Nestled between the skyscrapers of Nariman Point, facing the Marine drive promenade, was a small, greying building. And on Saturday afternoons, a beautiful lady in a sari would enter its gates holding her son’s hand as he kicked and screamed, adamant that Tagore music wasn’t really his thing. But the lady insisted and the boy, barely seven years old, would sit through an hour of learning Tagore songs with a group of Bengali music teachers who were trying to create their own little Calcutta in Mumbai.

Somewhere between the sound of those bellowing harmoniums and my Mum revising the songs with me in the taxi home, was where it all began. Like a seed cracking open, sprouting shoots. I blame the salty Mumbai air. By the age of 10 I had certifiably developed an addiction to music, on MTV, in the local cassette store and the loop of Bollywood songs on cable. The tune that played the most was Hawa hawai sung by Kavita Krishnamurthy in the blockbuster film Mr. India.

These memories came flooding back when, 26 years later, I stood outside the gates of Kavitaji’s villa in Bangalore. With me was the BBC camera crew and we were filming the final episode of Rhythms of India — a series exploring diverse forms of Indian music. I knew my lines. The camera started rolling. And when the door opened, there she was — the voice of Hawa hawai. I must have heard it a thousand times. A giant statue of Ganesha stood in the reception of her house and even the elephant-headed God looked rather modest next to Kavitaji, who beamed with warmth as she welcomed us in. When she spotted my sarod in its case, chequered with colourful fragile stickers, I had to take the instrument out and play for her. But when my fingers touched those steel strings, there was only one melody that came pouring out, completing a 26-year-old cycle that had started in Mumbai, travelled with me to London where I spent most my life, and had returned to manifest itself in the most unexpected of ways. The melody was, of course, Hawa hawai. And Kavita ji wasted no time in joining in, relishing the sarod version of the very song that had shot her to fame in her early career.

A plant that had grown in unexpected ways

Music often does that, opening gateways that take years to close. That’s why we associate songs with people and places. They make soundtracks to our lives, both colouring our experience of the moment, while, like a photograph, capturing our own emotions and memories within it.

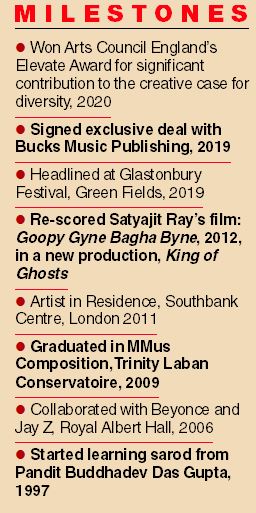

So even now, when I hear Beyonce or Jay Z playing on the radio, I’m taken back to the curved corridors of the Royal Albert Hall, London, where we stood in the wings waiting to go on stage, listening to the roar of a crowd in anticipation. A sarod is not what you’d expect to see in a mainstream, hip-hop concert. Neither is a tabla. But the Mercury award-winning tabla player Talvin Singh, who had taken me under his wing at that time, gave me a thumbs up as we stormed London’s largest stage with hip-hop royalty. And as the bass kicked in, Beyonce, flanked by dancers, embraced the spotlight, Jay Z ripped the mic off the stand and I looked around the auditorium, dazzling with camera flashes, to realise that this was the power of music — to bring worlds together, however disparate or unlikely. Looking back at it now, while Jay Z was making history, performing the first ever hip-hop concert at the Albert Hall, Talvin and I were making our own landmarks that night. We were breaking through the lines of genre, turning musical denominations on their heads and bringing ancient Indian instruments into a contemporary, global arena.

The man to have done this first was, of course, Pandit Ravi Shankar, playing at the likes of Woodstock and Madison Square Garden to a staggering audience count, introducing Americans to the love of Indian music. At a time when the Cold War threatened to consume the world, the sound of his sitar arrived as an ambassador of peace, reminding the global community that music was the only answer. In the year before he passed, I had the privilege of finally meeting with him, surrounded by his family and musical friends.

