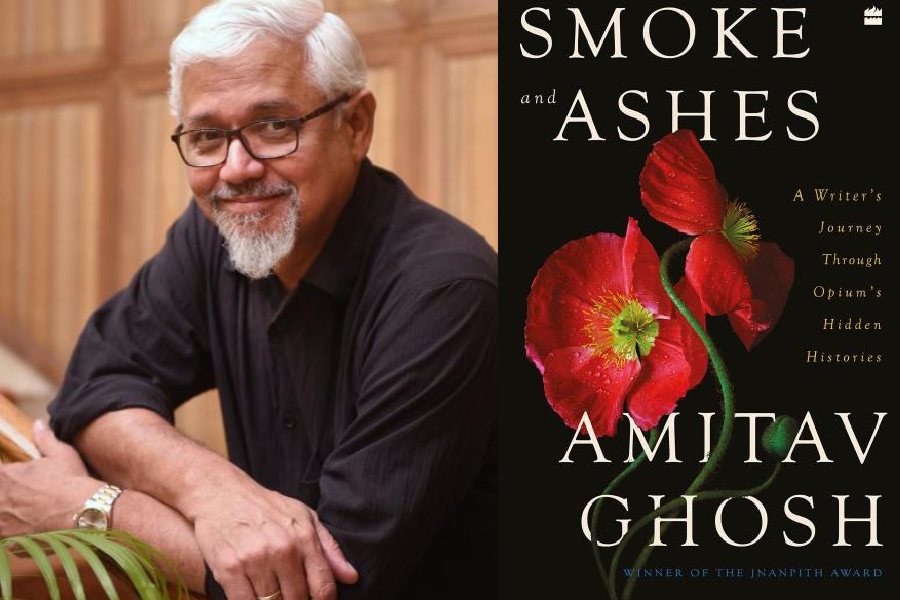

With the Ibis trilogy, Amitav Ghosh had evinced a deep interest in the story of the opium trade. In his most recent piece of non-fiction, Smoke and Ashes, which he had been ruminating on ever since he wrote The Sea of Poppies, River of Smoke and Flood of Fire, the literary rockstar’s selling point is still his ability to pirouette on a good yarn.

Smoke and Ashes is Ghosh’s rich and immersive new narrative on the fascinating opium trade — a phenomenon that straddled several centuries and continents, and connected global impulses of trade, economics, migration, resettlement, possession and power. This new project, 18 chapters long, that spans a research period of 10 years between 2005 and 2015, is an excellent pulling together of multiple ropes that anchor the rich and complex vessels that were buffeted for three centuries on the oceans that carried the opium trade.

Adeptly mining the works of leading experts in the fields of China studies, capitalism, smuggling, opium histories, colonial and postcolonial histories, the author has provided his critical readers and his loyal fans his signature style which they sailed through in the Ibis trilogy.

Ghosh shares his flight path shining three bright beams through this new project. First, he allures with his fine art of storytelling. Second, he creates an arresting ethos of material memory (his first chapter which dwells on cha, chah and cheeni and related linguistic associations with material objects). Third, he invites the reader in to share a multi-dimensional history, personal history often intersecting with national and global history (as in the telling of the innocent Chinese-origin citizens of India in Calcutta being arrested unethically during the 1962 war with China).

The interactions between polarities of race, place and language, across gender and generation, nations and peoples, castes and conventions, geographies of encounter, are still the scaffolding on which he plasters his narrative of the embattled history of the opium trade. His usual penchant for allowing his readers to find a reflection of themselves in his fiction, his accessible prose, and his sometimes self-conscious and at other times beguiling presence in the text keep him a familiar favourite for his readers.

Critical readers might point to his overwhelming reliance upon secondary sources such as published books, journal material and PhD dissertations. Thin on archival material from China and dependent on the Western archives, the project ends up presenting the story of opium from the side of the victors, the British, who defeated the weak Qing Dynasty.

In the first chapter, Here be Dragons, Ghosh states that it was not until 2004 that he thought of “visiting China for the first time”. It seems that in China he became curious about Canton, the port to where many of the ships of the opium trade plied. Then he visited China for the first time in 2005, and his first visit was to Guangzhou in Southern China, where he says he spent most of his time. But sadly for the reader, he says nothing about what he actually did in Guangzhou apart from telling us about his inferences such as when he came back to Calcutta and he drank his cup of ‘cha’, he recalled having heard the word ‘chah’ in Guangzhou, and then he looked at the cup of tea in his hand and saw that it was made of ‘china’, or chinemati (Chinese clay in Bengali).

Out of all these voluminous end notes the attentive reader could only find a few citations of where the author has used archival documents. Perhaps it is to Smoke and Ashes’s merit that it is neither an academic book nor popular history. It wedges itself somewhere in between and more. Travelogue, memoir, historical tract, all blended into a multi-textured narrative.

The material on the war is virtually exclusively from the British records and rich, as in the case of one letter on the opium trade from the British Museum, a luminous gem in the category of exciting original archival material — citation no. 80, from the Endnotes, from the chapter Pillar of Empire. Although the author does not use Chinese archives, he has consulted several books and journal articles written by specialists in China studies.

There is never just a single point of view to the complex and highly contested understanding of any history. The history of opium is no different. As perhaps Harry G. Gelberg, visiting scholar, Center for European Studies, Harvard University, who has meticulously researched the Opium Wars, argues persuasively in the working paper China as Victim? The Opium War That Wasn’t: “The 1840-42 Anglo-Chinese war (the so-called “Opium War”) is almost universally believed to have been triggered by British imperial rapacity and determination to sell more and more opium into China. That belief is mistaken. The British went to war because of Chinese military threats to defenseless British civilians, including women and children; because China refused to negotiate on terms of diplomatic equality and because China refused to open more ports than Canton to trade, not just with Britain but with everybody.” Gelberg, a scholar whose work Ghosh has acknowledged in his study, adds: “The belief about British 'guilt' came later, as part of China’s long catalogue of alleged Western 'exploitation and aggression'.”

Ghosh is generous in his acknowledgement of his liberal use of sources. “I would not have been able to write the novels, or this book, if not for the enormous body of research produced by scholars and historians: I owe them all an enormous debt of gratitude,” he admits with his characteristic charm.