they have failed to revive the cause of a sovereign homeland in India for Sikhs. Khalistan is a dead horse within Punjab, a fantasy kept alive abroad by a small section of the Sikh diaspora — and now by the security establishment in New Delhi, which is flogging the dead horse when violent militancy in Punjab is long over. The state doesn’t figure in the top internal security challenges that deserve urgent attention in India. Those would be Manipur, Kashmir and Nagaland. Why was the Modi government then willing to risk its burgeoning ties with the US and the country’s international standing with such a reckless and ill-conceived plan?

Khalistan may be long dead, but the Indian security establishment continues to be dominated by officials whose professional careers were defined by that violent insurgency. Doval, who won a Kirti Chakra in 1989, is the most prominent among them. Then there was Samant Goel, a Punjab cadre IPS officer, who served for four years (with two extensions) as the head of R&AW. He finally retired on June 30,

coincidentally a date before which Gupta desperately wanted the

undercover US agent masquerading as a contract killer to assassinate Pannun.

Surprisingly, the political executive invoked the Khalistan bogey to discredit the farmers’ movement that laid siege to the national capital in 2020 against the three farm laws announced by Modi. He was forced to withdraw the laws, but the period coincided with legal and diplomatic action by his government against Kha-listan supporters abroad, which seems to have ended up now in a Manhattan court. The line bet-ween causation and correlation lies in the eyes of the beholder.

Two months ago, a retired lieutenant general witnessed a fellow retired senior army officer, a member of the RSS, “read out a list of persons who were neutralised by the Modi government to an audience of students in one of India’s most hallowed institutions”. Used to bullying and targeting critics inside India, the ruling establishment wanted to project strength and power by eliminating prominent Khalistan supporters abroad. The use of a sensitive operation for domestic political propaganda by the Modi government is the most dangerous aspect of the whole saga. Having tasted blood by using the military operations against Pakistan, however unsuccessful they may have been in achieving the stated aim, to sway the electorate, it is now willing to do the same with intelligence agencies. In pursuit of a sureshot election victory for one man, the ruling establishment is willing to hazard a strategic defeat for India.

Finally, the bumbling execution of a sensitive operation did not add to the professional reputation and standing of India’s intelligence agencies. Those who conceived these plots merely assumed they would never be caught and had not fully considered the risks they were running. Questions will be raised about the political oversight over their operations. The idea of an assassination plot inside the US and Canada was neither politically prudent nor strategically sound. The proposal should never have been approved at any level. It demonstrates the weakness of India as an “electoral autocracy”, where systemic checks and balances no longer exist, and honest feedback has been shut out. As independent institutions are continually hollowed out, more such crises are bound to emerge.

The recent contretemps are evidence of overconfidence in the country’s top hierarchy, which flows from a euphoria of power. They presume that India has arrived on the world stage. As daylight starts appearing between rhetoric and reality, their delusion has only revealed India’s vulnerabilities and weaknesses under Modi.

Singh writes on defence and strategic affairs and is currently a Lecturer at Yale University in the US