That summer, he was staying in a beautiful apartment overlooking the Thames, and I recall how witty he was, still remembering old stories, making us laugh. He was also curious and up to date with the younger generations through YouTube. But the moment that pierced most was at the end of the evening, after I had touched his feet, when he gently pressed into my chest with his finger and whispered: “Don’t forget your music, your roots.” It’s quite likely that I burst into tears at this point, overwhelmed by the magnitude of these words. And as the years went on, those roots became clearer. The seed that had cracked open in Mumbai, that had been watered by my mother’s voice singing Tagore, nourished by Bollywood, trained by classical music, egged on by electronica and hip-hop: this plant had grown in unexpected ways. And perhaps it was all those contradictions, that tangle of influences and sounds that had shaped me over the years.

Amulya Kumar in Purulia. Picture: Souvid Datta

Rehearsing with Nitin Sawhney (centre) (PIcture sourced by The Telegraph)

The climate change crisis was important to me

It was raining on the day the tangle came together. My Austrian band mate Bernhard Schimpelsberger and I were releasing our new album Circle of Sound at Southbank Centre, London, in front of a sold-out Queen Elizabeth Hall. We had layered electric pianos and overdriven bass guitars with drum-n-bass patterns and weaving through this fabric of sound was my sarod. To top it all, my dear friends Nitin Sawhney and Anoushka Shankar — pioneers of progressive Indian music in their own right — joined us as special guests. That concert and all the preparation that had led to it, taught me the value of collaboration.

Since then I’ve tried to push the limits of what that means in my own work, composing and writing music that brought communities together, fusing Korean, Japanese, soul, electronic, orchestral and Indian forces. My latest album Jangal featured Brazilian and Australian instruments. The idea was to use sounds from areas of the world that were being heavily deforested. So the title track begins with the Bombo drum, indigenous to the Amazon rainforest, which is being cleared at a disturbing and alarming rate. The track also featured an electronic version of raga Mian ki Malhar as the basis of the composition — an attempt to evoke rain clouds above those burning forests in Brazil.

The climate change crisis was important to me for other reasons too. My sarod was essentially a chunk of wood, carved out of a tree. It made me question what the carbon footprint of my sarod was. And by association, what was mine? Walking through the furious throngs in climate protests and watching the 16-year-old climate warrior Greta Thunberg demand action from the leaders of our world was deeply impactful. I felt the need to address this in the only way I knew — music. Responding to this crisis while composing Jangal was perhaps one of the few times in my life that I have experienced a complete take over — a possession by music.

I had only heard of such episodes, black-out phases when musicians would forget the world around them and be consumed by a sound, a driving ambition to create what only they could hear. But the first time I encountered it was during another film shoot. My brother Souvid Datta, now an award-winning filmmaker, and I were travelling across India meeting and documenting the lives and plight of rural musicians. The journey eventually manifested in a six-part series Tuning 2 You: Lost Musicians of India, which marked my debut as a presenter and aired on Channel 4 and Sony BBC Earth.

It was towards the end of the first episode that Souvid and I had decided to visit a man in Purulia, on the border of West Bengal and Jharkhand, a dust-smitten township surrounded by fields and broken houses. On the edge of these fields, we met Amulya Kumar – one of the doyens of a dying song form called Jhumur. His thick, silver-white hair was slicked back in the way you often see in the villages of Bengal. And his face tanned from years of toiling in the fields, crumpled into a thousand laughter lines when he smiled and offered us tea. Pulling out his dusty, relic of a harmonium, he began to sing with a haunting, leathery voice that mirrored the eroded fields around us. As we sat on his floor listening to this rare Jhumur song, I looked around the hut — not much more than a rubble of bricks and stones. Staring at the holes in his tattered ceiling I wondered what he did when it rained. He shrugged, smiled and said: “I sing… in the end there’s always music. Just music.”

These words still linger with me today. And I often think of how much power lives in these 12 little notes, that allow people all over the world, in unfortunate circumstances, living under the poverty line, to embrace pain and hardship and find a source of light in songs, rhythms and melodies.

I’d like to think that some of these moments will always live on in memory, guiding me in my search for new music, each story influencing my path forward. Most influential of all though, was the man who taught me sarod, taking me on a life-long quest to better understand this majestic instrument, and maybe through it, better understand the world beyond. This kind and generous giant of a man, my guru, Pandit Buddhadev Das Gupta will always have the largest piece of my heart as he rests in the skies now, having imparted the gift of music to me and so many of his students around the world.

The final episode of Rhythms of India will air on BBC World News on Saturday at 2.40pm